Homer provides, as always, a convenient starting point. The Greeks frequently entertain themselves by engaging in sports and games. Funeral games in particular combine funerary rites, religion, and athletic pursuits with displays of martial prowess, even though we know that such games could also be organized during religious festivals or as a way simply to kill time. Some of the prizes that could be won in these contests included gifts of armour and weapons.

Games for Patroclus

The funeral games organized in honour of Patroclus include a number of sports with a distinctly military flavour. The Greek engage in both archery and javelin contests (Il. 23.850 and 23.622), but the games also included a foot race. The latter offers a chance for Achilles to show the Greeks that he is the fastest runner among them (Il. 23.792).

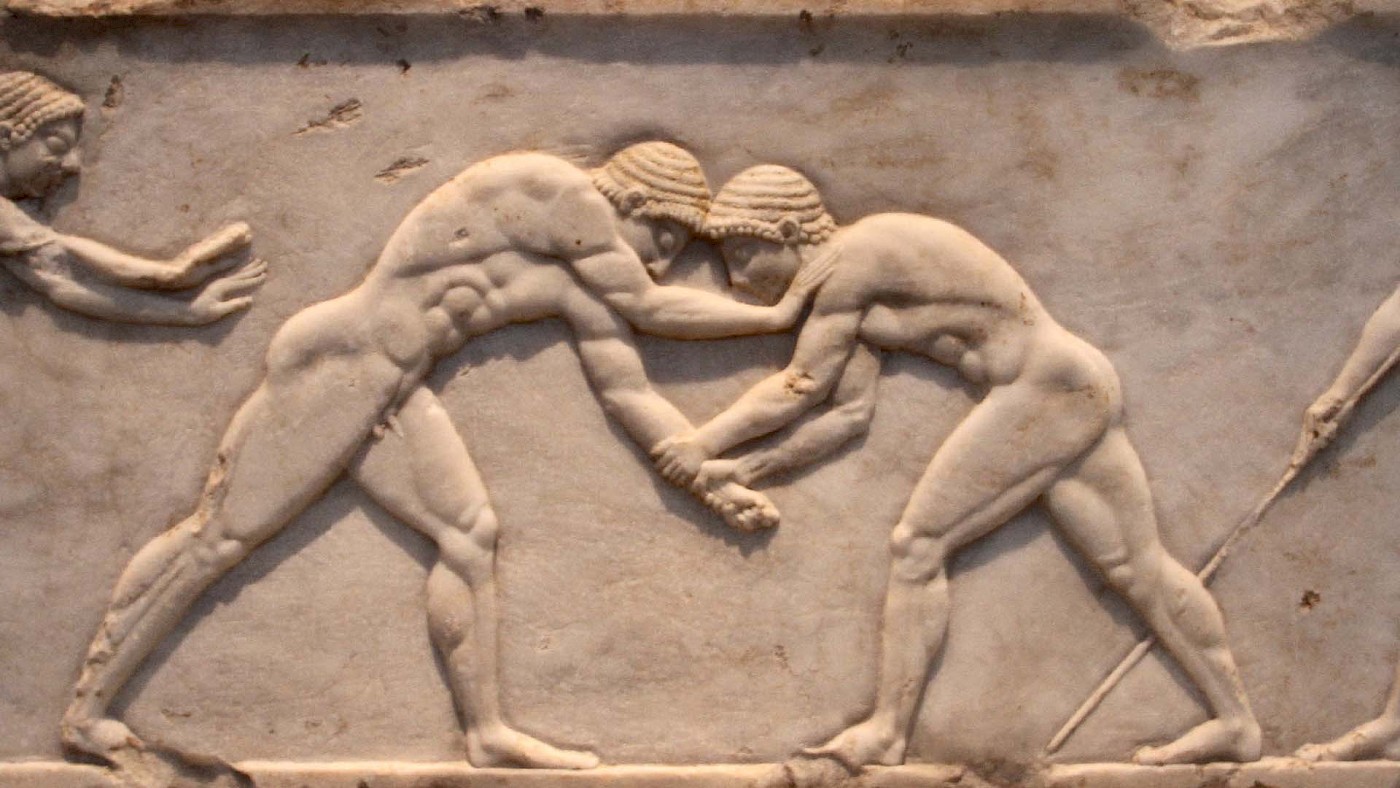

In the Iliad, the Greeks also organized wrestling and boxing matches. Both of these were staples of the ancient Greek sports repertoire. In boxing, pyx, both competitors wrapped their hands in leather straps and fought until one gave up or was knocked senseless. Wrestling, pale, focused on grappling; victory was given to the competitor who managed to throw his opponent to the ground. Not mentioned by Homer is pankration, sometimes referred to as an ancient Greek “martial art”: competitors were allowed to kick, punch, grapple, and throw their opponent until one surrendered or could not continue; only biting was not allowed.

Horses were important to the aristocracy and so it shouldn’t surprise us that chariot races were also a feature of Patroclus’ funeral games (Il. 23.262). We know that chariot racing dates back to at least the twelfth century BC, as Mycenaean vase-paintings from the Late Helladic IIIC period clearly show.

Single combat

During the games for Patroclus, Achilles issues a challenge for two men to fight each other in single combat. The winner would be awarded the spear, armour, and helmet of the Lycian hero Sarpedon, who had been slain by Patroclus. The winner would be the first man to draw blood from his opponent. Telamonian Ajax and Diomedes accept the challenge and after a short battle, Diomedes almost manages to cut Ajax’ throat, at which point the crowd cries out for the combatants to stop.

It is possible that ritualized single combat of the kind described in the Iliad was a common feature during the Archaic period, especially considering how popular the motif of duelling combatants is on Attic and Corinthian pottery of the seventh and sixth centuries BC.

Later games

The conventional founding date for the Olympic Games is 776 BC, but they presumably did not possess their Panhellenic character until the early sixth century BC, when similar games were also organized at Nemea, Isthmia, and Delphi. Some of the sports already mentioned, such as chariot races, were an important part of these games, and others were added to the repertoire, such as horse races.

Not found in the Homeric epics is the hoplitodromos, the race in armour or “hoplite race”. It was added to the Olympic Games at a relatively late stage, 520 BC, and added even later (498 BC) to the Pythian Games organized at Delphi. Whereas runners normally competed against each other in the nude, participants in the hoplite race wore at least a helmet and a shield.

Interestingly, the ancient Greeks did not engage in team sports. The one exception is a type of ball game that both adolescent boys and girls could engage in – albeit probably not in mixed teams – and where, after the match had been decided, the losing side had to carry the winners on their backs. There are statuettes depicting girls and boys playing the game that date from the fourth century BC and later.