For as much as I have written about warfare in the Mycenaean Bronze Age, I realized I hadn’t yet written a good overview of the subject for this website. I have written about various topics related to Mycenaean warfare, and also some lengthy articles on problematic treatments of Mycenaean warfare, including sources of disinformation and a bad YouTube video.

With this article, I will summarize what we know about warfare in the Mycenaean world. The term “Mycenaean” is used to refer to a particular culture that flourished during the Late Bronze Age. It does not, as I have pointed out before, refer to a particular people; it is an archaeological label, named after what appears to have been the most powerful centre in Greece back then, Mycenae. (Thebes may have given it a run for its money.)

Mycenaean culture

Mycenaean culture, identified by its material culture, is found on the mainland, but developed under the influence of the so-called Minoan culture – again, not an ethnic label! – on Crete. The situation is, of course, more complex than that, but this will do for now. The Late Bronze Age, referred to in mainland Greece as the “Late Helladic” period, is dated to between ca. 1725 and 1075 BC – don’t be surprised if you see somewhat different dates elsewhere; Aegean chronology is a messy business before ca. 500 BC.

Crete, as I have noted before, eventually comes within the Mycenaean sphere of influence – whatever that really means – in the fifteenth century BC, as evidenced by the introduction of Linear B for writing an early form of Greek, the introduction of new burial customs (e.g. chamber tombs), and a rectangular structure referred to as the megaron, i.e. a square central hall that opens onto a two-columned portico that forms the entrance area (e.g. at Agia Triada).

The Mycenaean era can be conveniently divided into three main phases, even if they don’t correspond perfectly with the development of weapons and armour. The first is the Early Palatial period, which covers the the final ceramic phase of Middle Helladic, as well as the Late Helladic I and II periods (down to ca. 1400 BC). Most of the evidence for this period comes from burials.

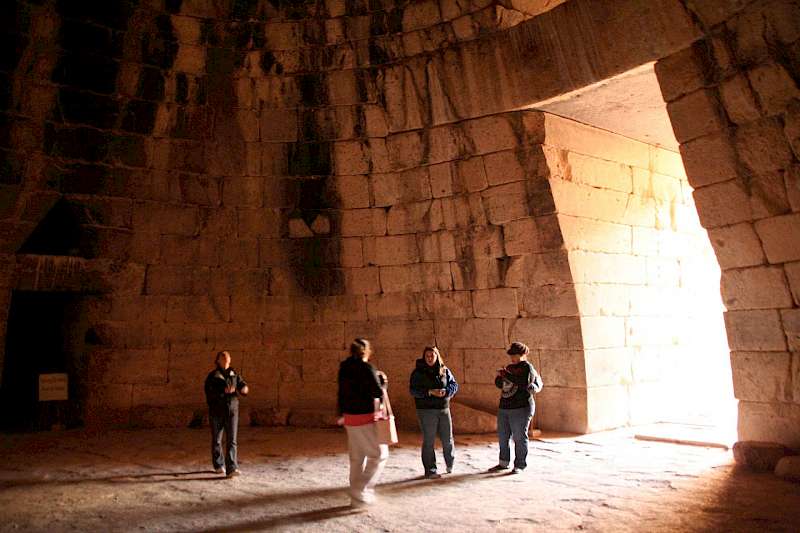

The second phase, consisting of the Late Helladic IIIA and IIIB periods, is the Palatial period, during which the Mycenaean palaces reached their zenith. In absolute terms, this period covers roughly the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BC. During this period, large-scale building projects were undertaken, such as the massive fortifications that characterize many of the centres, as well as impressive tholos or beehive tombs.

Around 1200 BC, most of the palatial centres are destroyed and – often briefly – abandoned. This is the start of the Postpalatial period, which covers the Late Helladic IIIC phase and the earliest stages of the Greek Early Iron Age. The whole of the Eastern Mediterranean was disrupted around 1200 BC, with other kingdoms, such as that of the Hittites, also crumbling as a result. I have written more about this widespread “collapse” in another article.

Developments in warfare don’t all fall neatly into these three phases, but can be roughed out as follows:

| Date | Phase | Warfare |

| ca. 1725/1700 BC | Early Palatial | Shaft Grave period |

| Mycenaean “Age of Plate” | ||

| ca. 1400 BC | Palatial | |

| Late Palatial | ||

| ca. 1200 BC | Postpalatial | Postpalatial |

This article treats the major developments in Mycenaean warfare in chronological order.

The Shaft Grave period

For the Early Palatial period, most of our information comes from tombs. Among the most informative burials of the period are the so-called Shaft Graves from Mycenae. There are two clusters of graves, one located on the citadel of Mycenae, referred to as Grave Circle A. Further away from this hill, archaeologists unearthed a second cemetery, dubbed Grave Circle B, which is slightly older than Grave Circle A.

In Grave Circle A, Shaft Graves IV and V contained the remains of five men who had been given a number of lavish grave goods. These included gold death masks, such as the so-called “Mask of Agamemnon”. The goods also included a large number of weapons, including many broken and damaged swords (that had perhaps been used during actual combat), arrowheads made of obsidian (volcanic glass), as well as more unusual weapons such as tridents and battle-axes.

The swords typically had wooden hilts that were decorated with gold discs or were entirelty gold-plated. Some swords had pommels – the knob at the top of the hilt – made of ivory or marble. The bronze blades of some weapons featured relief decorations, such as rows of horses (representing wealth?) and griffins (representing strength?).

Aside from swords, the graves also featured beautiful bronze daggers, which were often inlaid with gold, silver, and a black substance known as niello. These daggers are generally thought to have been made by Cretan craftsmen. The most famous of these is the so-called Lion Hunt Dagger from Shaft Grave IV in Grave Circle A.

The Lion Hunt Dagger depicts several men hunting lions. Two of them are equipped with a type of shield that is typical for this period, with the earliest examples known from Cretan art. This shield resembles in outline the Arabic numeral 8, and is therefore referred to as the figure-of-eight shield. It was made of wood and covered with cowhide. But we also note another type of shield, which is just as large and rectangular: it is referred to by archaeologists as the “tower shield”.

Shields like these tower shields are also known from Egypt and Southwest Asia and they appear to be a common form of protection. Most likely, these shields were adopted in Crete and were later introduced to the Greek mainland. Some scholars have proposed that the figure-of-eight shield was never a practical piece of defensive equipment. However, considering it appears in scenes that also include the – apparently perfectly realistic? – tower shield, I am not convinced of this.

The group depicted on the Lion Hunt Dagger also includes an archer. Noteworthy is that all the men are naked apart from a short kilt: they don’t wear helmets and apart from the archer, they are all fighting the lions using long thrusting spears that they are wielding with both hands. Two of the warriors are clearly shown carrying their shields across their shoulders using a shield strap, referred to in Greek as a telamon.

If the men on the Lion Hunt Dagger seem to lack protection, the same appears to be the case with the men who were interred in the graves. Breastplates made of thin sheet gold suggest that they were familiar with the concept of body-armour, but if the gold was ever fixed to leather or linen that material has long since perished.

Pieces of carved boars’ tusk were retrieved from the graves and these were almost certainly part of boars’ tusk helmets. Several examples have been unearthed on the Greek mainland and in Crete, and an especially fine example is on display at the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. A boars’ tusk helmet is also known from the Iliad, where it is described in some detail (Iliad 10.261-265). While this may be an authentic reference to something Mycenaean, it is more likely that Homer was describing an heirloom or a helmet retrieved from a looted Mycenaean grave.

A fragmentary fresco from Akrotiri, on the island of Thera (Santorini), roughly contemporary with the Shaft Graves, provides us with further information. The miniature frieze on the north wall of the West House at Thera depicts a scene of ships arriving at a coastal settlement. There are men depicted in the water that appear to be drowing. A number of men, equipped with tower shields, long lances, and boars’ tusk helmets, with the tips of their sword scabbards peaking from behind their shields, appear to be marching inland: are they supposed to be invaders or defenders?

The Akrotiri fresco suggests that larger-scale battles did happen during this period. Other objects from the Shaft Graves also provide additional insights. From Grave IV comes the so-called Siege Rhyton, which has been restored from several fragments. We see part of a town, with many different warriors scattered about. They include naked slingers and archers, as well as a figure in a tunic equipped with what looks like a boars’ tusk helmet. Many of the archers adopt a kneeling position to steady their aim: they are like snipers on the battlefield instead of loosing their arrows in volleys.

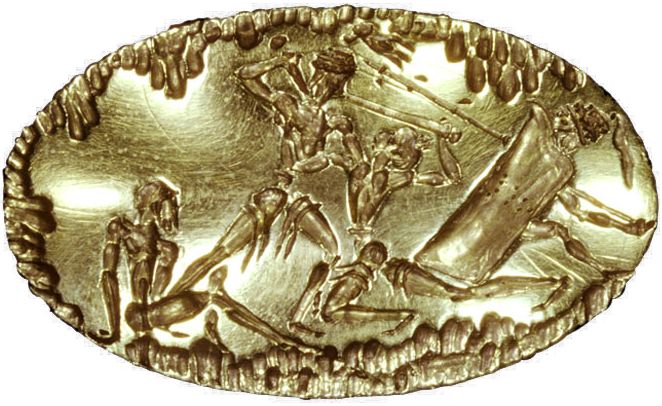

A golden ring from one of the Shaft Graves depicts what is referred to as the “Battle of the Glen”. It depicts two swordsmen locked in mortal combat, naked apart from their kilts, just like the men on the Lion Hunt Dagger. A figure on the left is seated on the ground, perhaps exhausted from the battle. At far left we see a man equipped with spear, tower shield, and boars’ tusk helmet. Does the scene commemorate a real battle of some sort or does it depict an encounter in the life of an unknown hero? Similar scenes, which are generally not too common, are known from other objects, too, such as the so-called Combat Agate from a tomb in Pylos.

Swords from this period tend to be long, sometimes even rapier-like, and the way that the hilt was fitted to the blade was often weak and prone to breakage. The earliest Mycenaean swords seem to have been adopted from those used in Crete. I wrote earlier about some blades recovered from the Minoan court complex at Malia. Over the course of the Late Bronze Age, we may note that swords tend to get shorter and sturdier, with hilts that are part of the blades themselves and therefore stronger.

In sum, the evidence we have for warfare in the Aegean during the Early Palatial period suggests that warriors, for the most part, wore little when it came to armour. This would change toward the end of this period, as I will explain in the next section. Boars’ tusk helmets are commonly depicted in art, despite obviously being an expensive piece of equipment, and they would continue in use throughout the Late Bronze Age. It cannot be excluded that helmets made of bronze were also used. For additional defence, the warriors typically relied on either their agility or on large body shields, either “figure-of-eight” shields or “tower” shields.

The Mycenaean “Age of Plate”

Archaeologist Anthony Snodgrass notes that during Late Helladic IIB, the final phase of the Early Palatial period (say, the fifteenth century BC), plate armour appears in the Aegean. This is the beginning of what Snodgrass refers to as the Mycenaean “Age of Plate”, which encompasses Late Helladic IIB and Late Helladic IIIA, so roughly 1500 to 1300 BC.

The most remarkable find from this period is an impressive bronze panoply from Dendra in the Argolid (the region in which Mycenae and Tiryns are located). It dates to early Late Helladic IIIA, or ca. 1400 BC in absolute terms. The panoply consists of fifteen separate pieces of bronze. The core consists of a breastplate and a back plate that form a cuirass that in overall shape is remarkably like the bell-shaped cuirasses that re-emerged in Greece in the late eighth century BC; there is some evidence that suggests these cuirasses were adopted during the Bronze Age in Central Europe and then reintroduced in Greece in the final stages of the Early Iron Age.

It is curious that the people of the Aegean adopted plate armour of this kind. Elsewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean, peoples like the Egyptians and the Hittites adopted scale armour. For whatever reason, the peoples of the Bronze Age Aegean never did; is a single piece of scale armour was unearthed at Mycenae that dates to the twelfth century BC and is the only known instance of scale armour to be found west of Troy.

The panoply from Dendra is the only (near-)complete suit of bronze armour that we have for the Bronze Age. Bits and pieces of similar armour have been found, such as a shoulder plate from another, slightly earlier grave at Dendra. A small stone vase recovered from Knossos and dated to Late Minoan II to IIIA, or roughly contemporary with the Dendra panoply, depicts a similar cuirass with shoulder guards. From Thebes, pieces of armour have been recovered that are again similar, but which date to the end of Late Helladic IIIA, or around 1300 BC.

It is unlikely that the person wearing this armour, which afforded protection for nearly the entire body, would ever need a shield. Indeed, the tomb at Dendra featured two swords. Some art of the Mycenaean period depicts warriors fighting with two swords or a sword and a dagger, with one blade used for parrying and the other for thrusting. We should imagine that at least some Mycenaean warriors were skilled at dual-wielding blades.

Several Linear B tablets from Knossos and Pylos feature ideograms that may represent cuirasses like the one unearthed at Dendra. There is some debate on whether or not this is correct; they could also represent horse armour or a type of metal vessel instead. But the consensus today is that the ideograms in question do depict body-armour, so that we have evidence for its use in Pylos, Knossos, and the Argolid. While apparently widespread across the Mycenaean culture region, it was no doubt used only by the wealthiest members of Mycenaean society.

With the introduction of plate armour, shields seem to have fallen out of use. Figure-of-eight shields now only appear as decorative items, either in the form of wall-paintings or as jewellery. It is possible that tower shields continued in use for a bit longer, but the evidence consists of a single pottery fragment from Tiryns that has been date to early Late Helladic IIIB (so, early in the thirteenth century BC). The evidence is slim, to say the least, and subject to misinterpretation.

Mycenaean chariots

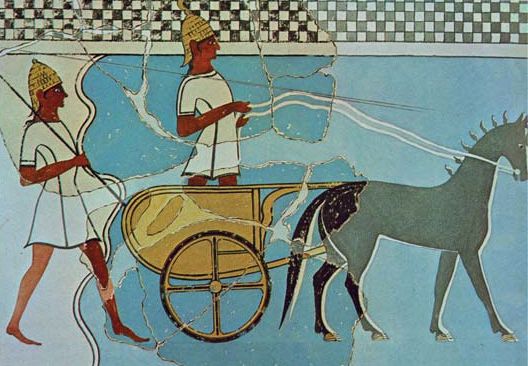

A warrior in full panoply would have been an impressive figure on a chariot. Chariots – light, two-wheeled vehicles drawn by a team of horses – were introduced to the Aegean early during the Late Bronze Age, most likely via Anatolia. Evidence for the Aegean chariot is mostly pictorial. Based on the images, Joost Crouwel, a noted expert on the subject, was able to distinguish four main types of Mycenaean chariot.

The different types of Mycenaean chariot are, in rough chronological order, the Box Chariot (characterized by a solid walled box), the Quadrant Chariot (with a box that looks like the quadrant of a circle), the Dual Chariot (a box with a curved extension at the back), and the Rail Chariot (open-walled, without extensions). Typical for the Early Palatial period are the Box and Quadrant chariots; the Dual Chariot is typical for the Palatial period, and the Rail Chariot, introduced during the late thirteenth century BC, would survive into the Early Iron Age and beyond.

Some of the grave stelae that marked the Shaft Graves at Mycenae depict chariots, apparently barrelling towards their opponents. They suggest that the Mycenaeans attacked from their chariots, perhaps using long lances, similar to how the Hittites may have used their chariot. However, the evidence is ambiguous. The fact that there is often only a single figure in the chariot, rather than a driver and a warrior, as would be typical for the ancient world, suggests that these are intended to be heroizing images.

Did people in the Aegean use the chariot as a mobile platform for archers? The few images we have of the bow being used on a chariot are all clearly depicting a hunt; the imagery may well have been borrowed directly from examples made in Southwest Asia. Furthermore, the Aegean landscape is simply unsuitable for deploying chariots in this fasion, comparable to what we know of, for example, Bronze Age Egypt. There is simply not enough space for chariot manoeuvres, and the terrain is also quite rough and not exactly well suited for chariotry.

For the Palatial period, we have some written evidence in the form of Linear B inscriptions on clay tablets. These suggest that the Mycenaean palaces were able to field chariots that numbered in the hundreds. Tablets from Knossos suggest a fleet as large as perhaps 400 vehicles. Still, this is small stuff when compared to Egypt and the Kingdom of the Hittites, who were able to field thousands of chariots during the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC). Of course, those kingdoms themselves were far bigger than anything we find in the Aegean.

The evidence for the military use of the chariot is in any regard slim. They are depicted in Mycenaean wall-paintings, but never in the context of battle. What we do see is that chariots are fairly consistent associated with a driver and a spearman. This image persists also after the collapse of the Mycenaean palaces, and it seems most likely, as Crouwel has also argued at length, that the Mycenaean chariot was used a “mode of conveyance”. In other words, chariots were used to deliver spearmen to the battlefield, and were not themselves deployed in battle.

The heyday of the Mycenaean palaces

At some point during the fourteenth century BC, Knossos on Crete, which may have served as a kind of capital city for the entire island, is destroyed. The exact date of the destruction is a matter of contention, but by 1300 BC, Knossos is no longer a major player within the Eastern Mediterranean. The destruction, perhaps at the hand of jealous princes from the mainland, meant a severe disruption in the circulation of bronze. Large objects made of bronze mostly disappear from the archaeological record, including armour.

At the same time, the Mycenaean centres in mainland Greece, such as Mycenae, Thebes, and Pylos, appear to reach their zenith. Mycenaeans exert ever more control across the Aegean islands and Anatolia, where they were also in contact with the Hittites. There is evidence for a Mycenaean presence in, for example, Milawatta (the city later known as Miletus).

Archaeologists have, until relatively recently, mostly focused their investigations on the Mycenaean palaces. Most of the palaces, such as at Mycenae and Tiryns, occupy fortified hilltops. They were citadels. But Mycenaean cities like Mycenae itself were larger than just the citadel: each also possessed an extensive lower town. These lower towns, at Mycenae, Tiryns, and other places, have attracted far less attention, but they may reveal much about the way that ordinary people lived during the Late Bronze Age. Some centres seem to lack fortifications entirely: it’s still not entirely clear if Pylos, for example, had walls.

The largest building projects of the Mycenaean era date to the thirteenth century BC, including many walls that remain visible even today. The stone blocks used in their construction are so massive that Greeks of the historic era believed they had been the work of Cyclopes (e.g. Pausanias 2.16.5 and 2.25.8). Mycenaean fortifications lack towers, though they may have projecting walls. They seem to have lacked crenellations; most likely, the tops of the walls were intended to be fighting platforms from which to launch projectiles at attackers.

The fortifications of Mycenae were expanded and came to include the Shaft Graves from Grave Circle A, perhaps because the people buried there were venerated as ancestors. The famous Lion Gate at Mycenae, a monumental entrance to the citadel, dates from around 1250 BC. Within the citadel of Mycenae, we find several streets and a complex of buildings, including houses and workshops. During the Bronze Age, most structures had flat roofs.

A road leads the visitor from the Lion Gate up to the palace. The core of each Mycenaean palace is remarkably standardized: it consists of a structure referred to as a megaron: a square central hall that opens onto a two-columned portico that forms the entrance area. This basic structure persisted in Greece for centuries and eventually formed the basis of the Classical Greek stone temple. In Mycenaean times, the central hall featured a large round hearth surrounded by four pillars that supported a roof; the megaron likely had an upper story.

During the Mycenaean era, people didn’t practice cremation. Instead, corpses were buried as they were. Typical of the Mycenaean era are rock-cut chamber tombs, which consist of a passageway (dromos) leading to a central chamber (thalamos). More elaborate tombs are the tholos or “beehive” tombs, which must have required large amounts of manpower to build. They feature a dromos like the chamber tombs, but the burial chamber itself has a circular plan and is built up using large stone blocks and has a corbelled ceiling. Tholos tombs were also dug into the soft earth of a hillside rather than into rock.

Especially for the thirteenth century BC, the wall-paintings that decorated the walls of the Mycenaean palaces provide a wealth of information. They include hunting scenes, in which men with throwing spears (javelins) hunt deer and boar. The figures in these scenes have bare heads and wear tunics; their lower legs are often wrapped in linen. Sometimes, a single greave is worn as well, which C.D. Fortenberry (1991) suggests was an indication of rank.

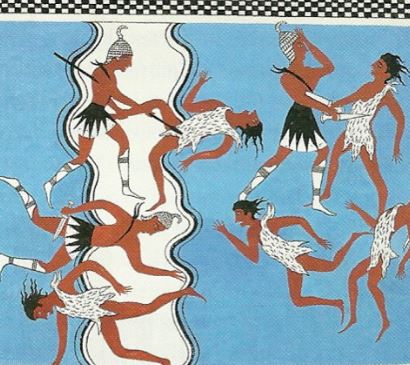

Some Mycenaean wall-paintings depict scenes related to warfare. The so-called “Tarzan” fresco from Pylos depicts a battle in what is perhaps to be interpreted as a river between two groups of warriors. One group consists of warriors equipped with kilts, boars’ tusk helmets, and linen wrapped around their lower legs, often with one shin protected by a greave. The are uniformly equipped, suggesting that they belong to the palace. Their opponents wear animal skins and have tangled hair: they are intended to be “savages” from beyond the territory ruled by Pylos’ ruler. One of the soldiers wields a spear; the others are armed with swords. Interestingly, both sides suffer losses in the battle.

Another fresco from Pylos depicts a similar battle at the river, which perhaps marks the border of Pylian territory. This time, all the men wear loin cloths or short kilts; some have boars’ tusk helmets, while others have the same ruffled hair as the savages from the earlier fresco. In the fragments that were used to piece the painting back together, all the combatants fight using swords. If you compare the blades used in these frescoes with those from the objects we examined earlier, you’ll notice that they have generally become shorter and stouter.

By the end of the thirteenth century BC, a new type of sword is introduced from Central Europe. This Naue II-type sword is ideally suited for both cutting and thrusting. It would quickly spread throughout the Aegean and become the most popular type of sword. When the Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age, this sword continued in use, translated from bronze to iron. It would remain in use until the sixth century BC, when it was replaced by a shorter sword with straight cross-guard.

The Linear B tablets created by the palaces give some information regarding military organization. They suggest that the palaces produced and maintained at least some of the military equipment, such as arrowheads, swords, spears, arrows and javelins, helmets, and chariots. However, the palaces did not apparently provide all the necessary equipment, as there are many tablets in which incomplete chariots are provided. It could well be that rank-and-file soldiers were equipped by the palaces or by their commanders, and that the palace provided wealthy combatants only with part of the equipment they needed. Quite possibly, armies were raised using a mixture of private and public (“palatial”) means (see also the overview in O’Brien 2013, pp. 29-30).

The texts also offer us a clearer picture of the structure of Mycenaean society. At the very top stood the wanax, a term usually translated as “king”. We also find chiefs of various kinds that are referred to using the term qa-si-re-u, from which the later Greek word basileus is derived. In later times, the word means “king” or “prince”, but in the Mycenaean context it apparently refers to different kinds of lower-level leaders, such as heads of guilds.

Directly beneath the Mycenaean wanax was a lawagetas. The word probably means “leader of the people”. He may have been expected to lead the army. The contemporary Hittites often had the crown prince put in command of the armies: perhaps the Mycenaean lawagetas was similar? We also find heqetai or “followers”. In the Linear B tablets, these men are associated with chariots and horses, and they are therefore likely members of the Mycenaean elite. The tablets also list large numbers of specialist craftsmen, farmers, and slaves.

Before we leave the Palatial period behind us, a minor note on the use of cavalry. Cavalry proper is a feature of the first millennium BC, but there is some evidence that horses were sometimes ridden before the end of the Bronze Age. A Mycenaean sherd, dated to the Late Helladic IIIB period, from a tomb near ancient Ugarit in northern Syria depicts a horsemen equipped with a sword. A terracotta figurine of a rider, dated more specifically to Late Helladic IIIB1, has been unearthed at Mycenae. Similar riders are known from Egypt: these horsemen served as dispatch riders and mounted scouts; they are unlikely to have fought from horseback.

Warfare during the Postpalatial period

Nothing lasts forever and the Mycenaean palaces were destroyed around 1200 BC. The reasons for this destruction are likely to be due to a number of reasons, including perhaps massive earthquakes, droughts, and famines, that may have caused uprisings or other forms of unrest (but the “Dorians” were not to blame!). Elsewhere in the Eastern Meditteranean, too, we find evidence of destruction and disruption. The Syrian city of Ugarit is destroyed; the Hittite Kingdom collapses.

Some of the palaces were only briefly abandoned and then re-occupied, as was the case with Mycenae itself. Indeed, Mycenae would continue to be inhabited down to the fifth century BC, when it was sacked by Argos, and part of the Mycenaean fortifications, which had continued in use, destroyed. But even then, Mycenae was re-occupied, with a tower added to the citadel during Hellenistic times. Especially in Crete, we see that a lot of settlements near or on the coasts are abandoned in favour of places located in higher, more easily defended locations.

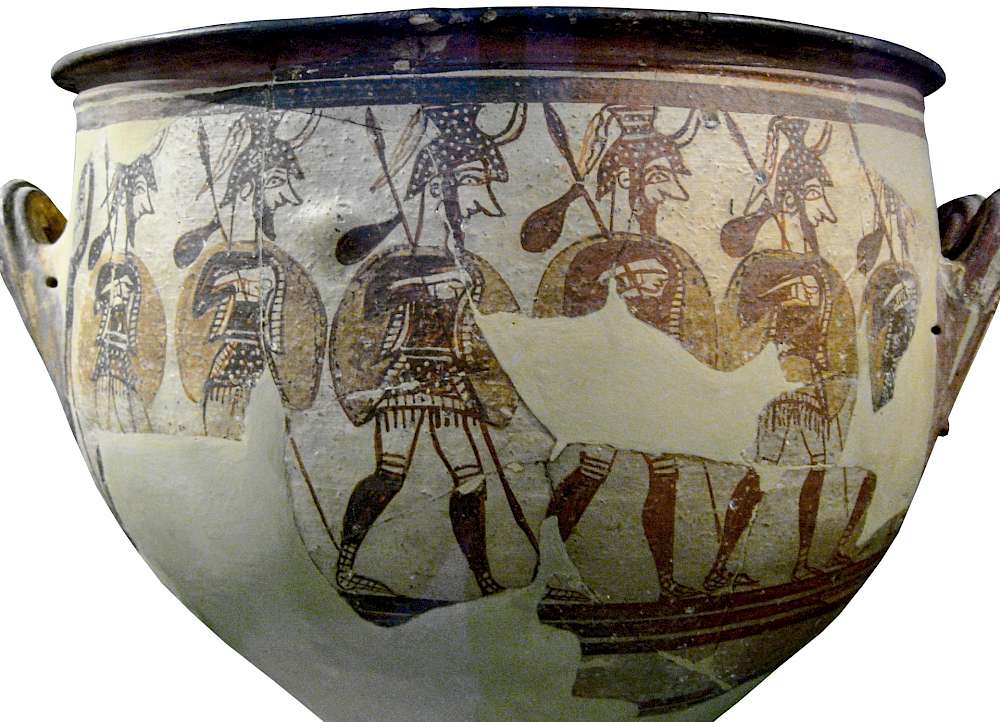

The evidence for warfare during this Postpalatial period is limited to finds of weapons from graves and figurative scenes on generally large pots of the Late Helladic IIIC period (ca. the twelfth century BC), the final phase of the Bronze Age proper. As Matthew Lloyd has pointed out, “the rise in violent iconography and the prestige of swords and spears in the Postpalatial period is no coincidence, and that willingness to do violence was becoming a necessary skill in the cultural climate.”

An example of Late Helladic IIIC pottery is the “Warrior Vase” from Mycenae. It is a large vessel used to mix water and wine. Both sides depict warriors. On one side, the men have raised their spears and are preparing to attack; on the other, warriors march away with little knapsacks tied to their spears, which they hold aslope against their shoulders. They are wearing helmets of some kind, leg protection, and perhaps also a kind of corslet. Most notably, they are also equipped with shields. The warriors that are marching away have crescent-shaped shields.

Battle-scenes from other vases and pottery fragments show that the spear is the most used weapon. It is often brandished overhead and perhaps it was apparently used as a throwing weapon. Other warriors wield swords; we also find archers. In addition to the crescent-shaped shields of the Warrior Vase, we also find square shields and oblong shields with scallops cut from the sides, which resemble Hittite shields and the later, so-called Dipylon shields found in Late Geometric figured scenes of the late eighth century BC.

Aside from differences with the preceding period, we may also note some continuity. The rail chariot, introduced during the late thirteenth century BC, continues in use. Likewise, many scenes of battle that date from the twelfth century BC feature ships that are similar to warships of the Palatial era, with a flat keel. These vessels would continue in use until the Archaic period, undergoing relatively minor changes, including being fitted with a bronze ram.

Closing remarks

Observant readers may have noticed that I have not once referred to the Homeric epics or the story of the Trojan War in this article. This was intentional, because even if the story of the Trojan War has roots that stretch back to the Late Bronze Age, there is (almost) nothing in the epics that can be positively identified as Mycenaean.

However, there are traces of a (possible) Trojan War to be found in Anatolian sources that do go back to the Bronze Age. It is beyond the remit of this article to devote too much space to the subject here, but interested readers should check out Mary R. Bachvarova’s From Hittite to Homer. The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic (2016).

For example, Bachvarova notes (p. 400-401):

We know that the story tradition about Troy is indeed very old. As mentioned in earlier chapters, the destruction of Troy/Tarwiza may have already reached legendary status among the Hittites in the Late Bronze Age, and Luwians were already singing about “steep Wilusa” in the fourteenth century BCE. There is, however, no reason to believe that a Mycenaean epic about the fall of Troy existed.

But I hope that this article demonstrates that Mycenaean warfare is interesting in and of itself; it does not have to be given meaning by reference to the story of the Trojan War, or by forcing the Homeric epics to somehow fit into the Late Bronze Age. Archaeology has unearthed a great deal about the Mycenaean world without us having to take recourse to texts that were first written down centuries after the end of the Bronze Age.

Furthermore, I hope that this diachronic overview has given some idea of how dynamic warfare was for the period under examination. Weapons, armour, and related items changed continuously over the course of the Late Bronze Age, and I have only touched on major developments here.

Further reading

- Josho Brouwers, Henchmen of Ares. Warriors and Warfare in Early Greece (2013).

- Hans-Günter Buchholz and Joseph Wiesner, Kriegswesen, Teil 1: Schutzwaffen und Wehrbauten. Part 1E1 of the series Archaeologia Homerica (1977).

- Hans-Günter Buchholz, Kriegswesen, Teil 2: Angriffswaffen. Part 1E2 of the series Archaeologia Homerica (1980).

- Hans-Günter Buchholz, Kriegswesen, Teil 3. Part 1E3 of the series Archaeologia Homerica (2010).

- Joost Crouwel, Chariots and Other Means of Land Transport in Bronze Age Greece (1981).

- Oliver Dickinson, “What conclusions might be drawn from the archaeology of Mycenaean civilisation about political structure in the Aegean?”, in: Jorrit M. Kelder & Willemijn J.I. Waal (eds.), From LUGAL.GAL to wanax. Kingship and Political Organization in the Late Bronze Age Aegean (2019), pp. 31-48.

- Tim Everson, Warfare in Ancient Greec. Arms and Armour from the Heroes of Homer to Alexander the Great (2004).

- Nic Fields, Bronze Age War Chariots (2006).

- Cheryl Diane Fortenberry, Elements of Mycenaean Warfare (unpublished PhD thesis, Cincinnati; 1990).

- Cheryl Diane Fortenberry, “Single greaves in the Late Helladic period”, American Journal of Archaeology 95 (1991), pp. 623-627.

- Elizabeth French, Mycenae: Agamemnon’s Capital (2002).

- Nicolas Grguric, The Mycenaeans, c. 1650–1100 BC (2005).

- Katherine M. Harrell, Myceaean Ways of War. The Past, Politics, and Personhood (unpublished PhD thesis, Sheffield; 2009).

- Guy Middleton, The Collapse of Palatial Society in LBA Greece and the Postpalatial Period (2010).

- Krysztof Nowicki, Defensible Sites in Crete c. 1200-800 BC (LM IIIB/IIIC Through Early Geometric) (2000).

- Stephen O’Brien, “The development of warfare and society in ‘Mycenaean’ Greece”, in: Stephen O’Brien and Daniel Boatright (eds), Warfare and Society in the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean: Papers arising from a colloquium held at the University of Liverpool, 13th June 2008 (2013), pp. 25-42.

- Louise Schofield, The Mycenaeans (2007).

- Anthony Snodgrass, Arms and Armour of the Greeks (1967; new material, 1999).

- Bernhard Friedrich Steinmann, Die Waffengräber der ägäischen Bronzezeit. Waffenbeigaben, soziale Selbstdarstellung und Adelsethos in der minoisch-mykenischen Kultur (2012).

- Piotr Taracha, “Warriors of the Mycenaean ‘Age of Plate’”, in: Barry Molloy (ed.), The Cutting Edge. Studies in Ancient and Medieval Combat (2007), pp. 144-152.

- Shelley Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant (1998).