The Allard Pierson in Amsterdam, which houses the collections of the University of Amsterdam, possesses numerous plaster casts of ancient sculptures and reliefs. A few of these are currently on display.

These plaster casts were all made more than a century ago. In some instances, these casts are actually more complete than many of the original sculptures and reliefs that were left outside and had to weather acid rain and other corrosive effects of pollution.

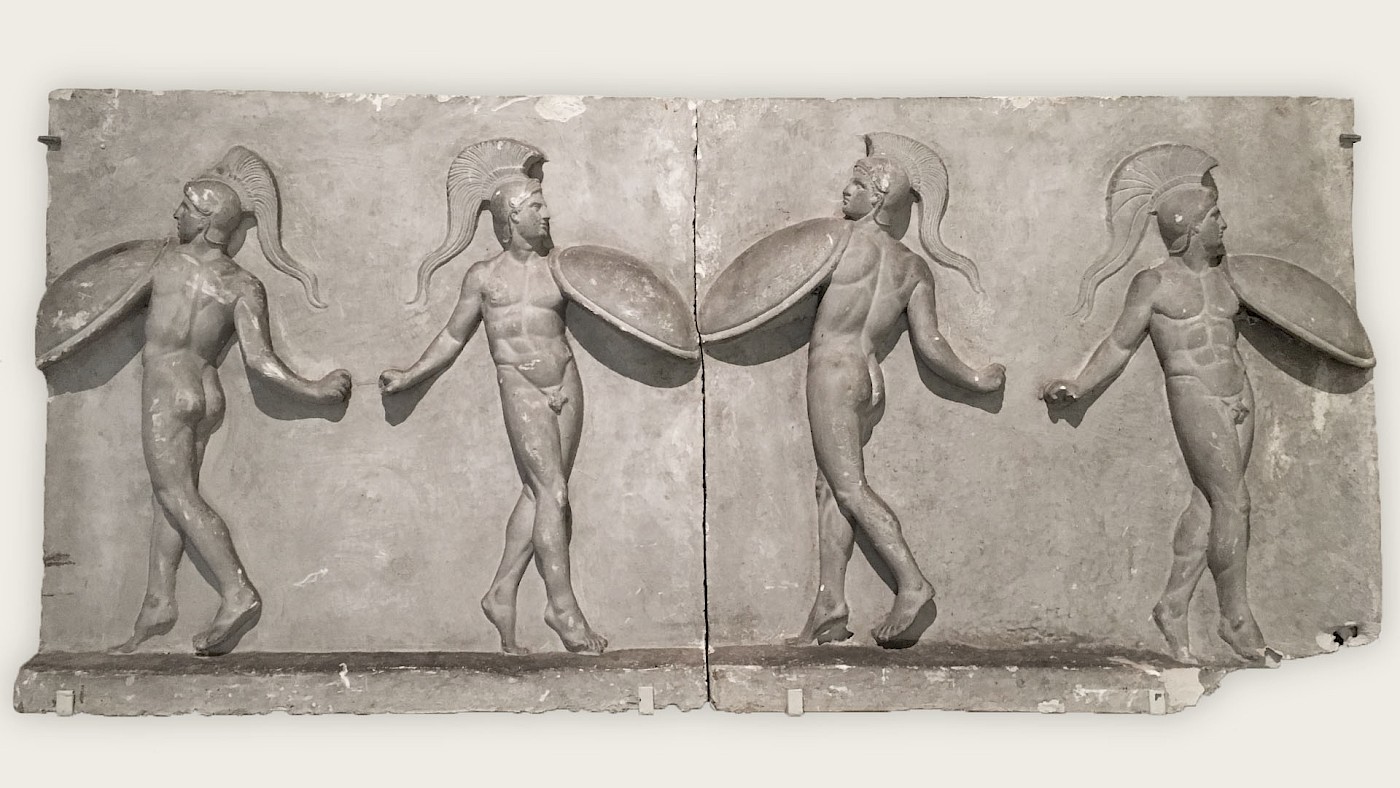

Dancing the Pyrrhic

The plaster cast used as this article’s featured image depicts a group of four dancing warriors. They are depicted naked, which in this case is no doubt due to the fact that the men are performing, like athletes in a contest.

The warriors are equipped with so-called Attic helmets that feature large crests. In real life, such crests would have been made of horsehair. They also carry an Argive shield on their left arms, the typical protection worn by ancient Greek hoplites.

This dance in armour is known as the “Pyrrhic” and was perhaps, as the relief’s descriptive plaque suggests, of Cretan origin. During the dance, the men moved around and would rhythmically beat the shields of their neighbours, perhaps in a kind of mock battle. The swords are not shown in the relief; perhaps these were originally made of metal and placed in the right fist of each individual.

The original relief is currently in the Museo Pio-Clementino, one of the Vatican museums (inv. no. 321). The museum suggests that the relief was probably made in Athens and that the dance was part of the Panathenaea, one of the main religious festivals in the city. The relief dates from the first century BC, but is probably a copy of an earlier relief dated to ca. 325 BC based on style.

Perhaps you’re wondering how one can date a Greek relief on style? Without going into too much detail, as a very general rule, the deeper the figures are cut into the stone, the more recent the reliefs tend to be. The details of the anatomy and, in this case, the equipment shown, can help narrow down the date even further. Based on these criteria, a date of ca. 325 BC seems like a reasonable guess.

The point of this article is that plaster casts are useful: they cannot just be used as a study aid for students, but can also introduce visitors to objects that they might otherwise never be able to see up close. While there’s perhaps no substitute for original objects, plaster casts are a fairly inexpensive and equitable way to share the ancient world with a museum’s visitors, and they are also useful objects of study for students.