Nestled in the mountains in the eastern part of Crete, 3 km from the village of Kritsa and about 10 km from the coastal town of Agios Nikolaos, are the remains of the ancient city of Lato. The city is presumably named after the goddess Leto, the mother of Apollo and Artemis. (In Dorian Greek, the ancient Greek dialect spoken in Crete in the historic era, Leto is written as Lato.)

The remains of the ancient city are exceptionally well preserved. Most of the structures currently visible date to the fourth and third centuries BC, so the Late Classical and Early Hellenistic periods. However, terracotta figurines and plaques unearthed at the site have revealed that the earliest phase of the city probably dates back to the seventh century BC. Late Minoan IIIC pottery fragments suggest that the site of the later Archaic and Classical city may also have been inhabited in the twelfth century BC.

A defensible location

The town was built in a highly defensible position, on a double acropolis, around 300 to 400 metres above sea level. Lato was protected by a strong circuit wall. To access the ancient city, you need to take a path from the entrance of the site that takes you to the main gate. This is the same route that visitors to the city would have taken in the Late Classical and Early Hellenistic periods.

The slopes of the mountain were terraced to make it easier to construct all the necessary buildings. Most of the structures currently visible are houses. The main street consists of steps that lead from the gate to a relatively large, flat area in between the site’s two peaks. This was Lato’s agora, the central meeting place of any ancient Greek city of the historic era.

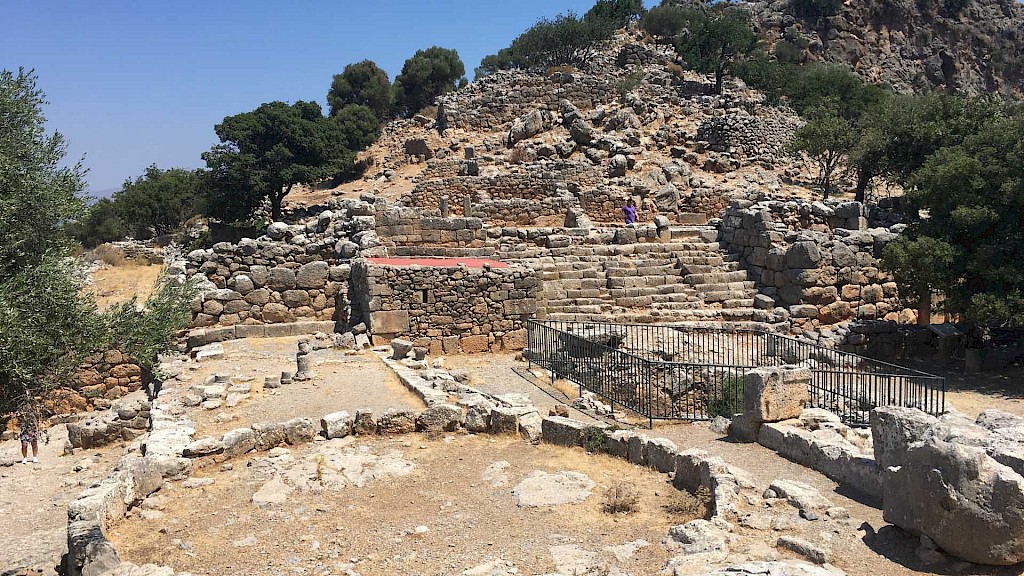

Located so high up in the mountains, water was no doubt a problem for the ancient Latians. In the centre of the agora is a large and deep cistern, with steps leading from the surface down to the bottom to make it easier to access the water. The importance of this cistern is emphasized by the fact that the structure directly to the south of it was a temple, although we don’t know to which deity is was dedicated; perhaps it was Leto. Most houses also seem to have had private cisterns that were markedly smaller, and which were probably fed by rainwater.

Along the northern edge of the agora is a broad flight of steps that were used as seating for people to listen to whatever was going on in the agora. There are enough seats to accomodate around 80 people. Beyond the steps lies the prytaneion complex, which dates to the second half of the fourth century BC. This is where the prytaneis gathered, the people who were effectively in charge of the town’s government.

Located not far from the main area of the agora, to the southwest, is a relatively narrow ridge where we encounter more seating. This is part of the so-called “Theatral Area”. The seats here would have afforded space for around 350 people. Whether or not this was an actual theatre is disputed: it may have been an ekklesiasterion, an assembly place for the ekklesia or popular assembly. Of course, one function doesn’t necessarily exclude another.

At a higher level from the Theatral Area are the remains of another temple, built out of large, worked blocks of stone. We again don’t know which deity was worshipped here. The Latians may also have controlled a large extra-urban sanctuary located 1.5 km south-east from the city on Mt. Thilakas. By organizing processions from the centre of town to this sanctuary, the Latians were able to demonstrate the control they exerted on the surrounding territory, where they must have had farmland and pasture.

It is clear based on the archaeological evidence that the Latians slowly abandoned their mountain city and moved to Kamara, the remains of which are currently beneath the modern town of Agios Nikolaos. Kamara was easier to reach than Lato; closer access to the coast would have helped with trade. The archaeological site can today be reached by car or you can rent a taxi from a nearby settlement.

Gallery

The gate

Nestled in the mountains, Lato’s position was highly defensible. Still, the ancient Latians further protected their city with a circuit wall. Access to the settlement is afforded by this gate, which is the only way for visitors today to enter the site.

Immediately beyond the gate

This is the area immediately behind the gate. There’s a street here and various structures. Because the buildings were all made of stone, a lot of the structures have been preserved, so that you can easily imagine what they must have looked like. Note the door opening in the background, for example.

Steps leading to the agora

Because the entire city is built across two mountain peaks, the sides have been terraced to facilitate construction. This large street leading up to a flat area used as the city’s agora, is stepped to make it easier to climb up. Be careful, however: the stones here are smooth and slippery!

Private cistern

This hole in the ground was used as a private cistern. Because Lato was located so high up in the mountains, water must have been a constant concern. Private cisterns like these were used to collect rainwater and to ensure that the inhabitants of the associated house had enough to drink.

A house

A view inside one of the structures in Lato that line the main street that connect the gate to the agora. This was presumably a house, or some kind of (work)shop. Note the use of the large stone blocks for the door frames.

The agora

This relatively large, flat area was used as the city’s agora, the meeting place. This was the ancient city’s civic heart. In the background you can see the steps that would have been used as seats. The low fence mark the boundaries of the city’s main cistern (see below). In front of it, to the south, are the remains of a temple; to the left, the remains of stoa.

The main cistern

This is a view inside the cistern, which the ancient Latians had dug into the agora.

The prytaneion

Along the northern edge of Lato’s agora is a structure identified as the prytaneion. This would have been the seat of Lato’s government, where the prytaneis gathered.

Exedra

This structure along the slope of the southern acropolis is located directly next to a large number of (badly preserved) seats. It is believed to have been a rectangular exedra, i.e. a rectangular building that was open to the north. It must have been part of the “Theatral Area”: from the stepped seats and the exedra, spectators would have been able to attend events that were organized on the open space in front of these features.

Temple

On the terrace above the Theatral Area are the remains of a large temple. This structure dates from the late fourth or early third century BC. It has a square naos and a rectangular antechamber on the east. Inside the naos or main space the base of the cult statue has been preserved in situ. If features an inscription that is sadly illegible. In front of the temple is a small altar, not visible in this picture.