In a rather odd quirk of linguistic happenstance, the English language uses the ancient Greek word for “tattoo”, but not to denote an actual tattoo. Tattoo is a Polynesian loan word, from tatau (to mark). In ancient Greek, the word for tattoo was stigma, giving us the word… stigma, obviously. Yet, when we consider the historical and cultural legacy of tattooing within Europe, stigma is a very appropriate word indeed.

So why is it that English uses the Greek word for tattoo as a term to describe a mark of disgrace or a collective feeling of disapproval toward something? Perhaps it can be explained in some way when we consider the ancient Greek perception of tattoos, and indeed, how they used tattoos themselves.

Tattoos in war

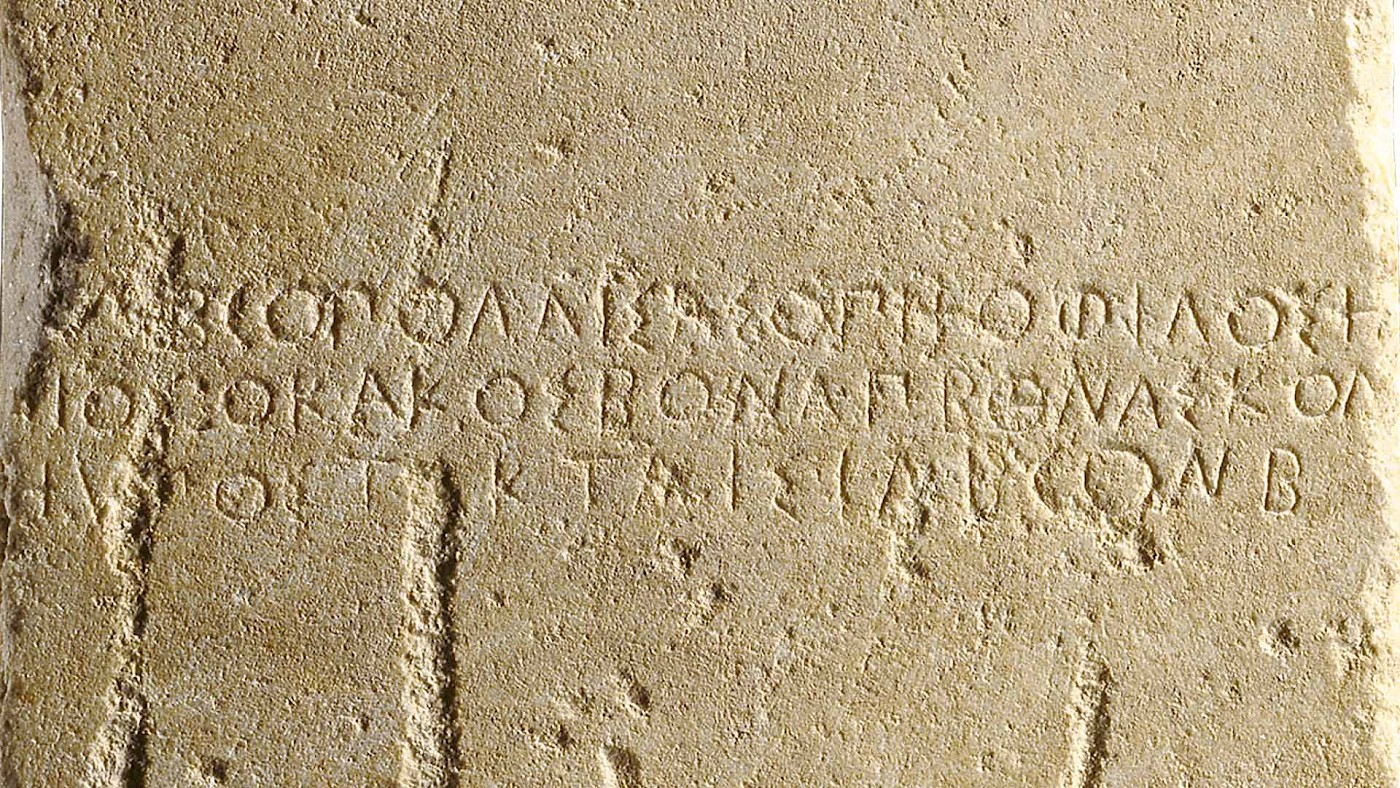

For the Greeks, to receive a tattoo during war was a mark of failure, of cowardice, and of defeat. One of our earliest dated pieces of evidence for this comes from a small funeral inscription dedicated to an otherwise unknown man named Pollis of Megara, approximately 480 BCE:

I speak, I, Pollis the dear son of Asopichos,

Not being a coward, I for one died

at the hands of the tattooers.

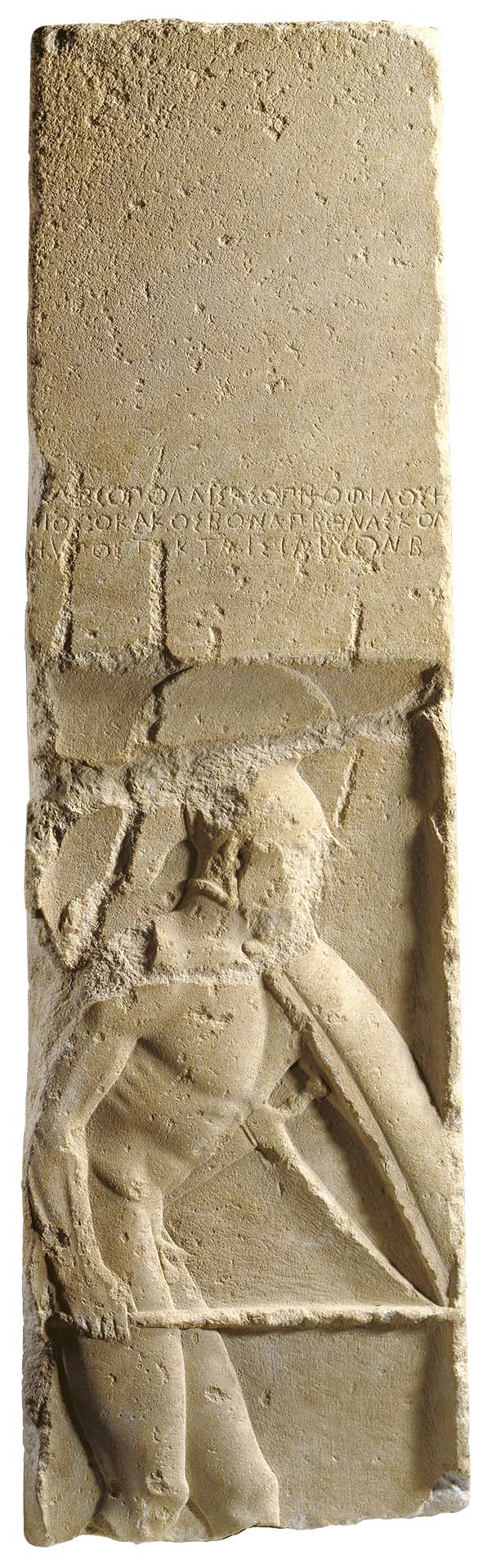

This inscription sits atop a dynamic relief image of a Greek hoplite, armed with his iconic round shield and holding the shaft of his spear. The iconography aligns with the inscription to project a clear masculine ideal. One that connects his military service, his death in war, and his innate bravery, with his resistance to being tattooed.

Whether it is actually true that Pollis died without being tattooed as a prisoner of war, is not actually important. For Pollis – or more likely his family, who would have commissioned the piece – only a coward would submit to being given the slavish mark of a tattoo: a “real” Greek man would rather die.

The identity of Pollis’ feared tattooers is not clear. Originally, scholars had assumed that this referred to the Thracians, a people that were often stereotyped by the Greeks as being tattooed. However, the dating of the inscription combines with further ethnographic information given by sources such as Herodotus to suggest a more likely candidate would be the Persians.

There is evidence to suggest that the Persians did tattoo some prisoners of war. Following the failed Greek stand at Thermopylae in 480 BCE, and the death of the Spartan commander Leonidas I, the few predominantly Theban survivors surrendered and were taken to the Great King, Xerxes I. As punishment for their resistance, Xerxes had a number of them executed. According to Herodotus, those who were left alive were to be tattooed with the royal marks (7.233.2).

While the Greeks abhorred these tattoos, and the threat of them, this did not stop them from using them in a similar manner. During the Athenian subjugation of Samos in 440-439 BCE, both sides were alleged to have tattooed their prisoners on the forehead with their own distinctive marks. The Samians used a particular type of ship called the samaina, while the Athenians used the mark of an owl (Plutarch, Pericles 24-8; Aelian VH 2.9).

The style of these tattoos, and the number of times they must have been used, suggests a preset design like a stamp or brand was used rather than an individual tattoo created each and every time. We see a similar practice, according to Plutarch, with the Athenian captives on Syracuse following the failed Sicilian Expedition of 415-412 BCE (Nicias 29.1). The prisoners were tattooed with horses, the symbol of their Syracusan captors.

The position of the tattoos is revealing as the forehead is a difficult place to cover up and hide, while the choice of imagery imitated the stamp of each polis’ respective coinage. As Geoffrey Bakewell argues, the act simultaneously marks the men as both property of the state and also converts them into currency for the market.

Tattoos and enslavement

The market, of course, refers here to the slave market, and if there is one continuous ideology assigned to the tattoo in Greek culture, it is one of enslavement.

Not all enslaved people were given tattoos. A tattoo marked out someone as being different, and that difference was rarely a positive thing. War captives were marked, as mentioned, highlighting their apparent cowardice in battle and their failure to avoid capture.

Other enslaved people were given tattoos for running away, or more generally disobeying their enslavers. Most of our evidence for this comes from Athenian comedy, which is perhaps revealing in itself. Athenians derived great humour from watching fictional slaves being threatened with, or indeed describing their tattoo punishments.

In Wasps, the enslaved Xanthias cries out wishing he had a tortoise shell to protect him from his enslaver’s stick. His words ring out: “I am being tattooed to death with a stick” (Ar. Wasps 1296). In Frogs, the god of the underworld Pluto threatens to treat petty politicians as if they were disobedient slaves; subjecting them to tattoos and chains (Ar. Frogs 1508-14). Or in Birds, where the topsy-turvy utopia known as Cloud Cuckoo Land promised to accept what was once ugly as now being beautiful, turning the tattooed runaway slave into a beautiful spotted bird (Ar. Birds 760-1).

While we are not exactly certain what was tattooed on the heads and faces of enslaved people, one scholion to Aeschines suggests that they were written on with the words: “Stop me, I am running away.”

To the Greeks, the very act of tattooing another person confirmed your control over them. In essence, a tattoo signified your lack of personal autonomy and therefore your freedom. Nowhere is this clearer than in Herodotus’ account of the outbreak of the Ionian Revolt in 499 BCE.

The Greek ruler Histaeus intended to incite his nephew Aristagoras to revolt against Persian rule. To send a message that would evade Persian capture, Histaeus tattooed his letter onto the head of an enslaved man and waited for his hair to grow before he was dispatched. With the tattoo fully covered, the man made it to Aristagoras without raising suspicion who promptly shaved his head and read the message.

This episode is often mentioned in the history books as an ingenious ploy by the Greeks, but as Page Du Bois points out, this story reinforces the relationship between tattoos and enslavement (2003, pp. 106-9).

Tattoo removal

In a society in which you did not choose to have tattoos, it comes as little surprise that there should be a thriving business in tattoo removal. One inscribed miracle at the healing cult of Asclepius at Epidaurus describes the visit of a Thessalian man named Pandarus (IG IV2 I 121, 48–54).

Pandarus came to the site to have a tattoo removed from his head. While there, he received a vision from Asclepius, where the healer wrapped Pandarus’ head with a bandage and ordered him to remove it once he had left the sanctuary. Following these instructions, when Pandarus removed the bandage, the letters had transferred themselves from his skin and onto the fabric.

The inscription goes on to describe a swindler named Echedoros, whom Pandarus had given money to dedicate at the shrine on his behalf but he kept for himself. Asclepius visited him in a vision and wrapped the bandage around his head. When Echedoros removed the bandage, he found that the tattoo of Pandarus had now been transferred to his own forehead.

Ignoring the miraculous nature of this story for a moment, the presence of the bandage is interesting because it offers similarities with a much later Greek treatment for removing tattoos. The medical author Aetius, writing in the fifth/sixth century CE, describes two possible prescriptions to help remove tattoos: using either lime or gypsum with sodium carbonate, or a mixture of pepper with rue and honey.

One of these would be applied to a cleaned tattoo, which should have already been bandaged for 5 days prior. Before application, the tattoo was pricked with a needle, cleaned again, and rubbed with salt. Once the prescription was applied, the tattoo was bandaged for a further 5 days. On day 6, the tattoo was rubbed once more with the prescription. For a full tattoo removal, Aetius says that this entire process would take roughly 20 days and could be done without any major ulcerations or any scarring.

Not everyone was willing, or indeed able, to undergo this kind of treatment. So, a more practical solution where possible was to simply grow your hair so that the tattoo was no longer visible, or simply to wear a bandage and hope that no one asks (Athen. 225a–b, Porph. V. Py. 15).

Conclusion

When explored in isolation, it is clear what the Greeks thought of tattoos. To mark the body of another person was a clear sign of degradation and servility. The clear desire to avoid receiving a tattoo and the business of tattoo removal highlights the hatred and disdain with which tattoos were held in Greek society. A tattoo was a stigma, in both the ancient and modern sense of the word.

However, the Greeks were not just aware of their own tattooing culture. As Greek writers began to consider other societies and cultures around them, they came into contact with very different relationships with tattoos. This exposure dramatically changed the way the Greeks talked about tattoos, even if it did not change the way they perceived their own. In part 2, we will explore the Greek’s understanding of these other tattoo cultures.

Further reading

- Geoffrey Bakewell, “Agamemnon 437: Chrysamoibos Ares, Athens and Empire”, Journal of Hellenic Studies 127 (2007), pp. 123-132.

- Page Du Bois, Slaves and Other Objects (2003).

- Christopher P. Jones, “Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity”, Journal of Roman Studies 77 (1987), pp. 139-155.

- Christopher P. Jones, “Stigma and Tattoo”, in: J. Caplan (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History (2000).

- Deborah Kamen “A Corpus of Inscriptions: Representing Slave Marks in Antiquity”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 55 (2010), pp. 95-110

- Owen Rees, “Incompatible Inking Ideologies in the Ancient Greek World”, in: S. Kloß (ed.), Tattoo(ed) Histories: Transcultural Perspectives on the Aesthetics, Narratives and Practices of Tattoo (2019), pp. 277-294.