The symposium or drinking party, during which the participants reclined on couches, is a key element of Classical Greek culture. Of course, Greeks had organized parties before. But in, for example, the epic poems Iliad and Odyssey, attributed to Homer (ca. 700 BC), the Greeks ate and drank while sitting in chairs (Hom, Il. 215-225), rather than reclining.

Fundamental aspects of symposia, such as the act of reclining, were cultural elements that had been adopted from the East, most likely via Asia Minor. But the origin of reclining on couches may well be sought further afield. There are, for example, close parallels between Greek depictions of men reclining on couches and Assyrian art of the seventh century BCE (Topper 2009).

The act of reclining on couches was introduced over the course of the Archaic period (ca. 800 to 500 BC), starting in the seventh century BC, also referred to, tellingly, as the “Orientalising” period, because many elements from Asia are introduced into Greek art and everyday life, including furniture that is clearly inspired by examples from Southwest Asia.

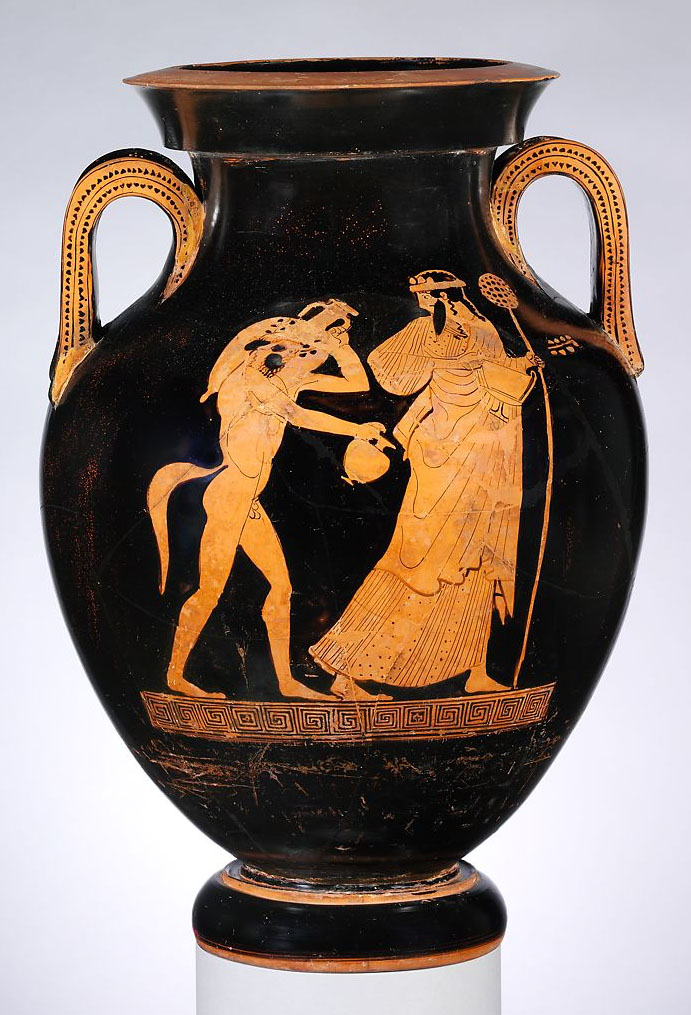

Schmitt-Pantel (in Murray 1990) identified sympotic-style gatherings from the Archaic age as “reclining banquets”. However, there are over 200 Late Archaic and Early Classical Athenian vases, so dated to ca. 525-475 BC, that feature scenes of symposia that lack the characteristic klinai (reclining couches). These primitive symposia suggests a development from the Archaic sympotic-style gatherings into what can be recognised as the Classical symposium.

Reclining at symposia was, of course, not exclusive to Athens, but common practice across all Greek poleis. Excavations at the Sanctuary of Demeter and Korē in Corinth uncovered several dining rooms with couches that date to the fifth century BC (Bookidis and Fisher 1972). It is similar to a structure unearthed at Brauron in Attica that includes nine rooms, each with eleven couches. The couches are situated along the walls of the room on both sites in Corinth and Brauron.

In a previous article, I sought to discover why someone, particularly an Athenian, might want to go to a symposium. I explored what was on offer at symposia, such as alcohol, a range of food, various forms of entertainment, but also how the symposium provided a platform for the host – as well as attendees – to show off. That article ended on what was a brief overview of the logos sympotikos, which was another platform by which a symposiast could attempt to flaunt their knowledge and oratory skill.

Philosophy and politics

The logos sympotikos was a particular kind of drinking session which entailed a competitive and cultural conversation between symposiasts. Politics was one of these conversational topics that was openly discussed by symposiasts and passionate debates regarding elections could have an impact in Athenian society.

For example, the oligarchic revolts of 411 BC are said to have been spurred by deliberations within symposia, if we believe Thucydides (8.54). Symposia were important to ambitious Athenians as they offered them an avenue to achieve political notoriety and expand their power base by gaining influential friends.

Philosophical prose and oratory rituals were key features of the logos sympotikos. Philosophers chose to set their dialogues on love at symposia, suggesting that these topics were appropriate for this context. Socrates is recognised for his philosophical sagacity in the – fictional or at least fictionalised – dialogues written by Plato and Xenophon.

Socrates’ ability to make an argument and use analogies to support his ideas was a demonstration of his knowledge (Pl. Symp. 201a-207a). Comparable to political prowess and battlefield bravery, philosophical prose was greatly admired by affluent Greeks (Pl. Symp. 198a). Where symposiasts exhibited their oratory skill through performance, they engaged in a cultural expression which demonstrated a deeper understanding of their own cultural identity.

However, it should be noted that Socrates’ victory in Plato’s Symposium is ultimately owed to his ability to outdrink the other symposiasts (Saxonhouse 1995)! This suggests that the idea of the logos sympotikos as being centred on sophisticated conversation is perhaps not completely accurate as far as the reality of the “typical” symposium is concerned.

Taking turns to talk

Although symposia were fundamentally drinking parties, they also provided a climate for the continuation and maintenance of educational experiences and served as an integral part of the Athenian aristocratic lifestyle. Athenians could engage in both politics and philosophy, and it was in many ways a form of education that built on earlier experiences of attending a gymnasium.

Though originally a place of exercise, in the fourth century BC, gymnasia developed into educational institutions particularly associated with philosophy. Access to the gymnasium was offered only to those who were of citizen age, i.e. 18 years or older, and wealthy enough to afford tutorship. These educational institutions acted as a mechanism for social conditioning, allowing for the continuation of reciprocal competitive attitudes and good sport that was at the heart of Athenian culture, or at least its upper echelons.

Attending these institutions provided the wealthier classes of Athenian society the benefit of networking and the potential for social advancement. However, social mobility entailed potential repercussions, where even those attempting to climb the political ladder could as easily see themselves ostracised if the majority of citizens disliked their ambitions. Citizens would cast their votes using ostraka (pot sherds), on which they wrote down the names of candidates that they wished expelled.

Of course, there were also other places where fortunate Greeks could enjoy some education. There were private schools, although affluent families could also hire teachers. Greek society was patriarchal and fathers no doubt took a special interest in the education of their sons. In Xenophon’s Symposium (3.5), for example, Niceratus says:

My father was anxious to see me develop into a good man so he made me memorise the whole of Homer and so even now I can repeat the whole of the Iliad and the Odyssey by heart.

Just as they had been taught in the gymnasia, men took turns at the symposium to speak in an orderly fashion, one after another, offering suggestions as to what subject they should talk about (Pl, Symp. 177d):

I propose that each of us should make the finest speech he can in praise of love, and then pass the topic on to the one on his right.

This system of taking turns to speak allowed for everyone to contribute to the group. Furthermore, participants could embrace a cultural identity through reflecting on their experiences and engaging with each other’s views.

Naturally, Plato’s Symposium is far from the typical debaucherous drinking party that we might expect. His account presents the symposiasts as being on their best behaviour, with the ability to engage in high-minded conversations despite drinking alcohol throughout the night.

Music and praise

The symposium also offered a way to become familiar with the customs of non-Athenians. In Xenophon’s Symposium, a metic (resident foreigner), referred to only as “the Syracusan”, joins the party. The reason for this character’s anonymity is not known for certain, but it has been speculated that the Syracusan was actually Xenophon himself. Leo Strauss (1972) believed that the Syracusan was the same person as “Themistogenēs of Syracuse”, which has been accepted as a pseudonym for Xenophon.

However, Xenophon’s Symposium is set in 422 BC. This would mean that Xenophon, having been born around 430 BC, would have been too young to attend. It is therefore unlikely that the Syracusan from the Symposium and Xenophon are the same person. Given that this socratic dialogue is fictitious, the Syracusan entertainer may have just been invented; however, it still offers an interesting perspective and an insight into what went on at a symposium.

In any event, the text makes clear that the Syracusian is wealthy, bringing in his own troupe as entertainment (Xen., Symp 2.1). His entourage included a flute-girl, an acrobat, and a male exotic dancer. The symposiasts appear to have admired these entertaining dancers, and were even encouraged to learn some of their choreography. This willingness to engage with foreign cultures suggests an openness toward experiencing something different.

Musicians, in particular the flute-girls (aulētrides), were a traditional element of the symposium. They were present during the feasting and drinking, but were dismissed when the logos sympotikos began. The synergy between wine and aulos player is portrayed in both sympotic pottery as well as textual evidence (Goldman 2015).

After the feast, libations were poured in honour of the gods. The participants engaged in conversations that naturally included religious topics. All speeches in both Plato’s Symposium and Xenophon’s Symposium were offered in praise of the Greek god Eros (Xen., Symp. 1.10).

Indeed, religious rituals were an important aspect of Athenian life and it was common for aristocratic citizens to host symposia in celebration of certain religious festivals (Andoc. 1.16). Of course, the god most revered within symposia was Dionysos, the god of the vine.

According to Plato, when Alcibiades joined Agathon’s symposium he was dressed up to resemble Dionysos – wearing an ivory garland and ribbons on his head. He was also, fittingly, intoxicated (Pl. Symp. 212e). The same accoutrements used to depict Dionysos are also referenced in Euripides’ Cyclops and can be found in figurative scenes on sympotic pottery.

Closing remarks

The symposium was a drinking session that offered a range of cultural activities, which included taking part in a competitive, albeit intoxicated, conversation and a continuity of aristocratic traditions, which had roots that stretched back to the Archaic period. Elements were also adopted from Eastern practices.

In developing a cultural awareness through engaging with these sympotic rituals, wealthy Athenians, as individuals, unwittingly contributed to, and reinforced, the cultural development of Athens.

Further reading

- N. Bookidis and J. Fisher, “Thesanctuary of Demeter and Kore on Acrocorinth: preliminary report IV:1969-1970”, Hesperia 41.3 (1972), pp. 283-31.

- M.L. Goldman, “Associating the aulêtris: flute girls and prostitutes in the Classical Greek symposium”, Helios, 2.1 (2015) pp. 29-60.

- O. Murray, “The affair of the mysteries: democracy and the drinking group”, in: O. Murray (ed.), SYMPOTICA (1990), pp. 149-162.

- A.W. Saxonhouse, Fear of Diversity: The Birth of Political Science in Ancient Greek Thought (1995).

- P. Schmitt-Pantel, “Sacrificial meal and symposion: two models of civic institutions in the Archaic city?”, in: O. Murray (ed.), SYMPOTICA (1990), pp. 14-37.

- L. Strauss, Xenophon’s Socrates (1972).

- K. Topper, “Primitive life and the construction of the sympotic past in Athenian vase painting”, American Journal of Archaeology 113.1 (2009), pp. 3-26.