The continent of Europe is named after a Phoenician woman called Europa. Her mother was Telephassa. Ancient sources differ on who her father was: according to Homer it was Phoenix (Iliad 14.321) – not to be confused with the hero of the same name! – but most other sources claim it was Agenor. (For further details, refer to Timothy Gantz, Early Greek Myth (1993), pp. 208-209.) Agenor, the son of the sea-god Poseidon and a mortal woman, ruled the Phoenician city of Tyre.

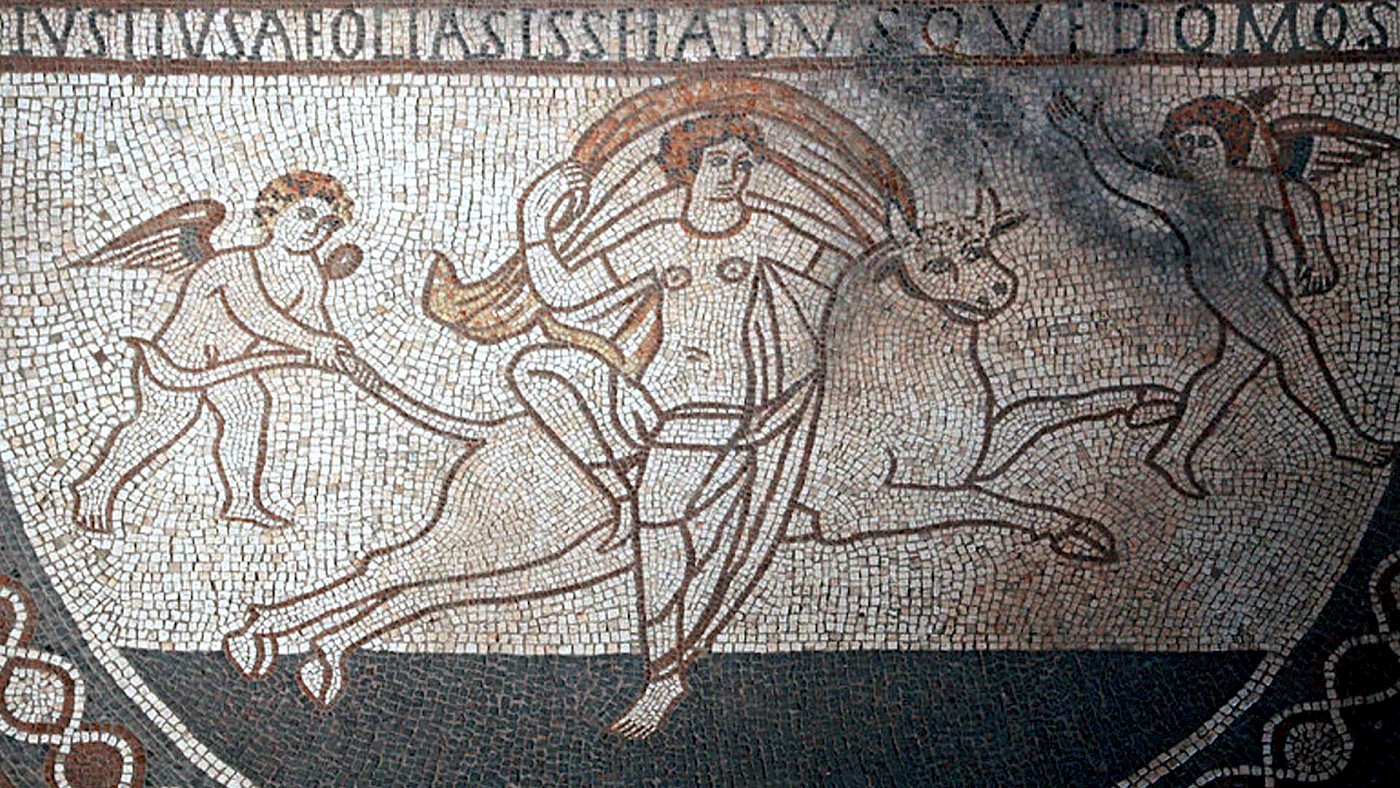

The rape of Europa

The story involving Europa is simple. She is often outside with other girls of her age, picking flowers or playing on the beach. One day, Zeus, the supreme god of the Greek pantheon, sees her and immediately lusts after her, as is his wont. And since Zeus is used to getting his way, he decides to simply take what he wants – albeit using a ruse.

Zeus transforms himself into a beautiful white bull. When he nears Europa and her friends, the girls are, of course, a little apprehensive. Where did this giant, gleaming white bull come from? Can it be trusted? But Zeus lays down at Europa’s feet and appears to be completely docile. Encouraged by her friends, Europa climbs on the animal’s back. Zeus gets up and slowly starts walking around. But soon, he accelerates his pace and eventually breaks into a gallop, with Europa clinging on for dear life.

Before long, Zeus and the frightened girl reach the seaside. Zeus plunged into the waves and quickly swam away from the shore, leaving Europa’s bewildered friends behind. It doesn’t take long for Zeus and his hapless victim to disappear from sight. Europa’s parents are beyond themselves, and Agenor sends out his sons to go look for her, telling them they ought not return without her.

However, none of Europa’s brothers would ever succeed in finding her, let alone bringing her back home. After all, mere mortals – even if their blood contains traces of the divine – are no match to Zeus himself, the “father of gods and men”. The brothers were eventually forced to abandon their search for their sister and founded cities of their own abroad. One of them, Cadmus, is credited as the founder of the Greek city of Thebes.

Europa in Crete

Zeus had taken Europa to the island of Crete, where he himself had been born and raised. Zeus had his way with her and Europa eventually gave birth to a number of sons. How many sons is a matter of some dispute in the ancient sources.

Some ancient writers – but most notably not Homer! – include the hero Sarpedon, who plays an important role in the Trojan War. Rhadamanthys, a more nebulous character, who is supposedly incapable of being deceived (as per Pindar’s Pythian 2), is often regarded a son of Zeus and Europa (e.g. Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.1.1). In the Odyssey, he is said to live in the “Isles of the Blessed” (4.564). In Classical times, he is referred to as a judge in the Underworld. Pausanias, in his description of Greece, makes a point of saying that Rhadamanthys was a son of the god Hephaestus, rather than Zeus (8.53.5).

The only figure from Greek mythology who is consistently described as a son of Zeus and Europa is Minos. He was appointed by Zeus as the ruler of Crete, with his throne at the city of Knossos. His wife, Pasiphaë, would later insult Poseidon, who cursed her and was ultimately responsible for her becoming the mother of the monstrous Minotaur.

Around 440 BC, Herodotus wrote a history of the conflicts between the Greeks and the Persians. At the start of the first book, he frames the Graeco-Persian Wars as the logical outcome of a long series of conflicts between the Greeks and Asians, in which the tit-for-tat raiding of women looms large (1.1-5). For our purposes, it’s interesting that Herodotus says that Europa, “according to Persian learned men”, was taken by some Greeks who had “landed at Tyre in Phoenicia and carried off the king’s daughter Europa” (Hdt. 1.2.1). Herodotus doesn’t mention Zeus here. Instead, he simply adds: “These Greeks must, I suppose, have been Cretans.”

Whether poor Europa had been abducted by a god or by mortal men, none of the ancient sources, as far as I am aware, make clear what happened to her in the end. As is so often the case with women in Greek mythology, she disappears from sight once she has fulfilled her purpose. But her memory has been kept alive. After all, an entire continent – Europe – has been named after the Phoenician princess.