Old World is a “4X” turn-based strategy game in the mould of Sid Meier’s Civilization. In a 4X game, you eXplore the map, eXpand your empire, eXploit natural resources, and eXterminate any opponents that get in your way. Old World boasts Soren Johnson as the lead designer; he was co-lead designer of Civilization III (my personal favourite in the series) and was lead designer on Civilization IV (widely regarded as the best instalment in the series).

Old World plays with the conventions of Civilization, but adds its own twists to the genre. Civilization is a game that spans the whole of human history, but Old World has a more narrow focus, limited as it is to the ancient world. But despite its more narrow focus, Old World doesn’t stray too far from the template first established by Sid Meier in the early 1990s.

The legacy of Civilization

Because the Civilization series has been around for three decades and its success is virtually unmatched in the turn-based strategy space, it has naturally attracted the attention of academics. Perhaps the best known critique is that of Kacper Pobłocki, who argued that Civilization is a product of American imperialism. In his article, “Becoming-state: the bio-cultural imperialism of Sid Meier’s Civilization” (2002), he writes (p. 168):

Civilization proves that the history of the West is the only logical development of the humankind that would have happened anywhere and any time, regardless of the initial conditions and players strategies. The garden designed by Meier merges all the possible paths into the master narrative of the Western success.

Certainly, Civilization is open to a lot of criticism. It is colonialist in that players – including AI-controlled opponents – start out with settlers in a completely unknown land that they have to explore and found settlements in. Along the way, they run into various kinds of natives, “minor tribes” who live in “tribal villages”. These usually confer some kind of bonus, like gold or a new “settlers” unit with which to found a new city, to the first player that moves a piece onto their tile, after which the village in question disappears. Players refer to these villages as “goody huts”: there is no attempt at a history lesson here (see also this Atlantic article by Luke Winkie on colonialism in board games).

Civilization V actually took a step in the right direction by replacing the tribal villages with ancient ruins, which conferred the same kinds of bonuses when they were first explored. Of course, regarding an ancient ruin as a source of some kind of benefit – maps, survivors, gold, artefacts, and so on – introduces a different kind of problem, but it’s probably a step in the right direction. Old World similarly uses ancient ruins rather than tribal villages. Coincidentally, Civilization VI took a step backwards when it removed the ruins of its predecessor in favour of reintroducing the tribal villages.

In addition, there are also barbarians, who serve no other purpose but to be hostile towards the player: one cannot reason with them, only eradicate them through violence. The ancient Greeks referred to people who spoke a different language as barbaroi (“bar-bar speakers”) and at least initially, this did not have any negative connotations. Herodotus, for example, wrote his Histories to commemorate the deeds of both the Hellenes and the “barbarians” (referring to the Persians). Civilization seems to stick to the outdated nineteenth-century idea of a “ladder of cultural evolution”, in which humans proceed from a stage of savagery to barbarism and ultimately civilization.

Civilization is imperialist not only in the sense that it reinforces a specific type of Western (American) imperialism, in Poblocki’s sense of the word, but also in that the game presents expansion as the only viable way to win the game. Not for nothing, Civilization’s tag line invites the player to “build an Empire to stand the test of time”. In addition, the original Civilization was inspired by the earlier game tellingly named Empire (1977), which itself took inspiration from, among other things, the board game Risk. One must found new cities to increase their overall economic output, and if no decent room is available to expand into, then other people’s cities must be taken by force.

Civilization also reinforces the idea of linear progress through the use of its technology tree: one advance leads to the other, and we ultimately progress from pottery and the wheel to rockets and computers. Indeed, Civilization emphasizes how things improve over time. In the official Civilization strategy guide (1992), Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich defined “civilization” within the context of the game as “a cooperative, interdependent population which is united in an improving lifestyle” (p. 344). They add (p. 345, original emphasis):

In short, to be civilized in terms of Sid Meier’s Civilization means to be making material progress in terms of economic well-being and scientific advancement. The game has an underlying belief in such progress. In fact, this dogma is so strong that there is actually no problem in Sid Meier’s Civilization that cannot be solved by human effort (using Settler units) or more technology.

The criticisms are well-founded and one might be disappointed, as I am to some extent, that even in the 2020s few 4X games seem to be willing to seriously challenge some of Civilization’s central tenets. In general, games embrace many of the problems that even trained archaeologists stumble over. Dealing not with games, but with archaeology in general, Rachel Crellin, in her book Change and Archeology (2020), refers to these impediments to our understanding of change as “hurdles”. They include many that ought to be familiar to gamers, such as the “block-time approach”, “progressive narratives”, and so on; see Matthew Lloyd’s review of her book for more information.

Multiple meanings

However, the criticism outlined in the previous section can, perhaps, only be taken so far when it comes to games. Diane Carr, in her 2006-chapter “The trouble with Civilization” (specifically, Civilization III), points out that criticizing Civilization for being colonialist and imperialist, and so on, is to focus very narrowly on “the game’s rules and its pseudo-historical guise” (p. 222). She points out that a game, especially one that is intended to be replayed and which has a global audience, cannot be reduced to “a single, definitive account of the meaning” (idem).

She takes inspiration from Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman’s Rules of Play (2004), which emphasizes that there are at least three different ways of looking at games: rules, play, and culture. Rules focus on the mechanics of the game: the functioning of its systems; these may indeed, as in the case of Civilization, have a distinctly pro-Western stance. Play emphasizes the experience different users have in engaging with the game. Culture seeks to place the game within a broader cultural context, for example by comparing it to other imperialist fantasies.

Games can be experienced differently by different players. Not everyone will take offence from the way that a game portrays certain aspects that others deem questionable. Experiences are, by their very nature, subjective. Carr offers an example about how different players interpret what Civilization III suggests about religion (p. 236, n. 4):

In a later conversation on Civ III, religion and anarchy it transpired that Player P thought that the game was suggesting that a religious population adjusted faster to changes in government because “faith grants the population strength or resilience”, whereas Player D (the author) had always thought the game was saying that a religious population is more biddable or docile.

Less successful in Carr’s essay is her statement that one cannot criticize Civilization for its historical trajectory being reductive: “That would be like disparaging a map for not being life-size” (p. 236, n. 6). While any game – or indeed anything that does not relate on a 1:1 basis with reality – is in essence reductive, one can still criticize the choices that the developers made in establishing the rules of their game, just like one can criticize a map, for example, for not including certain features or for being difficult to read. There are other trajectories that the developers could have taken instead of the one they picked.

Old World is certainly open to plenty of criticism, whatever a player’s experience of the game might be. For example, empire-building was of course a feature of the ancient world, but not all peoples – “nations” in the game’s anachronistic parlance – strove to expand their territories across the landscape. However, not doing so as a player leaves you at a disadvantage: hence, the game’s rules reinforce imperialism as a pathway to victory.

The game also doubles down on the notion of “barbarians”, which have to be destroyed to clear tiles so that players can settle there. This is a clearly colonialist way of looking at territorial expansion. There are also other, computer-controlled “tribes” that are merely there to provide some friction to the human players, with no intention of competing with the player in accomplishing any long-term goals of their own. In fact, a loading screen tip emphatically states: “Tribes are not nations.” And Old World’s technology tree – in any case a bit of an odd duck for a game set in the ancient world – is again entirely linear.

As the following will make clear, I take issue with certain of the basic assumptions underpinning the game’s rules. Many systems also strike me as needlessly complex. And, writing from the perspective of an archaeologist, I think it’s representation of the ancient world also leaves a lot to be desired. Nevertheless, with all of this out of the way, I would be remiss if I didn’t say that, as a game, Old World is certainly interesting. Interesting, of course, does not mean good – as I will explain in what follows.

The map, cities, and combat

In many ways, Old World follows in the footsteps of Civilization V, which was designed by Jon Schafer. Civilization V was the first game in the series to divide the map into hexagonal tiles rather than square ones. Inspired by games such as Panzer General, units trained in cities were also no longer allowed to be “stacked” onto a single tile; each hexagonal tile could only support a single unit.

In Civilization V, these changes led to all sorts of problems, most notably that the map quickly got congested. In an attempt to get rid of Civilization IV’s “stacks of dooms”, the fifth entry now suffered from “carpets of doom”, with a multitude of units shuffling back and forth in order to get in range of their targets. The AI wasn’t able to handle the changes well either, and even Civilization VI struggles to make the system work.

Old World also features hexagonal tiles and fully embraces the one-unit-per-tile (1UPT) rule. However, the scale is much smaller: rather than simulate an entire world, Old World simulates larger and smaller regions. As a result, the amount of actual ground represented by a single tile is much smaller than in Civilization, and there is, as a result, a lot more space to manoeuvre between cities.

The developers ensure that there is plenty of space between cities because you cannot found new settlement just anywhere. There are a limited number of “city sites” in the game. This ensures that, unlike Civilization, cities are spaced well apart, preventing any possible congestion of units on the map. I don’t think it’s feasible in most games to produce sufficient units to replicate Civilization V’s dreaded “carpet of doom”. A downside is that the AI seems to be pretty good at squatting on city sites, preventing you from settling there. This means that unless you’re very quick to expand, you’ll have to declare war against them sooner or later: this can be a bit frustrating.

Combat in Old World is further refined in contrast to Civilization V or VI by e.g. forcing you to unlimber catapults before you can attack with them, so you really need to think before you act. When cavalry units defeat an enemy unit, they gain the ability to rout: they can move into the tile occupied by the defeated unit and attack again, which means you need to use ranged units to weaken enemy troops sufficiently so you can break through their ranks. All in all, Old World manages to fully realize the original idea behind Civilization V’s one-unit-per-tile combat system.

One of the main innovations in Old World is the “Orders” system. In most strategy games, you can move as many units as you want. In Old World, your control of units is limited by the number of Orders you have available. This means that you can move several units during a turn or move one unit multiple times (up to its “fatigue” limit). During a war, you’ll probably try to move many units a short distance; once a war has started, the Orders system can be used to rush reinforcements to the front.

While, on the whole, I prefer more abstract combat in my turn-based strategy games, like the stacked combat in Civilization IV, I do appreciate the balancing act that Old World manages to pull off here, and the combat system itself gives dedicated turn-based tactical games, like the recent Fantasy General II, a good run for their money. That in itself could also be a criticism: Old World is even more of a wargame than Civilization V and VI. So if you don’t care about combat, you might have a hard time enjoying Old World.

Resources in Old World

Resources generally play an important part in strategy games and Old World is no different. Compared to other games in the genre, Old World has a fairly large amount of different resources. One of them are the “orders” that limit a large number of the actions you can take in a turn. Then there’s money, food, wood, stone, ore (iron), and various more abstract resources like civics and training. In addition to these 13 different resources (or “yields”), there are also other resources (goods) dotted around the map that give bonuses or can be traded as luxuries.

Among the more abstract resources are three that together do more or less what “production” does in a Civilization game. These are all resources that are representative of a city’s output capacity. In Civilization, the more production a city has available, the quicker it can build new structures or train new units. In Old World, there are three different types of production: growth (used for most civilian units), training (used for military units), and civics (used for specialists and for completing “projects” in a city).

I wonder if splitting production into three different types was a useful thing to do or if it adds more complexity to the game without good reason. Conceptually, I have a hard time wrapping my head around these resources, especially “training” and “civics”. They also play a role on a global level, where training can be used to allow units to march further than their fatigue level, and civics can be used to unlock new laws. Laws come in pairs and you have to pick between two options. They work kind of like the civics (!) system in Civilization IV, except they feel a bit more artificial here.

All of these resources can be stockpiled, but training, at least, has an upper limit of 2000 – any training above that gets converted into orders. But what on earth are “training” and “civics” in a concrete sense? How does a city “produce” training, let alone stockpile (!) it? How do “civics” allows me to unlock laws (once researched)? And what is “growth” exactly? In Civilization and other, similar games, like Humankind, population growth is a function of food surplus: simple and elegant. Here? I have no idea.

With Civilization, production is simply an indicator of a city’s potential to train units and build structures, since it depends on worked tiles (with or without improvements). I know that hill and mountain tiles added production, and imagined that this was because of the stones and metals that could be harvested there. In Old World, I have no idea what these abstract concepts are supposed to represent exactly.

Things are made more complicated by the fact that the game also has a variety of concrete resources that you gather from the map, not just food harvested from farms and the like. Old World also features “money”, which works the same as gold in Civilization. Scouts and workers can quickly cut down trees for wood or collect other resources out in the world. Wood, stone, and ore (iron) are the main resources that you gather in the game using lumber mills, quarries, and mines – all of which are constructed by workers on tiles you own.

Shuffling workers around the map to construct improvements is interesting at the beginning of the game, but quickly becomes a chore. The number of improvements you can develop also increases quite rapidly, meaning that you have to make a lot of decisions that essentially boil down to answering the question, “Which resource do I need now and/or in the immediate future?” What’s even stranger is that some improvements don’t even produce as much as you would expect until after you sacrifice a point of population to train a “specialist” to work that improvement, which strikes me as complexity for complexity’s sake.

Humankind, like Civilization Revolution, does away with workers altogether, and both of these games are much better for it. There are still ways to organize who does what within a city by selecting tiles to work (Civilization Revolution) or by dragging little icons to different workspots (Humankind). Real-time strategy games like Command & Conquer and Rise of Legends, as well as Mohawk Games’s earlier game, Offworld Trading Company, allowed you to build structures on the map without having to send out a worker to a specific spot first. Indeed, Offworld automatically sends out a little ship from your base to construct the building; something like that might have worked in a turn-based form, too.

The game does build on Offworld Trading Company by allowing you to simply buy and sell resources. But in the context of running a kingdom in the ancient world, this doesn’t make a lot of sense. Who do you buy these resources from? Who do you sell them to? In Offworld, you control a company on Mars and it makes sense for there to be some central market (Earth? the Martian colony?) where you can buy and sell resources. But here? It is a convenient game mechanic, but it make no sense given the theme of the game.

Like Civilization, “science” is a resource (“yield”) that you use to research new technologies (or “techs” for short). Dedicated research in a game set in the ancient world is a bit of an odd duck: there were no engineers slaving away in ancient universities trying to improve upon something in a dedicated research group or anything of that kind. As a result, it’s a bit of a missed opportunity to see essentially the system from the older games ported over to Old World.

There have been games that did more interesting things with research than Old World does. Here, there’s still an entirely linear research tree. The only wrinkle is that you now interface with it using a card system. Whenever you’ve researched something, the game draws a number of cards and you have to pick one of them. Most of these will be new technologies to research, while others are bonus cards that give you a free unit or resources.

This system doesn’t fundamentally alter the linear progression inherent in a “tech tree” and introduces a number of quirks. For example, the game’s soundtrack, which is really good, doesn’t play until you’ve research Drama. Likewise, automating scouts and workers require specific advances, too.

These choices seem like solutions in search of a problem. In the case of scout and worker automation, the thinking is probably that by the time those options are available, you will have so much stuff going on in the game that you would want to automate these relatively menial tasks. But again, was there no better way to solve this issue? I have always maintained that if there are parts of your game that are better off automated, you probably need to revisit your design.

To sum up, Old World features 13 different resources or “yields”, but they end up being mostly variations on the same thing. What, exactly, is gained by splitting Civilization’s production into three different types (growth, training, civics)? While introducing three different kinds of raw materials (wood, iron, and stone), the game also keeps Civilization’s gold/wealth resources (here: money). And each of these resources is gained in more or less the same way: by building improvements on tiles and/or adding specialists.

All these different resources do not, in my mind, create a richer experience. All these resources may add complexity to the game, but they do not add depth. This is, indeed, a fundamental problem in Old World in general.

Family business

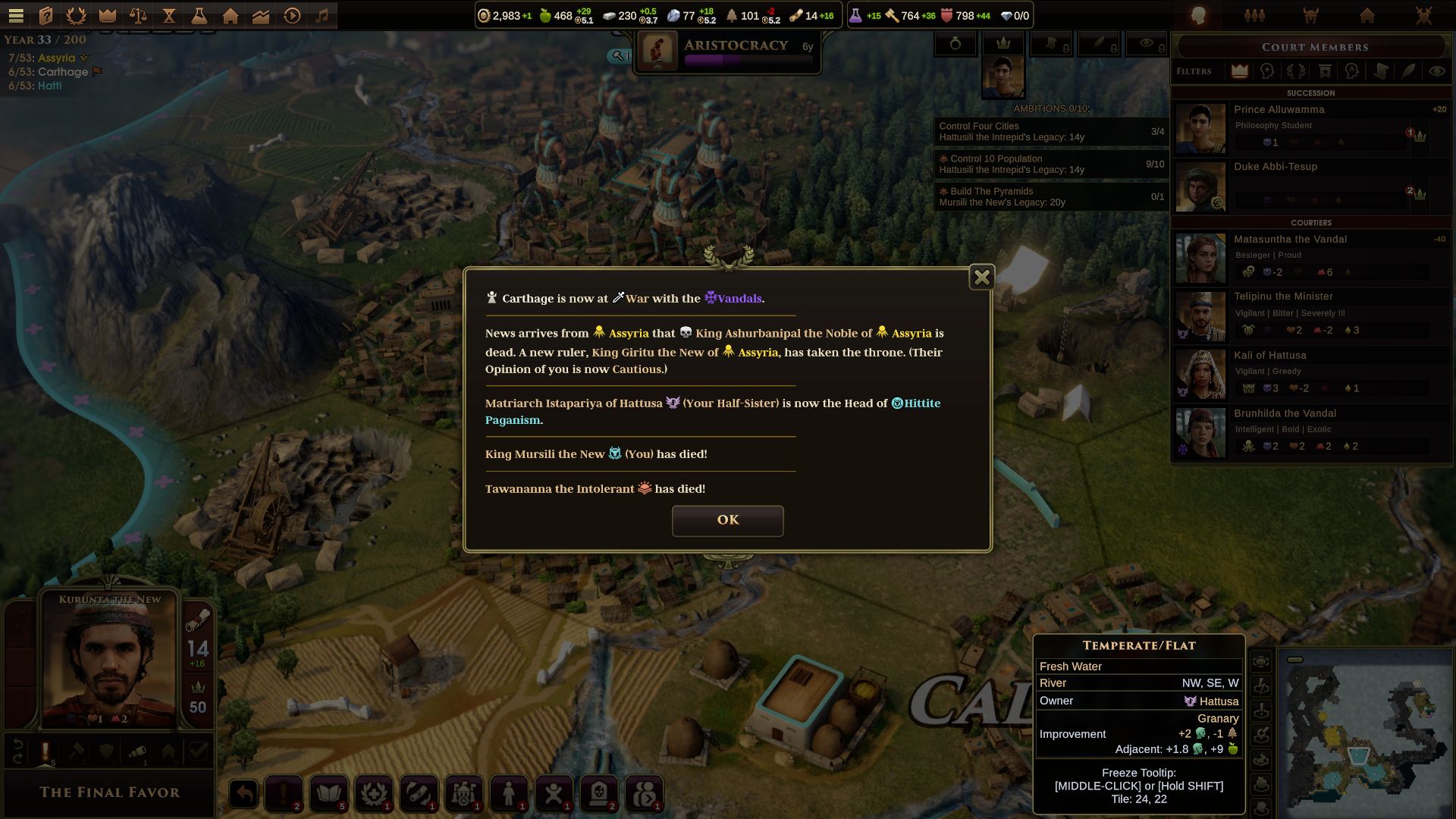

Old World also takes heavy inspiration from Paradox Entertainment’s Crusader Kings titles. In those games, the focus is on named characters. Old World incorporates families and named characters belonging to those families. It integrates them into an event system, with messages popping up frequently that so-and-so has fallen ill or changed their stats.

The focus on named characters suggests that the developers subscribe to the notion that history is the result of decisions made by a handful a people: history as driven by personalities, rather than history-as-a-process. As an archaeologist, I think the latter is a more accurate view of how the world has developed over time. But I do see the attraction in the former notion, especially when it comes to (role-playing) games and simulations.

The idea that powerful individuals make all the critical choices works for Crusader Kings because the characters are the game. Every game mechanic is tuned to play into this experience, to the point that it is more accurately described as a role-playing simulation, rather than a game with a definitive end state. The characters are also much more fleshed out than in Old World, allowing the simulation to generate genuinely interesting stories. Similarly, King of Dragon Pass and its follow-up, Six Ages: Ride Like the Wind, make characters and especially events a central part of the gameplay, to the point that the game’s map is not even their main focus.

In Old World, by contrast, the character system is much more bare-bones and feels like it was bolted on. As with the resources, it feels to me that the character system, and the associated events, are there to give the player more things to do, in the mistaken belief that more choices equal greater depth (and therefore fun?). You make decisions on the map as in a strategy game, and sometimes events will show up where you have to do something with a character.

For example, when you found a city, you need to assign it to one of the families in the game. This seems like it should be an exciting decision, but in practice, I haven’t been able to tell if the families really make much of a difference. You still have full control of that city. Nor does assigning governors to a city do anything aside from confer some bonusses that, honestly, I didn’t pay too much attention to because they didn’t seem to matter much.

In other words, Old World by default feels like I’m essentially playing two different games at once: the fun 4X-like game where I feel like I am making choices that seem meaningful, at least most of the time, and this weird, more or less random thing with characters where both the impact of my choices and my level of control (i.e. player agency) is limited. At times, the character system seems actively to work against what I am trying to accomplish on the map. It doesn’t feel meaningful in the sense that it doesn’t seem to lead to anything interesting.

Characters play a central role in diplomacy. In Old World, diplomacy isn’t a separate system where you barter with other leaders. Instead, you have to send characters out on missions, have your characters marry members of other “nations” and “tribes”, and so on. It all sounds good in theory, but in practice it comes down to clicking buttons and waiting for your choices to generate new events that you can respond to. It again feels a little ephemeral, devoid of much deeper meaning.

It doesn’t help that the results of these characters’ actions often get buried, especially later in the game, among the many, many other events that pop up that require you to make a decision, to say nothing of the notifications that appear. All of these choices and notifications, most of them lacking substance, means that it’s a much more tiring game to play than comparable strategy games. The developers tout that there are thousands of events, but I think more is less in this instance. In the end, all these events become noise that detract from the underlying game.

In short, then, the game’s characters introduce a number of different problems. They have traits that will limit your play in some way, and each character has an archetype (builder, hero, and so on). There are lots of characters, but none of them seem to have any personality. One picture attached to a collection of stats is more or less the same as any other picture attached to a different set of stats.

Another frustrating thing is that the characters introduce a random element to the game over which you have no control. They usually will fall ill and you cannot do anything about this: you just have to hope that they’ll get better again. And because there are so many characters, with none of them memorable, it’s a little hard to get too attached to any single one of them. They all blend together. So when person X dies, it’s usually met with a shrug.

The game insists on each turn being exactly one year, so it feels a little weird when you start a war with a rival and your leader ends up being 25 years older by the time you’re done. What is worse is that if your leader (i.e. your avatar) dies without having secured an heir, it’s game over. It’s weirdly incongruous, because am I really supposed to believe that if, for example, Philip dies without an heir, all of Greece simply packs up and leaves? Again, this might work if the game as a whole was centred on characters, but that’s simply not the case in Old World.

In one game, my leader was a healthy 30-year old. Then, one turn a little later, an event popped up saying that the seers had foreseen his death and he should prepare for his ultimate demise. A few turns after that, he was dead, and there was nothing I could have done to stop it. It was frustrating to see this happen, but since I wasn’t attached to whatever-his-name was (I honestly cannot remember), I continued the game with his heir. This death was, for all intents and purposes, a minor bump in the road.

I feel that each turn should last a much shorter amount of time, but I guess that might lead to other problems, not in the least because the game is limited, by default, to 200 turns. If each turn lasted only a month or so, that would amount to an entire game lasting a little shy of 17 years. That wouldn’t exactly allow for much to happen on the character front: who cares about heirs if the game is likely to be over before the leader gets ill and dies? And even if a turn lasted a season (3 months), the game would only last 50 years and the character system would again be kind of superfluous.

The impression that the character system is a more or less separate system from the rest of the game is reinforced by the fact that, during setup, you can simply switch the character systems off entirely and play the game like a regular turn-based strategy game! There is even a “chess mode”, which disables not just the characters and events, but even the fog-of-war.

As someone who doesn’t care about Old World’s character system, I greatly appreciate having the option to disable it. But I do wonder: if you can remove entire gameplay systems to get to the underlying core gameplay, should those systems be there in the first place? What of value, if anything, do they add to the core experience?

“Ludo-historical dissonance”

For a game supposedly inspired by history, Old World is characterized by what can most charitably be described as idiosyncratic choices with respect to how it presents the ancient world. Of course, whenever an expert points out historical inaccuracies in a work of fiction, it’s easy to see them as simply spoiling other people’s fun. “A game isn’t a historical documentary,” they might say. That is true and every player’s experience will be different. (Even though something like the recent Age of Empires IV proves that you can have a good game and offer something of educational value, too.)

However, if you have little interest in staying true to history, then why make a historical game in the first place? Games, just like movies, TV shows, and so on, might not be documentaries, but that doesn’t mean that creators have zero social responsibility when it comes to historical accuracy or – at the very least – ensuring that whatever they make at least feels authentic.

For example, with the “Definitive Edition” of Age of Empires III, the developers took the time to revisit some of the choices made initially with regards to their representation of Native American cultures. They wrote:

Speaking on civilizations, a key focus of our work at World’s Edge is to authentically represent the cultures and peoples that we depict in our games. While developing Age III: DE, we realized that we weren’t upholding that value as well as we could regarding our Native American cultures; so we set out to fix that: working directly with tribal consultants to respectfully and accurately capture the uniqueness of their peoples, history, and cultures. Returning players will find there’s been some fundamental changes to the Native American civilizations, and we hope you find them as compelling as we do!

This is not to say that Age of Empires III doesn’t have any problems. It does. Like other entries in the Age of Empires series, there are historical inaccuracies aplenty, but there is an attempt, at least, to be authentic, and to include historical information about the cultures depicted in the games, even if the information is often outdated – the original Age of Empires, especially.

The problem with Old World, is that it is full of historical inaccuracies and – even worse – doesn’t feel very authentic. The result is a kind of “ludo-historical dissonance”, where the game itself bears little similarity to its supposed inspiration. It starts with the available leaders for each of the available factions. Two of these are ficticious, namely Dido of Carthage, who is at best semi-legendary, and the entirely mythical Romulus of Rome. Right off the bat, these leaders strike me as weird choices for a game that purports to be historical. Why not pick, for example, Hanno the Great for Carthage, and any of a slew of well-known rulers and emperors for Rome?

The game itself clearly seeks to invoke the Classical world (ca. 500 BC to AD 500), with a strong emphasis on the Roman Empire. Much indeed seems to draw inspiration from later stages of the ancient era: for example, characters that are given aristocratic titles like “duke”, and artwork that shows a man with a crown sitting on a horse using a saddle with stirrups. However, the leaders in the game include two rulers of the Bronze Age, Hatshepsut and Hattusili, who feel entirely out of place. (Incidentally, the latter is identified as leading the Hatti, which is fine; his people are also referred to as “the Hittite”, which is wrong as it should be: Hittites. There are plenty such errors in the game’s many lines of text.)

Given the overall look and feel of the game, I think sticking to the Classical world, perhaps even the world of the first five or six centuries AD, would have been made more sense for this game. That would have allowed a sharper focus on the game’s theme and would have helped the whole feel more cohesive, at least as far as this archaeologist is concerned. While the differences should not be overstated, the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean was different in many respects to the world of the first millennium BC. Mixing different periods together leads to strange incongruities, like fielding large chariot armies as Philip or Alexander (fourth century BC) when there really shouldn’t be any, or starting out as Queen Hatshepsut (who lived in the 15th century BC) and gathering large amounts of iron!

Again, such aspects don’t really come across as strange when the scope of a game is wider, as in Civilization. But because Old World is much smaller scale, more comparable to e.g. Age of Empires, this kind of stuff sticks out. Similarly, cities and “urban tiles” generally seem to fit with the leader you picked at the start of the game: an Egyptian city, for example, looks suitably Egyptian. But it’s a little weird to then see a Worker unit construct a rather Roman-looking farm, complete with slanting roof and red rooftiles: visually, it doesn’t match at all with the Egyptian city. Similarly, you’ll build Roman-style theatres and even amphitheatres. No doubt this is a budget issue more than anything else, but it does take me out of the game.

That the Romans are the default faction is also reinforced in text. For example, the game insists on referring to an epithet – like “the Great” when applied to e.g. Alexander – as a cognomen, which is the Latin nickname by which Romans were most familiar. For example, in the name Gaius Julius Caesar, “Gaius” (Caius) is the praenomen or first name, “Julius” (Iulius) is the nomen or family name, and “Caesar” is the cognomen or nickname. Nicknames were often necessary because the pool of first names was limited, making it essential to have another way to distinguish between family members with the same names.

Similarly, when you win a game, you are greeted with the Latin phrase, “Ave imperator!” There are also various events that really only make sense when you’re playing as the Romans. Why, for example, when I play as the Hittites, do I get an event about something that is going on in the city’s “arena”, complete with a picture of a chariot in a Roman arena being chased by lions? It’s clear that the event refers to some kind of gladiatorial contest, but that makes zero sense in the context of playing as the Hittites! All of the foregoing, and much more, reinforces the idea that the default faction in Old World are the Romans, and especially the Romans of the Imperial era.

The Romans are, intentionally or not, the baseline with respect to this game’s representation of the ancient world. As a result, things feel a little off when you play as a different faction. I can understand that a small team might not have the resources to make every faction unique, but it wouldn’t take too much effort to at least modify the texts to make them a little more culture-agnostic, and to tag certain events to fire only with specific factions. Perhaps these issues will be resolved as development on the game continues? I have my doubts.

As far as look and feel are concerned, the game thus feels at its most authentic – though this isn’t really saying much – when playing as the Romans (despite featuring Romulus as its default leader!). It’s least authentic when you pick one of the Bronze Age leaders. The rest is sort of stuck in between, neither here nor there. I suppose if you don’t find this a problem – and, honestly, this could be the result of my own knowledge getting in the way of enjoying the game! – I imagine you might have a better time with Old World.

As you might expect, you shouldn’t play Old World if you’re expecting much in the way of historical accuracy. Given how badly it does, in my opinion, with representing the ancient world in general, it probably comes as a surprise when I say that the historical inaccuracies are numerous. Listing all of the game’s many inaccuracies would require another few thousand words in an already overlong review, so let me be brief.

At this point, I am no longer surprised about the fact that the material culture depicted in the game is all over the place. Many characters are shown wearing bracers, i.e. forearm guards of some sort, even outside of a military context. This reveals that Hollywood movies and TV shows like HBO’s Rome served as an inspiration for the visual side of the game rather than archaeological publications. What is even worse is that some structural elements are also entirely out of place, such as the use of aristocratic titles like “duke” and “duchess” in contexts in which they make no sense.

Soren Johnson introduced religion as a game concept to Civilization IV and a similar system is used here, but with some added weirdness. For example, it is now possible for members of prominent families to become the heads of certain religions. This is perhaps vaguely inspired by the Roman office of pontifex maximus, but its implementation here leads to oligarch so-and-so of this-or-that family to become the “head” of “Greek paganism”, as if everyone in the ancient world subscribed to some form of organized religion!

I have said this before and I will say so again: in this day and age, there is no excuse for these mistakes. There are literally hundreds if not thousands of ancient historians and archaeologists on Twitter, for example, many of who would be more than happy to give you advice or some recommended reading. If you have no interest in this and no desire to do any research of your own, that’s fine. But in that case, don’t make a historical game. Stick to fantasy or science-fiction instead, so you can make up whatever you want to create the best game possible.

Trouble with scenarios

4X games like Civilization often feature scenarios, which are custom maps with specific rules and victory conditions. Most players skip these scenarios, preferring instead to play a standard game on a randomly generated map. Old World has a fair number of scenarios that are grouped together according to a particular subject or theme. The game’s tutorial is, in fact, a series of five scenarios, each building on the other.

As a series of tutorials, these scenarios are pretty good. But the history showcased in them is decidedly ropey. You start out as Philip of “Greece” (should be Macedon, really). At some point, he is assassinated and it’s up to his son, Alexander, to solve the crime. Turns out Philip was killed by Thracians (!) at the instigation of the Romans (!), and now Alexander has to go and defeat the Roman army that is conveniently massing nearby.

This begs the question: who are these Philip and Alexander characters? Are they supposed to be Philip II and Alexander the Great? Philip was indeed assassinated in 336 BC, but not at the hand of Thracians: a young Macedonian named Pausanias struck the fatal blow. His reasons for doing so remain a mystery, but some claimed that he was operating at the orders of Olympias, Alexander’s mother and Philip’s wife, and others have suggested that Alexander himself was (also) involved.

Within the context of the game, I understand why the tutorial scenario is structured in the way it is, and it’s possible for Alexander’s life to take a completely different turn from what we know actually happened. But it showcases that the game isn’t historical in any concrete sense of the word. It is essentially a fantasy game playing dressup: it pretends to be a historical game, but doesn’t seem to be interested in the actual history it draws inspiration from. There is, simply put, no reason for this scripted (!) scenario to be ahistorical.

The problem with this tutorial scenario is that the designers deliberately do something that is contrary to established history without there being an explicit need to deviate from the facts. The end result is misinformation at best, disinformation at worst because of this conscious decision. The point of the scenario is to teach the player how to wage war against another player: Persia, not Rome, should have been the obvious opponent here. There was, as far as I can tell, no compelling creative reason to deviate from established fact: compare this choice – to pick just one random example – to the brutal killing of Adolf Hitler by American hands in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds (2009).

Misinformation, which is unintentional, and disinformation, which is intentional, are real problems with regards to representation of the ancient world. Creating a historical game should, as I have noted before, instill upon the designer a sense of social responsibility. Caring or not caring about this issue is in essence a political choice, especially in a world where the past is often abused with dire consequences for the present. As it is, I now eagerly anticipate people popping into Reddit’s AskHistorians to ask us if, for example, Philip II really was assassinated by Thracians!

To be sure, I have no trouble with a game presenting a historical scenario and then allowing the player to make different choices. Give us the Battle of Gaugemela and let us fight it as we see fit. This is something that the Total War games do well. Civilization, in a similar vein, puts all the pieces on the board and then allows players to create their own version of history in the guise of an immortal Alexander the Great, Abraham Lincoln, or Mahatma Gandhi.

I thought that perhaps the scenario pack that was released with the game’s launch on Steam and GOG.com would do something along these lines. The Heroes of the Aegean pack immediately made a terrible impression on me when I saw the art that was used to promote the pack: futuristic looking shields, often worn on the right arm (and in combination with a lower arm guard, too!), weird-looking spears, and helmets straight out of 300. We have a good idea of what warriors looked like in Greece in the fifth century BC: the sloppiness on display in the promotional artwork is execrable.

There are six scenarios in total. The first starts with the Battle of Marathon and the last focuses on Alexander’s successors. The opening text of the first scenario reads as follows:

In 492 BCE, the Persian Achaemenid Empire under Darius I invaded Greece. Persians seized much of Greece through combat and Greek capitulations but the Greek cities of Athens and Sparta refused to yield. After a break in the fighting, a large Persian force headed for Athens, intending to capture the city and then proceed to Sparta.

This short scenario serves as a prologue for the Heroes of the Aegean campaign, letting you recreate the Battle of Marathon, which marked a turning point in the conflict between Greece and Persia and is the reason why the word “marathon” is now so widely known.

This reads terribly: the game could have used a professional editor, and I am not just saying that because I happen to be one. There are also other problems with the text. For example, why is the word “marathon” so “widely known”? A marathon is a long-distance foot race created in the late nineteenth century to commemorate the distance that the messenger Philippides (or Pheidippides) supposedly traversed from Marathon to Athens to report the Athenian victory over the Persians. Is this what the writer of this blurb meant? Who knows.

Furthermore, the notion that the Persians “seized much of Greece” is misleading: the Persians were not interested in conquering the Greek cities. Unfortunately, the opening dialogue box when you start the scenario states explicitly that Persia sought the “subjugation” of “Greece”, and it paints Greece and Persia as “bitter rivals”. This is misleading at best, and it makes me wish that the developers had done their research better. Let’s provide some context here so you can better understand where my criticism comes from.

In the latter half of the sixth century BC, the Persian Empire conquered the Lydian Empire. The Persians eventually claimed the whole of Anatolia, which included the Greek cities on its coast. When these cities revolted in the first decade of the fifth century BC, some of the cities on the Greek mainland came to their aid. Once this “Ionian Revolt” (499-493 BC) had been quelled, the Persian Empire embarked on a punitive expedition to teach the Greek cities who had supported the revolt a lesson, especially Eretria and Athens.

In 492, the Persian army reached Macedon, but it was recalled because the Persian navy could not round the Athos peninsula. A second force was sent in 490 BC. This was a naval expedition against the Greek islands, Eretria and Athens. The Persians managed to lay waste to Eretria and they wanted to destroy (not capture!) Athens next. The army sailed south to Attica and landed at Marathon. The Athenians, assisted by a small allied force of Plataeans, managed to defeat the Persian army there. The Persians decided to fall back after this defeat. Contrary to what this blurb states, there is no mention in the ancient sources, as far as I know, that the Persians had intended to go after Sparta next.

It’s the Battle of Marathon that this first scenario focuses on and, as an aside, this reveals yet another weakness of the character system: democratic Athens, governed by its magistrates (archons), is granted a single leader in the form of polemarch Callimachus “the Intrepid”. Sigh. The game’s design is frequently at odds with the historical realities of the factions that they have included in the game, to the point where I don’t think there is any meaningful way in which the final product could be salvaged.

In any event, a decade after Marathon, Darius’ successor, Xerxes, mounted a third expedition to take revenge on the Greeks: in this encounter, they managed to destroy a small force led by the Spartans at Thermopylai and they also succeeded in burning down the city Athens: the insult of Marathon was repaid and Darius’ original objective in 490 BC – destroy Athens – accomplished. Afterwards, the Greeks managed to defeat the Persians first at a naval battle at Salamis (480 BC) and then on land at Plataea (479 BC). The Persians withdrew, but they would continue to meddle in Greek affairs until Alexander’s expedition against Darius III, ostensibly to take revenge on the Persians for having attacked the Greeks.

Of course, the Persian assaults loomed large in the minds of the Greeks and the history of these Greco-Persian Wars were immortalized in the Histories written by Herodotus, a native from Halicarnassus (in Anatolia), who had come to live in Athens. There is little to suggest that these expeditions were considered very important among the Persians. Leaving aside the factual inaccuracies for a moment, by embracing the Greek side of the narrative, Old World has lost the opportunity to do something more special with this particular scenario.

At the start of turn 2 of the scenario, the Persians land their forces at Marathon. You are told that the plain only has two “exits” and you can rush to block them. The option to acknowledge this goal reads, “Persia has numbers, but we have organization.” This feeds into a trope on ancient Greek warfare that the Greeks were somehow organized whereas the Persians were a disorganized mob. It is decidely orientalist, but not entirely without ancient antecedents: already in the Iliad, the Greek army advances quietly while the Trojans are a cacophonous rabble. Still, it would have been better for a game released in the 2020s to not lean into these stereotypes.

I cannot delve into great detail for each and every single one of these scenarios, but most of them have problems similar to what I have outlined above. As a whole, I think it might have been a more interesting choice not to release a DLC focused on Greece, but rather one that dealt with ancient Persia instead. We have seen various forms of media – films, books, comics, games – show the Greco-Persian Wars from a Greek perspective, thanks to the definitive history on the wars having been written by an ancient Greek. I don’t know of any game that focuses on the wars from the perspective of the Persian Empire instead. That might have actually been interesting.

The game by default also comes with a scenario pack that focuses on Carthage. Of course, there are issues here, too, with regards to historical accuracy, but at least these scenarios focus on an ancient city that does not get as much attention as, for example, its rival, Rome. The final scenario focuses on the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), which resulted in a Roman victory. The scenario specifically challenges the player to achieve a different outcome instead by having Carthage emerge victorious: this is more interesting than what they did with the Greek DLC.

Of course, Old World goes into far greater detail than Civilization or Humankind do. Those latter games are more abstract. Old World really relishes in the detail, but that does mean that if you’re even a little knowledgeable about the subject the game is trying to tackle, the many and often egregious mistakes in the game are probably only going to irrate you. They certainly get in the way of my own enjoyment of the game, to the point that I will probably never touch the game again now that this review is done.

Presentation issues

As far as art design is concerned, Old World looks a little drab, with lots of browns. It doesn’t look as vibrant as Civilization III or Civilization VI, let alone a more recent game like Humankind. In those games, the landscape appears to be bathed in perpetual sunlight: everything bright and, importantly, clearly legible. In Old World, the contrast on the map is sometimes a little low, and buildings and units blend together a bit.

The interface is wretched: a mess of small fonts and tiny icons. Most of the details are stuffed into tooltips: more small text, with no way to easily sift what’s important from what’s not so important. Why is the portrait of my leader so large in the bottom left corner if all of his stats are hidden inside a tooltip? Which resources should I care about? Is it money, since it’s the left-most resource? I don’t think so, but who can tell in this sea of icons and numbers?

When you start the game for the first time, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by all the information that is thrown at you in such a distinctly unappealing way. It’s simply not easy to look at the screen and gain a good idea of the current status of your game. Lots of dialogue boxes pop up throughout a session and all of them are boring boxes with one or more buttons to click. Other games, including earlier Civilization games, but also Humankind, did a much better job when it came to UI.

What frustrated me especially about the user interface is the game’s complete reliance on tooltips. Endless amounts of tooltips that you can freeze in place in order to hover your mouse over some tiny text that will pop up another tooltip. And you can then freeze that tooltip in place, too, so you can repeat the same thing, ad infinitum. At some points, most of my screen was filled with tooltips!

Surely, there must be a better way to convey necessary information to the user without needing them to exercise their mouse arm every few seconds to read yet another bloody tooltip. Why, for example, can I only get information about characters by mousing over them and reading an often very long tooltip? Why can I not simply pull up a character sheet that conveys the same information in a more user-friendly way?

I think an interface is best when it doesn’t draw too much information to itself. At various points in the game, I wished that the interface was more old-fashioned. I think I probably betray my age, but I wish designers would go back to using the left mouse to select and confirm actions, leaving the right mouse button to deselect, cancel, or call up more information about something. You know, how right-clicking a character portrait might pull up a character sheet?

What’s even worse is that the same information from the interminable tooltips is repeated verbatim in what passes as this game’s “encyclopedia”. I know I keep bringing up Sid Meier’s series of games, but Civilization’s “Civilopedia” is always an entertaining source of information, showcasing the best in outdated historical information. But at least it’s something. Some historical information about the game’s units, structures, factions, and concepts could have made for an interesting read, if only to get an impression of where the developers got their ideas from.

“Winning history”

A strategy game works best when it has a singular goal: when you, as the player, are working to achieve victory in a specific way. The original Civilization had two victory conditions: you won by either defeating all your rivals or by being the first to launch an expedition to Alpha Centauri. Later games in the series added more victory conditions, but they all boiled down to either wiping out your opponents or filling buckets with points.

Steffen Gerlach, the main designer of C-evo, a free turn-based strategy game based on Civilization II, wrote down a number of design principles for his Civilization-like strategy game, one of which is pertinent here:

Principle 3: AI Liberation. Empire building games are typically asymmetric. They are built around the human player as their center, with some pseudo-AI mainly having the job to keep him amused and to make the whole thing a realistic simulation. C-evo, in contrast, is a competition of equals. AI has no jobs, because that would reduce its strength. AI just has a goal, which is the same as the player’s goal: to win. All are playing by the same symmetric rules, no matter if human or AI.

Most strategy games similar to Civilization are to varying degrees a mix of an actual game and a simulation. The distinction between the two is important. In Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (third edition, 2016), Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al. write “that games are systems and have quantifiable outcomes” (p. 47); a simulation is also a system, but does not lead to a quantifiable outcome (e.g. a victory or a loss, or maximizing a player character’s level), indeed, a simulation in this sense does not need to lead to any outcome in particular (cf. also the discussion of genres on pp. 56-58).

Returning to C-evo for a moment, Gerlach suggests that newer Civilization games veer more towards simulation by creating AI that there are there to create friction for the player rather than the genuine opposition that another human player can offer. I think that is correct, especially with regards to Civilization V and Civilization VI, where more and more systems have been introduced that create friction for the human player; to give the human player more options to play the game to their own liking, often without much in the way of actual challenge. It also doesn’t help that the AI in these later games is essentially braindead: computer-controlled players are no match to human ones.

Old World leans heavily into the simulation side of things. One of the pathways to victory is open only to human players, namely by completing ten “ambitions”. These are objectives that pop up at regular intervals; often, you can pick between a number of options. For example, you might be tasked to assign governors to four cities or to build a specific monument. If your leader dies, ambitions that were assigned during his life become “legacy” ambitions and you have 20 years (i.e. 20 turns) to complete them.

That sounds like a good way to give players varied victory conditions, but I have yet to actually win a game via ambitions. Based on my own experiences with the game, ambitions simply don’t seem to be worth the effort. For example, an ambition that tasks you with assigning governors to four cities seems doable, but only if you already have four cities or if you can acquire them in some way – usually by force – relatively quickly. If you cannot, you migth as well not bother with this ambition and pick another one instead.

Here’s another example. I could pick from a small set of ambitions. I didn’t want to wage war against my neighbours, so I picked one that tasked me with getting four “courtiers” (and if this sounds medieval, it’s because it is). You can assign characters to your “court” only through events, and those events show up only once you’ve acquired a certain amount of culture. I put in a lot of extra effort to up the culture in my cities and managed to get two courtiers through events. Then my leader died and the ambition became a “legacy”, meaning I had only 20 turns to complete this ambition. I got one more before the 20 turns were up: in the end, I failed the ambition. It felt like a colossal waste of time.

The other, more sensible way to win – and the only way for the AI to win! – is through the acquisition of a set number of victory points (VPs). This works for a game rather than a simulation: it is literally a quantifiable outcome. The AI is quite adapt at racking up VPs as a game progresses; frequently, they outpaced me by quite a bit. The only way to stop the AI from winning, it seems, is to wage war against an opponent that has around the same amount of VPs that you do and then capture their cities. Since VPs are bound to cities (e.g. wonders and current development level), those points then transfer to you. This means that you must, sooner or later, wage a war of conquest, whether you want to or not – unless you’re content with just fooling around in the game and have no interest in winning.

The end result is that Old World, when played competitively, seems far more geared toward warfare than other, similar strategy games. That also means that its representation of the ancient world feels very reductive: a dog-eat-dog world in which the one with the largest army rules supreme. That strikes me as yet another missed opportunity, especially since the older Civilization games also tend to favour an aggressive approach.

Final thoughts

I have plenty of criticisms when it comes to Old World and how it treats its subject matter. With its more narrow focus, I wish the developers had taken its subject matter more seriously. Old World simply doesn’t give a fair representation of the ancient world. Worse, there is nothing in Old World that couldn’t be easily transferred to an alien planet or a fantasy realm of some kind, losing little if anything in the process.

Judged simply as a strategy game, Old World has plenty of problems. The character and event system feels like a separate game entirely from the Civilization-like game underneath. Like oil and water, the two never really mix. The former introduces a lot of friction in the game, much of which seems random and beyond the player’s control. Perhaps someone who simply wants to roleplay and roll with the punches will find it more to their liking.

The Civilization-like layer of the game offers a better experience, but one that seems strangely convulted compared to its obvious inspiration. The sheer number of resources (“yields”), the finnicky and overstuffed user interface, the orders system, the card system used for research, and lots of other different mechanics that seem to be there just to be different, without any clear benefit to the experience of the player. Old World is more complex than most Civilization games, but it doesn’t mean it has more depth. More is definitely less here. It’s too complex for its own good.

Perhaps the best element of the game is the combat system, which rivals the quality of dedicated turn-based tactics games. Unlike the more cramped combat in Civilization V and Civilization VI, the maps generated in Old World give you plenty of room to manoeuvre. Old World is at its best, in my opinion, when you disable the character system and play it like an empire-building game with some peudo-historical flavour. But then it does reduce the game to what is essentially a wargame, which is also not helped by the fact that waging war is the easiest way to win a match.

Much to my own surprise, I found myself frequently bored with the game. It’s not that there isn’t anything to do – if anything, the game has too much to do. But so much seems like utter busywork – as if Old World is afraid that your thoughts might stray – that decision fatigue sets in sooner rather than later and my eyes simply glaze over. And while switching off the character system creates a better experience compared to the standard game, it doesn’t strike me as an improvement over virtually any other 4X game I could be playing instead.

Such games include the venerable Civilization III, which struck me, after spending many hours with Old World, as an oasis of elegance. The user interface is minimalistic; its systems are easy to comprehend, yet allow for great depth. Or what about Alpha Centauri, a game brimming with character but without the randomized Crusader Kings-adjacent nonsense that feels so out of place in Old World. And Old World has also made me appreciate Humankind more. That game certainly has its problems, as I’ve explained before, but it’s an infinitely more elegant game, with a much more modern and user-friendly interface. All these games offer, at least to me, a better experience than Old World.

In short, then, I do not recommend Old World. Of course, you might enjoy the game more than me, especially if you don’t mind its (mostly) randomly generated characters and events, the plethora of historical inaccuracies and its overall lack of historical authenticity, and if you can stomach the fussy user interface.

Old World is available on all the main platforms: Steam (Windows, Linux, Mac), the Epic Games Store (Windows and Mac), and GOG (only Windows).

Further reading

- Diane Carr, “The trouble with Civilization”, in: Barry Atkins and Tanya Krzywinska (eds), Videogame, Player, Text (2006), pp. 222-236.

- Rachel Crellin, Change and Archaeology (2020).

- Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Jonas Heide Smith, and Susana Pajares Tosca, Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (third edition, 2016).

- Kacper Pobłocki, “Becoming-state: the bio-cultural imperialism of Sid Meier’s Civilization”, Focaal: European Journal of Anthropology 39 (2002), pp. 163-177.

- Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals (2004).

- Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, Sid Meier’s Civilization, or Rome on 64K a Day (1992).

- Luke Winkie, “The board games that ask you to reenact colonialism”, The Atlantic (2021; accessed 20 June 2022).