The original Prince of Persia was published in 1989 and created by Jordan Mechner. The game is a 2D platformer, notable for its use of rotoscoping to create fluid and realistic-looking animations. While initially without a particular theme, Mechner was eventually encouraged to pick an Arabian Nights-like setting and plot for the game.

The story of this very first entry in the series is simple. With the sultan off to fight a war, his evil Vizier seizes the throne. The sultan’s daughter is locked up and to be executed in one hour precisely. The Prince, who serves as the game’s player character, is in love with the princess and has been thrown into the dungeons of the palace. It’s your task to escape and run, jump, climb, and fight your way to the Vizier.

The original game was incredibly successful and ported to virtually every computer system and console imaginable. It spawned the genre of “cinematic” platforming games. A sequel was released in 1993, subtitled The Shadow and the Flame, also developed by Mechner.

A different development team worked on the third instalment, Prince of Persia 3D, which was a three-dimensional polygonal game influenced by Tomb Raider (1996), which itself featured the kind of realistic platforming that the original Prince of Persia had introduced in the late 1980s.

Enter Ubisoft

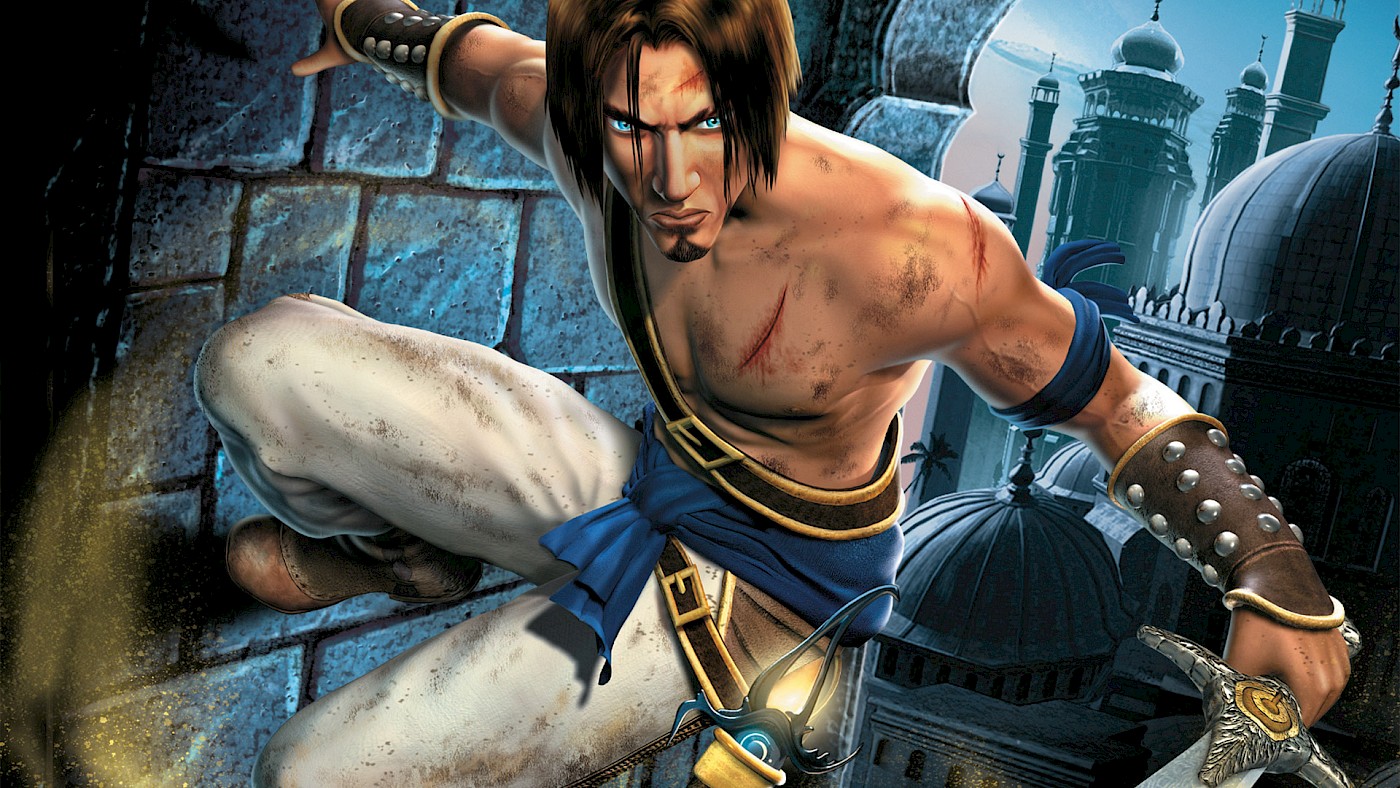

Prince of Persia 3D was not a success due to its stiff controls and unappealing graphics. But in the early twenty-first century, Ubisoft acquired the rights and began work on a new 3D game in the series. Mechner was shown some early gameplay and was so enthused that he joined the development staff and wrote the game’s story. In 2003, the game was released. Prince of Persia: Sands of Time was a critical and commercial hit and spawned a new series of games.

Each of the games is set in a single location. In The Sands of Time, you’ll explore an Indian palace. In Warrior Within, you’ll explore the “Island of Time”, while in The Two Thrones, you’ll run, jump, and climb around the city of Babylon. In 2008’s Prince of Persia, the setting is a sprawling, but otherwise unnamed Persian city. In The Forgotten Sands, you’ll explore another unnamed city that is associated with King Solomon.

The gameplay in all of the Prince of Persia games rests on three main pillars: traversal in the form of parkour-like platforming, combat, and solving fairly simple puzzles. Presentation tends to be top-notch, with the first game essentially launching the genre of the cinematic platformer. Despite their age, the games all still look fantastic, with great level design and smooth animations.

Since there’s actually quite a lot to write about, this article is divided into two parts. The present article deals with the original Sands of Time trilogy, released between 2003 and 2005. The second part of this article will focus on the most recent mainline games: 2008’s reboot Prince of Persia and the 2010 instalment The Forgotten Sands, which is a direct sequel to The Sands of Time and a prequel to Warrior Within. I’ll also briefly touch upon the notion that the series is an Orientalist fantasy.

The movie adaptation from 2010, released by Disney, won’t be discussed here. The 2008 graphic novel, entitled simply Prince of Persia, is worth checking out for both its artwork and its strangely complex plot; I’ll also reference some of creator Jordan Mechner’s notes in that book in the following discussion.

The Sands of Time

In Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, the Prince is a brash young man who joins his father, King Sharaman, in the siege of an Indian city. He finds his way inside and steals a dagger. A little later, it’s revealed that the Maharaja’s Vizier had traitorously instigated the attack in order to gain possession of a magical hourglass. When he sees the Prince with the dagger, he demands to be given it. Sharaman refuses, saying that the Prince should hold onto it as a keepsake.

The Vizier then manages to trick the Prince into using the dagger as a key to open the Hourglass. When he does, it releases the eponymous “Sands of Time”, which the Vizier believed to grant immortality. Everyone in the palace is turned into a sand monster with the exception of the Vizier, the Prince, and the Maharaja’s daughter, a princess called Farah. The reason that they didn’t turn was due to magical items: the Vizier had his staff, the Prince had the dagger, and Farah was protected by an amulet.

With the Sands released, it’s up to the Prince to correct his mistake. As in the original game, he has to run, jump, and climb his way through the palace to reach the Vizier. Aside from difficult jumps, where it’s sometimes easy to fall to one’s death, the palace’s defence system has also been activated, meaning that there are various traps that the Prince has to overcome.

Fortunately, the dagger turns out to be the “Dagger of Time”, a magical weapon that allows him to rewind time, an ability limited by the number of full sand tanks he has at his disposal. This means that accidentally jumping into a pit with spikes is no longer an automatic game over: you can rewind time and correct the mistake. This feature made it in all of the subsequent Prince of Persia games with the exception of the 2008 reboot, but that entry had its own take on avoiding death that I’ll get to later.

The game is noteworthy not just for its gameplay, excellent graphics, and atmosphere, but also for its story. The Prince starts out as rather arrogant and naïve. Over the course of the game, however, he undergoes some actual character development. His changes come about mostly though his interactions with Farah, the Maharaja’s daughter.

Initially, the Prince comes across as a misogynistic asshole, even at one point suggesting he might marry Farah and “tame” her. But as time goes on he comes to appreciate the strong-willed princess and realizes the folly of his ways. At the end of the game, he’s become a wiser, more understanding person as a result.

In the notes to the Prince of Persia graphic novel, published in 2008, Mechner says that the earlier Prince of Persia games were only vaguely set in a world inspired by the stories of the Arabian Nights. For Sands of Time, he says that he wrote a guide to the world of the Prince and hammered out a lot of details. By this time, he had read the Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”), Iran’s national epic composed by the poet Ferdowsi.

Even though the Shahnameh dates to ca. AD 1000, the poem contains a lot of older material. Its contents covers a period of time from the creation of the world until the Islamic conquest of Persia in the seventh century. In The Sands of Time, the Prince references the legendary hero Rustam as a shoutout to the Shanemeh. Rustam or Rostam is one of Iran’s greatest heroes; the trappings of his story suggests that his tale perhaps dates from the Parthian period of Persian history, so between 247 BC and AD 224.

Mechner set the game specifically in the ninth century AD, which he regarded as “a time of warfare and intrigue”. The Sands of Time is thus set after the islamization of Iran. The game takes place entirely within the Maharaja’s palace, which looks suitably Indian and features Oriental trappings that border on cliché but nevertheless work within the context of the game.

The Sands of Time set the standard for all of the Prince of Persia games to follow. While the platforming is generally fairly simple, it does require you to become familiar with the Prince’s moveset in order to figure out the best way out of some of the more tricky rooms. In some instances, the game tests you by including a timer in the form of a slowly closing door, forcing you to move through the environment as quickly and as efficiently as possible.

The game isn’t just about platforming: it contains a fair share of combat, too. Back when the game was released, the combat system was heavily criticized and for good reason. Combat is fairly dull: you’ll fight against a variety of sand creatures, which, nine times out of ten, you have to weaken and then stab with the Dagger of Time to dispatch them completely. There’s not much variety here: you’ll either leap over enemies and perform a downward slash or launch yourself from a wall at them to dispatch them the quickest way possible, which isn’t very quick at all.

Still, The Sands of Time is fondly remembered for a reason. The controls are tight, the platforming is inventive, the puzzle rooms are memorable, and the atmosphere, story, and characterization is top-notch. The game’s widely heralded as a classic, and it’s not hard to see why.

Chased by the Dahaka

The Sands of Time was a self-contained story with a solid ending. But since the game was a commercial success, Ubisoft immediately began creating a sequel. The result of their efforts was the release, only a year later, of The Warrior Within (2004).

Seven years have passed since the first game and the Prince is being chased by the Dahaka, an entity tasked with restoring the timeline. While the Prince succeeded at the end of The Sands of Time to restore everything to how it was, he himself was fated to die and the Dahaka is tasked with killing him. This sets up the theme for the game and its sequel, namely whether or not one can change fate. After being on the run for a while, the Prince learns that the Sands of Time were created on the Island of Time, and he sets off for the island with the intention to prevent the Sands of Time from ever being created in the first place.

This game drastically altered the character of the series. Whereas The Sands of Time was a pleasant affair with a soft-spoken Prince, this new entry sports a more overtly heavy metal soundtrack (including a song by Godsmack!), features more gruesome death animations for enemies (such as them sometimes being cut through the middle), sexualizes the female characters, and so on. The loading screen even features a stylized hourglass filling with blood. Subtelty is not Warrior Within’s strong suit.

Furthermore, the Prince’s original voice actor (Yuri Lowenthal) was swapped out for this entry and replaced by a more gruff-sounding guy with a more pronounced American accent. The Prince himself also sports longer, more unkempt hair. The tone is set in the opening sequence of the game, where you fight a woman clad in an iron thong and where the Prince calls her a “bitch” after she cuts him across the face with one of her blades.

Nevertheless, if you can get over the rather drastic shift in tone, there’s a good game here. The traversal is as good as in The Sands of Time, with the Prince now also being able to slide down banners along the wall to safely reach the ground. The puzzle rooms are just as interesting and as challenging as in the previous game.

Combat was the weakest part of The Sands of Time and it has been completely revamped for this instalment, with the Prince being able to pick up weapons dropped by enemies, perform various combos, swing round columns while slicing with his sword, and perform a variety of different, often quite impressive looking moves. As a result, the game features quite a bit more fighting in this game than in the previous instalment.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if savepoints were more frequent. In Warrior Within, you can save the game only when you drink from a fountain. Unfortunately, the game has the tendency to put combat sections at the end of often quite intricate platforming sections, and losing the battle means that you have to do everything over again. This can get a tad frustrating, but when things don’t go your way it’s often best to take a break and try again later.

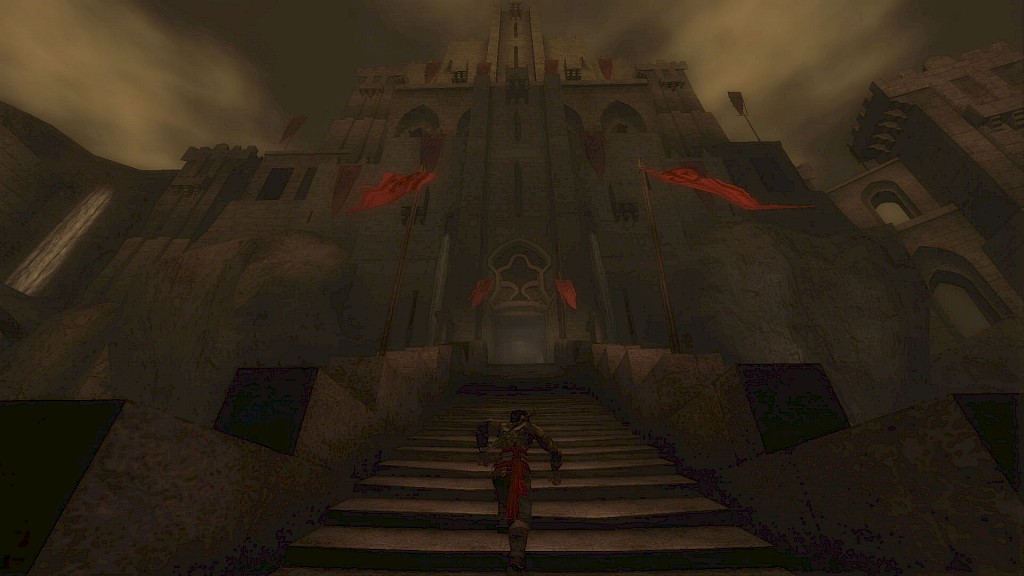

The game’s setting, the “Island of Time”, is entirely an invention on the part of the developers. The architecture here is a middleground between the more Oriental stuff seen in The Sands of Time and more generic medieval fantasy type of stuff. An interesting feature is the inclusion of portals that allow the Prince to travel between two different time periods: the present, when the island is rundown and all but abandoned, and the past, when the island looks pristine and all the traps inside the structures are fully functional.

There’s not much in this game that was based on anything historical. In the opening cinematic, we get a brief glimpse of Babylon, the setting of the next game, including the Tower of Babel, which appears to be modelled after the Minaret at the Great Mosque of Samarra. The ships that we see at the beginning of the game don’t really correspond to any particular time period. Among the mini-bosses, you’ll find golems, which are creatures from Jewish folklore that are made entirely of inanimate matter, such as stone or clay.

The monster chasing the Prince, the Dahaka, derives his name from Azhi Dahaka, also known as Zahhak, an evil figure from ancient Persian mythology and folklore, who also plays a role in texts atributed to Zoroaster (also known as Zarathustra).

In Iranian mythology, the Dahaka is part serpent; in the game, it’s depicted as a monster seemingly made of thick, black smoke from which tentacles emerge when it’s about to latch onto the Prince. The creature is ultimately defeated by the Prince using the Water Sword. This is undoubtedly not a coincidence: according to Zoroastrian belief, water is one of the “pure” elements (alongside fire).

A tale of two princes

The Warrior Within was a hit, but also proved divisive. Many people who had played The Sands of Time were understandbly upset about the angrier, more violent tone of the sequel. Newcomers to the series that enjoyed the harsher nature of Warrior Within didn’t care for the lighter tone of the prequel. So when Ubisoft started development of the next game they were faced by a bit of a quandary.

The result is The Two Thrones, which embraced the dual nature of the Prince by essentially creating a mix of the first two games. It picks up where the “good ending” of The Warrior Within left off. The Prince and Kaileena, the “Empress of Time”, are on a boat and within reach of the city of Babylon when they are attacked by an unknown army. Kaileena gets taken and the Prince has to find his way through the beleagured city.

He soon discovers that by undoing the events of the previous games, the Vizier from The Sands of Time is still alive and looking for the mythical Sands. He captures and kills Kaileena, thereby somehow releasing the Sands of Time again. The Prince gets struck by the blast while having a metal whip (a “Daggertail”) wrapped around his arm, and he’s changed as a result: now part sandwraith, at some points during the game he is transformed into the Dark Prince, while an evil voice occassionally prattles inside his head.

In essence, the story is a bit of a retread from The Sands of Time. It was also a curious design decision to have the Dark Prince manifest himself only in certain parts of the game, which always end with the Prince stepping into water and transforming back. The Dark Prince sequences also tend to focus more heavily on combat, but those fights are usually incredibly easy, since your main weapon is the Daggertail, which you can simply swing round and defeat most enemies with in short order.

Combat hasn’t changed much compared to The Warrior Within. The main difference is that the primary weapon is again the Dagger of Time (as in the first instalment), which is fairly weak. Since secondary weapons still break far too easily after being used a few times, you’re constantly on the lookout for fresh weapons to make the combat drag on for too long. As an aside, who thinks that limited weapon durability is actually fun? Anyway, savepoints are sometimes still spaced a bit too far apart, forcing you to redo large parts of an area if you’re killed.

Sadly, combat often drags on for too long in this game, especially if you play at the normal difficulty or above. If you’re without a secondary weapon, you seem to do next to no damage. In the heat of battle, it’s often very tricky to stop and pick up a weapon without getting hit in the meantime. There are also enemies who’ll drain your sand, meaning that they essentially rob you of your ability to rewind time, thus making fights even more frustrating when you have to replay them multiple times after getting a game over screen.

However, the Prince now has a new “Speed Kill” ability that allows you to forego combat entirely. If you approach an enemy unseen, the screen will get a yellowish tint, indicating that you can perform a “Speed Kill” (i.e. a stealth kill) by tapping the secondary attack button. The blade will flash once, twice, or three times, at which point you have to tap the attack button. If you press the buttons in time, you’ll dispatch the enemy easily. Miss a beat and you’ll have to fight them the old fashioned way (or rewind and try again). Sometimes, button presses don’t seem to register properly, but these occurrances are few and far between.

The traversal moves have been expanded with an ability to use wooden plates to jump quickly from one wall to the next, and the Prince is also able to keep himself suspended between narrow spaces, such as between two buildings, and slide down or climb up them.

The game also features Farah again, the Prince’s companion from the first game. Naturally, Farah doesn’t remember the Prince at all, since the events of the first two games were undone by the Prince’s actions on the Island of Time. Their interaction in this game is fine, but it lacks the magic of The Sands of Time. The ending, however, does bring things nicely full circle and works in bringing the series to a close.

As far as the historical aspects of the game are concerned, we seem to have somehow travelled backwards in time. Babylon features a tall tower, presumably in a nod to the biblical Tower of Babel, which lends the game an ancient flair. The game also features the “Hanging Gardens”, mentioned by Herodotus in the fifth century BC, but which were probably not located in Babylon.

Furthermore, the Vizier has somehow allied himself with the Scythians, which is rather peculiar: as a people, they flourished from before the sixth century BC to around the fourth century AD, when they largely faded from history. Of course, the Scythians’ armour and weapons are clearly not based on archaeological evidence, but instead appear to be wholly fantastical. That much is par for the course.

Babylon itself features largely timeless architecture of the sort that you might still find in the Middle East. Wooden extensions built to rooms suggest to me some medieval influence, but on the whole it’s difficult to date the game based on the architecture of the buildings it features. Curiously, the Scythians at one point round up citizens to take them to the arena, where you’ll also engage in a boss fight. Naturally, arenas were used only by the Romans; the Persians or Babylonians didn’t see combat as a form of entertainment.

All in all, though, this is still a good entry in the series. The game’s tone isn’t as light as The Sands of Time nor as dour as The Warrior Within, but for the most part it works. Combat can be frustrating, so I’d recommend you’d play this on easy, especially since once you pick a difficulty setting there’s no way to adjust it once you start playing.

Continued in part two.