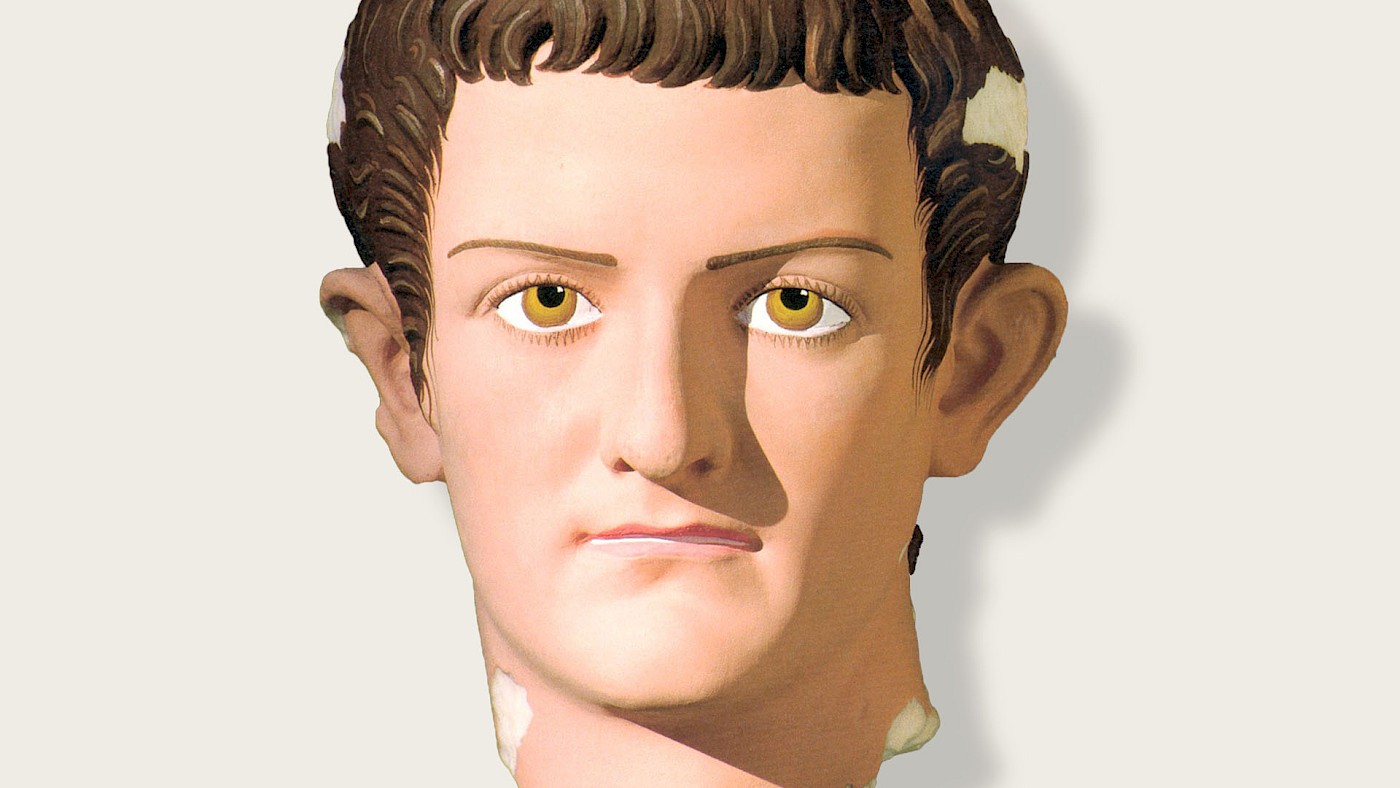

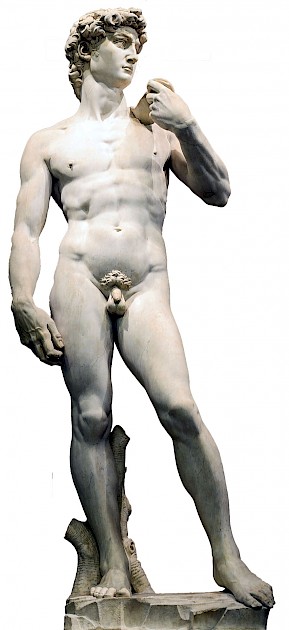

During the Renaissance, artists and scholars believed that the statues of the ancient Greeks and Romans had originally been unpainted. The white marble of the typical statue became an aesthetic ideal. When the Italian artist Michelangelo created his statue of David (1501-1504), he believed he was following Classical ideals in leaving the marble statue unpainted.

As John Boardman notes in his book Greek Sculpture: The Late Classical Period (1995, p. 11):

But they [i.e. modern observers and art historians] look mainly at sculptures in terms of mass and form, not of surface. We tend to resist admitting that Classical realism also embraced the way the figures were finished because none has survived in its pristine state, and our appreciation of the true Classical has been maimed by the Renaissance’s insistence on the plain white forms in which classical sculpture became known. There is every reason to think that a virtual trompe l’oeil effect was aimed at for lifesize figures, the heroic being only centimetres larger […].

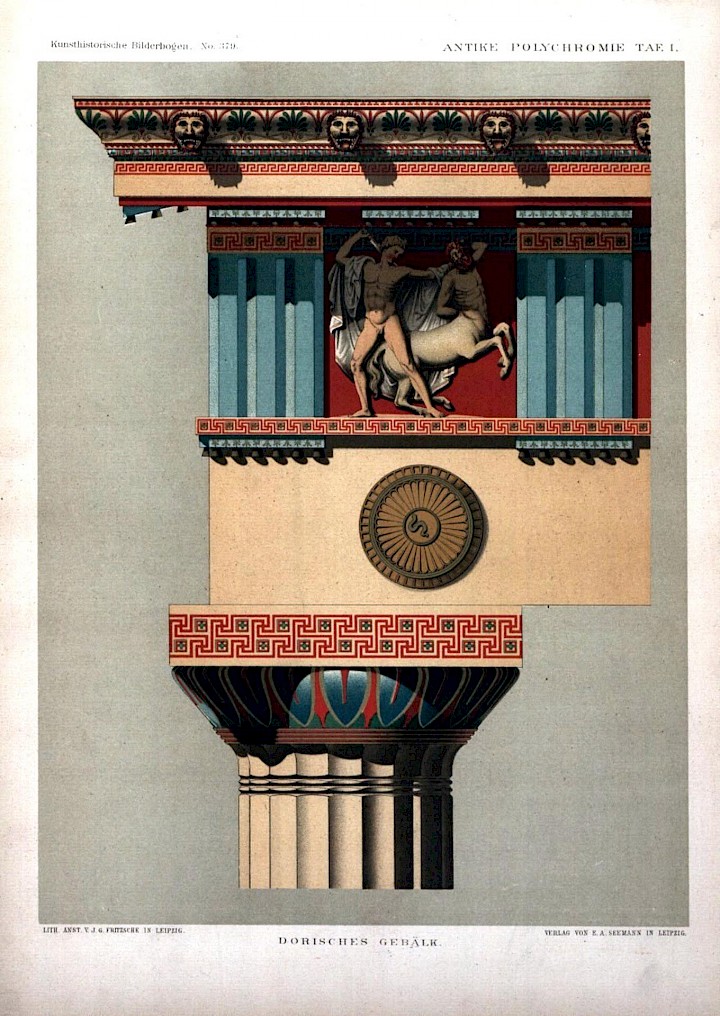

By the eighteenth century at least, scholars had discovered the remains of paint on ancient statues, such as specimens unearthed at Pompeii. In the nineteenth century, archaeology slowly developed as a discipline and large-scale excavations were being conducted in Italy and Greece, where it became increasingly clear that statues, reliefs, and other forms of sculpture were originally painted in bright colours.

Of course, not everyone accepted the idea that the ancient Greeks and Romans (among others!) had originally painted their marble statues. Between those who utterly denied the notion and those who embraced the fact that ancient statues had once been painted there was a third group of art historians and archaeologists, who argued that the statues had only been partially painted. The latter group proposed that the ancients only used a limited set of colours, too, like red and blue. (Not coincidentally, red and blue remain the most visible for the longest amount of time.)

Ancient polychromy

Nevertheless, it slowly became apparent that ancient sculpture, as well as architectural elements, had originally been painted in various colours. Modern investigative methods, using, for example, ultraviolet light or microscopic analysis, have shed much light on the colours used to decorate ancient sculptures, buildings, and more.

Ancient statues were painted to make them more lifelike. Metopes, friezes, and other sculptural elements located high up on temples were given bright red and blue backgrounds so that the scenes, executed in relief and also painted in lifelike hues, would have been more readily visible when seen from the ground.

We are well informed as regards the colours used to create paints in ancient times, thanks for example to the writer Pliny the Elder. In his Natural History, Pliny spends quite some time writing about stones and metals, and which materials were used in the creation of statues, wall-paintings, and more (books 33 through 37).

Ancient paints were made largely by grinding up minerals such as azurite, gold and red ochre, realgar (a toxic arsenic sulfide), vermillion (referred to as “dragon’s blood”), hematite, malachite, Egyptian blue (i.e. calcium copper silicate), and orpiment. The most common colours were therefore various shades of blue, green, red, and orange/yellow. Black was created using charcoal.

The pigments were often mixed with egg yoke or hot wax to create the actual paint. Depending on the size of the crystals of the pigments, the paint sometimes had to be applied in thick layers, making them more easily susceptable to flaking and loss. Painted statues and buildings would no doubt have needed to be touched up regularly.

Marble wasn’t the only material that would have been painted over. Terracotta statues, as used by both the Greeks and especially the Etruscans, would have been painted, too. The same naturally applies to ancient wooden statues. In some cases, different materials were used for different effects: a pair of marble hands and a head could be attached to a wooden body, probably because the marble, when painted, looked similar to human skin.

Perhaps surprisingly, bronze statues also had colours applied to them. While the bronze “skin” of a statue would have been left unpainted, probably because it at least approximates the skin colour of a tanned person living in the Mediterranean, colours were used for other parts of the body and for clothing. Eyes and teeth were often inlaid and hair was made darker; gold leaf could be applied to highlight other parts of a statue’s body or dress.

Clothing could easily be painted onto a statue. Indeed, there are some statues that appear to be naked, but actually had clothing, and even armour, painted on. In other instances, a statue might have been given actual clothes to wear in order to obscure the figure’s nudity. Weapons and armour were also sometimes made out of bronze or iron and added to a statue. Of course, many statues actually did depict naked figures, but we should expect the marble skin to have been painted in realistic hues.

Closing thoughts

This article only scratched the surface regarding ancient polychromy. But perhaps next time you’re in a museum, looking at another pale, Greek, Etruscan, or Roman statue, or a relief, remember that the object in question must once have been painted in bright colours. The ancient artists intended for their work to be lifelike, and colour was an important element in realizing that ambition.

Further reading

- J. Boardman, Greek Sculpture: The Late Classical Period (1995).

- S. Bond, “Why we need to start seeing the Classical world in color”, published at Hyperallergic.com (7 June 2017; accessed 28 December 2017).

- V. Brinkman, H. Brijder et al., Kleur! bij de Grieken en Etrusken (2005).

- V. Brinkman, Renée Dreyfus et al., Gods in Colour: Polychromy in the Ancient World (2017).

- R. Osborne, Archaic and Classical Greek Art (1998).