When I was a first-year BA student, I was taught that archaeology is like a crime scene investigation: you find clues and traces and formulate the most plausible hypothesis. I find that this is a telling similitude, because it shows what archaeology really is; we find objects from the past and we use these to reconstruct how people in that time lived.

A problem is that we are often not sure exactly how objects were used. We can look at them from different perspectives and need to decide which ones are likely to be correct. How we make these interpretive decisions depends on the methodology used.

Analysing this evidence in different ways can lead to different reconstructed pasts. This is not to say that we can never know for sure what the past was really like. On the contrary, combining and comparing different methodologies, different ways of looking at the remains of the past, can point the way to a plausible reconstruction.

Nevertheless, we have to be ready to adjust this reconstruction when new data, or indeed a new methodology, make it not so plausible anymore. This doesn’t just apply to archaeological remains, but also to documents. These, too, are only a part of what people in the past have produced and which belong to a society that is distant to us in time (and often also space). Hence, we miss out on a lot of aspects that were implicitly understood by our ancestors, but are foreign to us, such as certain power dynamics and customs.

These issues become even more acute when we study historical periods and places for which the evidence, both literary and material, is limited.

The Second Intermediate Period

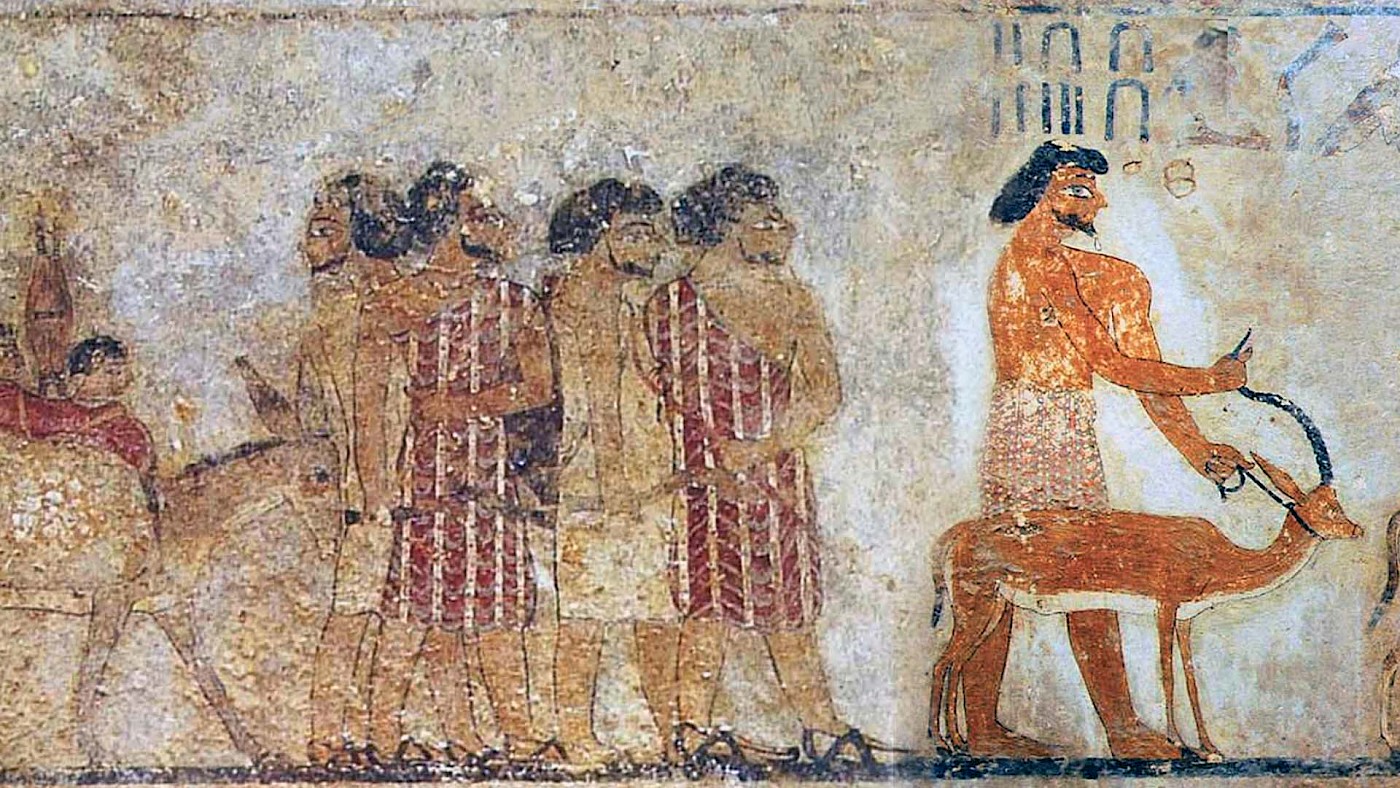

I experienced many of the aforementioned issues first-hand, studying the Second Intermediate Period in Egypt (ca. 1775-1550 BC). This period follows the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2050-1775 BC), and is characterized by ancient Egypt being divided politically and culturally. A dynasty of foreign, i.e. Levantine origins, known as Hyksos, ruled in the northern part of Egypt and possibly exerted an influence in the south, even though for a very short period.

Very few written documents remain for this period, and the material finds were first analysed as much as a century or more ago. Back then, scholars were not very interested in this period, and the questions they asked of the material were very different from the kinds of questions we seek to ask today, and their methods were very different, too.

This has resulted in much data being lost, such as the exact archaeological context, the material, or even the shape of part of the objects that have been unearthed. Many objects were also misdated.

These problems, combined with a relatively uncritical analysis of written texts, has led early scholars to view the Second Intermediate Period as kind of a dark age, with the Hyksos cast into the role of invaders who swept into Egypt and brought a period of general decline, with different regions in Egypt becoming isolated.

This interpretation has been disproven by modern research, which has demonstrated that this was not a period of “decline”, and that the Hyksos were not invaders, but emerged from the Levantine population that was already living in Egypt and who managed to exploit the power vacuum that emerged as the result of a weakening ruling dynasty.

In my PhD thesis, I used network analysis to demonstrate what kind of contacts still existed between different areas in Egypt, and how these developed over time. The idea that many areas were completely isolated from each other has been shown to be false, even though the contacts between different areas tended to be less intense than was the case during the Middle Kingdom.

Network analysis

Network analysis was born in the social sciences – it is indeed commonly known as Social Network Analysis – and has recently been introduced in archaeology. While it has found its way in the archaeology of the ancient Aegean, prehistoric and medieval Europe, and the pre-Hispanic Americas, it has never been used before to analyse Egyptian material culture. Network analysis is conducted using special applications, where you input the data, perform mathematical calculations, and generate diagrams and maps.

Network analysis is useful in detecting different types of relationships between data sets. In the social sciences, these mostly involve people, or groups of people, which we know to share something, like attending the same gym or the same school, or going to the same event.

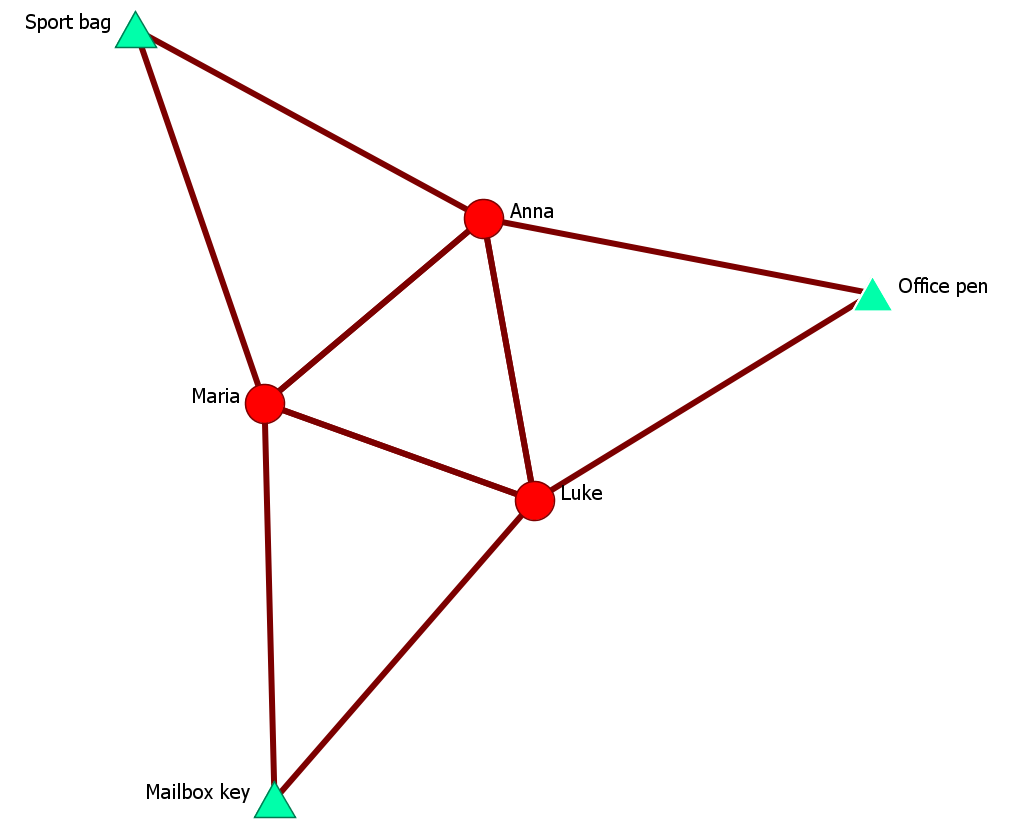

For example, if we know that Anna and Maria go to the same zumba class, that Anna and Luke work in the same office, and that Maria and Luke live in the same condo, these relationships would create the diagram depicted below, where all are connected in the same way and each share one element.

When dealing with material culture, there is one big difference when it comes to analysis. While in the previous example we start from the individuals and their relationships, in archaeological analysis we start from the material remains left from these relationships. As a result, we are taking a step back.

Let’s return to the previous example. Imagine archaeologists have found a number of items that belonged to these people. In one house (e.g. Anna’s), archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a recognizable pen and a sports bag. In another house (e.g. Maria’s), archaeologists have found the remains of a similar sports bag, as well as a mailbox key. Then, finally, in yet another house (e.g. Luke’s), archaeologists have unearthed another pen similar to the one found in Anna’s house, as well as a mailbox key, similar to what was found in Maria’s house. The latter two dwellings (Maria’s and Luke’s houses) are also found close together, let’s say they are part of the remains of an apartment building.

You can suppose that these different types of objects – the pens, the sports bags, and the mailbox keys – all look alike because the aforementioned people were using the same gym, worked at the same office, or lived in the same building. But this is all circumstantial: the similarity could be due to other factors, i.e. two different gyms using the same brand for the sports bags they give out to clients. If you are lucky, you could find some writing or a logo or a trademark on the objects, showing that the objects came from the same gym or the same office.

Nevertheless, even in that case you cannot rule out other possibilities: i.e. a gym having more premises, or the same company having multiple offices. In the case of the mailbox key, the fact that they were found together suggests that these people lived in the same building.

Thus, when dealing with material culture the reconstruction of the relationships and the use of network analysis is more indirect, and direct relationships cannot be postulated a priori without further evidence. At most, we can talk about a range of similarities, which suggest a similar environment: Anna and Maria probably went to the same gym, but they may well have gone to different classes or visited different locations owned and operated by the same chain. It doesn’t automatically follow that they would have known each other.

When written texts are available, the situation is not always made easier. For example, some people could be referred to only by their title or a nickname, thus we don’t know precisely who they are. There could also be homonyms, or other factors could come into play. Going back to the previous example, imagine that Maria uses her original surname on her gym card, but on the key card she uses the name of her spouse. We could not be sure that we are talking about the same Maria, unless we have other proof that she is the same person (e.g. a marriage certificate).

Closing thoughts

Network analysis is not some kind of magic mixer where we put fruit in and always get the same juice: the juice we get depends on the fruit that we use. In the same way, the graphs that are generated as part of network analysis depend a lot on the data we decide to include and on other small – but not trivial! – decisions.

I will write about these issues in future articles, and how it is possible to make the most out of network analysis, even when the data are more limited, as is the case with the Second Intermediate Period.