The existence of what is now referred to by some as the “Dark Age” of Greece became apparent to modern scholarship in the nineteenth century CE. Originally conceived as a lapse in time between the “heroic” age of Homeric myth and the beginning of the historical era represented by the lyric poetry of Alkaios and Tyrtaios, the synchronisation of the fall of the Mycenaean Palaces with Egypt’s Nineteenth Dynasty revealed a significant gap between the destruction of the Mycenaean Palaces, ca. 1200 BCE, and the conventional dates of the early poets, ca. 700 BCE (Kotsonas 2016, p. 241).

Various terms were used to define this “gap”, including the Greek Middle Ages and Dark Age, while studies of the pottery of this period gave us the ceramic phases Sub-Mycenaean, Protogeometric, and Geometric. Increasing archaeological evidence for this period over the course of the twentieth century led to the major studies by Vincent Desborough, Anthony Snodgrass, and Nicholas Coldstream in the 1960s and 1970s; study of the period has only escalated in the half-century since (Murray 2018, pp. 18-19).

The increasing popularity of the period, now more generally called the Early Iron Age by specialists, has tended to obscure the fact that the calendar dates assigned to its internal phases rest on shaky ground. The absence of datable historical events means that there are limited fixed points onto which to hang the pottery phases that make up its relative chronology. Even as archaeological evidence from the period increases in quantity, our understanding of its chronology still rests on chance finds of Greek pottery in the destruction levels of Near Eastern settlements, where historical calendar dates are more readily available from written texts.

New evidence from Sindos in Central Macedonia, Greece, may change this picture (Gimatzidis and Weninger 2020). Excavated in the 1990s to early 2000s by the Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, led by Prof. M. Tiverios, the dating of the site has received great attention in its publication. Sindos is a tell – an artificial mound created by successive use of a location that is destroyed or rebuilt on top of the debris of the earlier habitation, which preserves assemblages of objects within layers extremely well.

Sindos was occupied from the Bronze Age through the Early Iron Age and into the Archaic Period. This region was once considered peripheral, but it is now apparent that there were strong connections to the central Aegean, especially Euboea, reflected in the pottery discovered in the increasing number of known Early Iron Age settlements in Central Macedonia and the nearby Chalkidike, including Torone and Assiros.

The sequence of occupation, connections to the wider Aegean world, and the excavation of well-preserved contexts allowed the excavators at Sindos a unique opportunity to test the chronology of Early Iron Age Greece. Taking samples of animal bones from six successive layers, the excavators were able to get reliable radiocarbon dates for contexts that were firmly attached to the pottery phases of much of the Early Iron Age. The results suggest that this period may have been much longer than was previously understood.

In this series of articles, I will look at how the chronology of EIA Greece has been built in the past; what the evidence from Sindos suggests about the absolute dating; and the consequences of accepting these dates on our understanding of the early development of Greece after the collapse of the Mycenaean Palaces.

Stratigraphic chronology

In order to understand the impact of the Sindos radiocarbon dates, we must first understand how the chronology of the Early Iron Age has been established and is understood. In order to do that, we must also look at the ways in which archaeological chronologies are established in general.

There are two broad categories of dating methods in use in archaeology. First of all, there is relative chronology: the sequence in which things happened; which things are older or younger compared to other things. Secondly, there is absolute chronology, the actual calendar dates at which things happened, sometimes within a range of years. The absolute chronology will be the subject in the second of this series of articles.

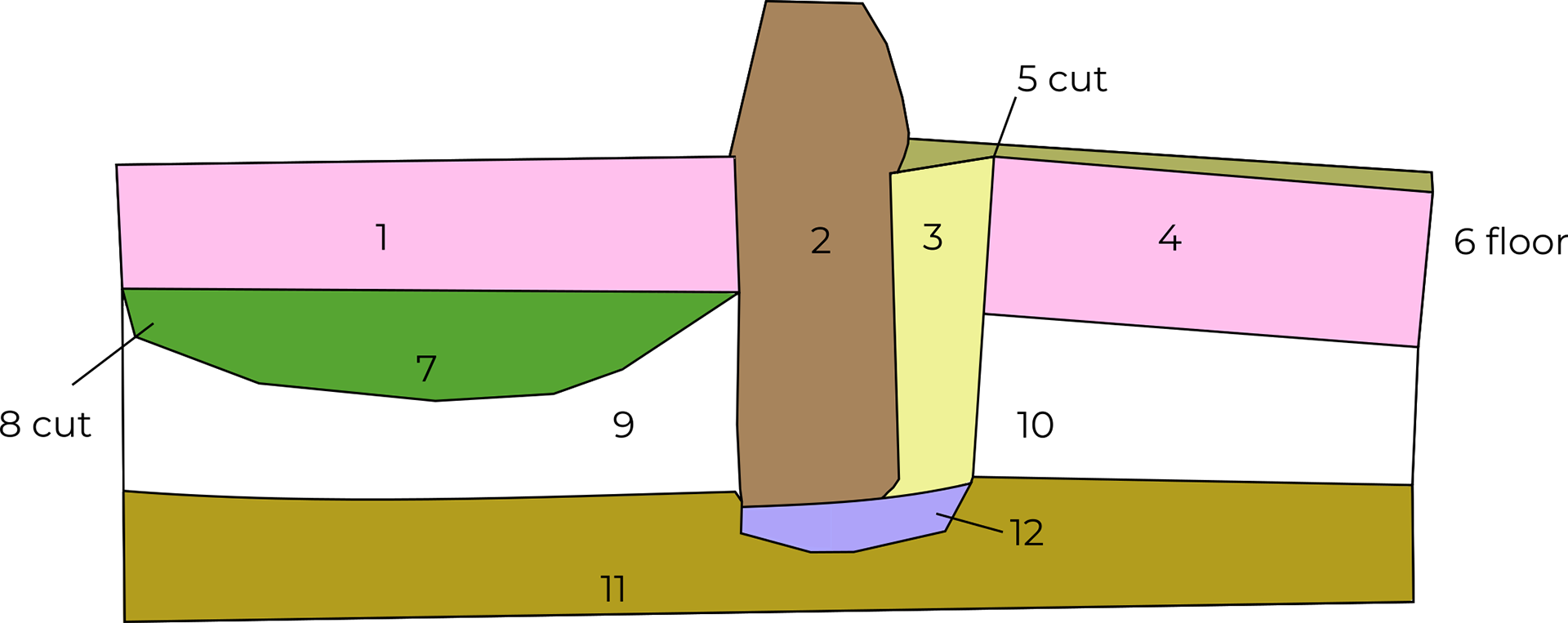

Relative chronology is typically established in two ways. First there is the stratigraphic sequence of excavations – i.e. which excavated layers or strata are above and below one another. Typically, each stratum represents a period of use in succession going back in time from the present surface or topsoil to the natural earth or bedrock at the bottom.

Stratigraphy is not always simple. Certain kinds of sites – such as cemeteries – are not always obviously stratified. Even in stratified sites, human, animal, and plant activity can disturb the sequence: previous activity can be entirely cleared away for reconstruction; pits can be dug in which later objects will appear lower than earlier ones; animals can burrow through layers to form their homes. These activities are also interesting to most archaeologists, and understanding how deposits are made is integral to our understanding of stratigraphy.

The best-preserved phase will always be the latest, although it does not follow that more recent occupation survives better than earlier occupation in general. At Xeropolis-Lefkandi in Euboea, the Late Geometric settlement and post-palatial Mycenaean settlements are far better preserved that the intermediate Early Iron Age phases in part because the last phase of construction destroyed the preceding habitation layers more thoroughly than the previous Iron Age settlement damaged that of the post-palatial Mycenaean.

Stratigraphy alone can’t answer our questions about human activity throughout time; for that, we must look at the assemblages of artifacts within strata. Nevertheless, stratigraphy is the fundamental basis of archaeological chronology.

Typological chronology

The second kind of relative chronology is the typological sequence of artifacts. The advantage of typology is that it can be applied broadly across sites with similar material culture and in particular those which were in contact with one another and exchanged artifacts. The basic principles of typology are that the style of artifacts changes over time and that objects of the same class (swords, fibulae) produced around the same time are likely to be more similar to one another than to those produced centuries later.

The relative chronology of the Early Iron Age has typically relied on the use of typological pottery phases (see Table 1). Pottery is a useful medium for the establishment of a chronology because it is at once fragile and durable: it breaks easily, but into sherds that will last millennia. Its fragility means that it is produced in vast quantities throughout much of human history, and its durability means that the remains of these vessels litter archaeological strata. Furthermore, when pottery is painted its style of decoration changes more rapidly than its shape, which is more functional, thus creating more notable changes over time.

| Phase | Conventional dates (BCE) | Noteworthy events |

|---|---|---|

| Late Helladic IIIC | 1200-1075/1050 | Griffin Alabastron, Lefkandi Destruction of Koukounares, Paros |

| Sub-Mycenaean | 1075/1050-1025 | |

| Early Protogeometric | 1050/1025-1000 | Foundation of the Sanctuary at Olympia |

| Middle Protogeometric | 1000-950 | Building at Toumba, Lefkandi Confronted archers from Skoubris, Lefkandi |

| Late Protogeometric | 950-900 | Lefkandi Centaur |

| Sub-Protogeometric (Euboean) | 900-760 | “Warrior-Trader” at Lefkandi-Toumba |

| Early Geometric (Athenian) | 900-850 | |

| Middle Geometric (Athenian) | 850-760 | Tomb of the Rich Athenian Lady |

| Late Geometric | 760-700 | Nestor’s Cup, Pithekoussai Destruction of Asine Abandonment of Zagora Paros Polyandrion |

The pottery chronology of Early Iron Age Greece has been heavily studied and is well known, as is that of the preceding Bronze Age. A key difference is that in the Mycenaean palatial period there was an overarching homogeneity of pottery style, which began to break down into regional styles in the post-palatial period, corresponding to the pottery phase Late Helladic IIIC.

Throughout the Early Iron Age there are a number of regional varieties in pottery sequence. The best known is the Athenian sequence, established from the excavations of the Kerameikos cemeteries and refined by those of the Agora. The Athenian pottery sequence gives us the broad phases Sub-Mycenaean, Protogeometric, and Geometric, the latter two of which are divided into Early, Middle, and Late phases.

Two regions offer illustrative varieties in the stylistic chronologies of their pottery. The Aegean island Euboea, where the important Early Iron Age sites Lefkandi and Eretria are located, and various connected regions follow a different, more conservative trajectory in its pottery style from the end of the Protogeometric Period. This style is known as the Sub-Protogeometric, which is divided into three sub-phases numbered I, II, and III. These correspond to the Early and Middle Geometric Phases in Athens.

Crete also has its own pottery sequence, and one that deviates from the Athenian significantly. Following the Late Minoan IIIC style, contemporary with Late Helladic IIIC, Crete has a long Sub-Minoan style that is contemporary with the Athenian Early and Middle Protogeometric phases. The Cretan Protogeometric is then aligned more closely with the Late Protogeometric and Early and Middle Geometric phases of Athens; its Early and Middle Geometric with Athenian Middle Geometric. However, the Cretan sequence can also vary widely from site to site across the island.

By the Late Geometric Period there is a kind of homogeneity in Greek pottery style, following the lead of Athens. This breaks down in the following phases as Corinth in particular begins to incorporate ideas from the Near East and Egypt in their pottery, in the style we call Proto-Corinthian.

The most controversial element of the Early Iron Age pottery chronology is the so-called Sub-Mycenaean Period. First used to describe the pottery from a cemetery on Salamis excavated in the late nineteenth century CE, the term Sub-Mycenaean was popularised by its use to describe similar pottery from the excavations of the Pompeion cemetery of the Kerameikos in 1939. Sub-Mycenaean is the earliest phase of pottery known in the Kerameikos cemetery.

Vincent Desborough applied the term more broadly to a culture beyond pottery, including common elements such as single burial in pits, and the use of long pins, and arched fibulae. He considered the period to be regional, incorporating Athens, Salamis, and Lefkandi, and contemporary with the final stages of Late Helladic IIIC pottery in other regions, such as the Argolid.

Theoretically, in the regions where it occurs the Sub-Mycenaean phase falls between Late Helladic IIIC Late and Early Protogeometric pottery styles. However, Sub-Mycenaean has always been defined by funerary assemblages. In settlement contexts, the evidence is meagre, and no deposits distinct from an earlier Late Helladic IIIC stratum and a later Early Protogeometric stratum have been discovered (Papadopoulos et al 2011, p. 194).

The case of Sub-Mycenaean indicates how stratigraphic and typological relative chronologies are not mutually exclusive. Typological sequences will, in part, be based on the stratigraphic sequence of settlements, which guide careful study of how the features of cultural artifacts change over time.

As much of the early evidence for the Early Iron Age came from graves, the typology of pottery has been the main basis of the relative chronology, with stratigraphic sequences providing supporting evidence. While stratified sites in central Greece are becoming more widely excavated and published, elements of the chronology are still dependent on the informed estimation of scholars based on the quantity and quality of the material, the number of graves in which a certain phase’s pottery is found, and, where possible, its association with a number of occupational strata.

End of part I

Relative chronology provides a sequence of events, telling us the order in which events happened and allowing us to look at how things changed over time. It provides an essential framework for understanding archaeological processes and the development of human societies.

What it cannot tell us with any certainty is how long these developments took, how they compare to processes in other sites, and how Early Iron Age Greece connects to sites that are more securely positioned with calendar dates. In order to ascribe calendar dates to these pottery phases, we need to look at methods of absolute dating, which will be the subject of the second article in this series.

Further reading

My discussion of relative and absolute dating in general is informed by Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn, Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice (Sixth edition, 2012), pp. 121-166. However, I also consulted Theo Nash’s 2018 blog on the Thera Eruption, which is an excellent look at the significance of relative and absolute chronology in the Bronze Age.

The three major studies of Early Iron Age Greece in the 1970s were:

- Anthony Snodgrass, The Dark Age of Greece: An Archaeological Survey of the Eleventh to the Eighth Centuries BC (1971, 2nd ed. 2000).

- Vincent Robin d’Arba Desborough, The Greek Dark Ages (1972).

- Nicholas Coldstream, Geometric Greece: 900-700 BC (1977, 2nd ed. 2003).

A recent summary of Early Iron Age pottery is available in:

- Walter Gauß and Floria Ruppenstein, “Pottery”, in: Irene S. Lemos and Antonis Kotsonas (eds), A Companion to the Archaeology of Early Greece and the Mediterranean (2020), pp. 433-470.

For the history of scholarship on Early Iron Age Greece:

- Antonis Kotsonas, “Politics of periodization and the archaeology of Early Greece”, American Journal of Archaeology 120.2 (2016), pp. 239-270.

- Sarah C Murray, “Lights and darks: data, labeling, and language in the history of scholarship on Early Greece”, Hesperia 87.1 (2018), pp. 17-54.

The Sub-Mycenaean Period:

- John K. Papadopoulos, Brian N. Damiata, and John M. Marson, “Once more with feeling: Jeremy Rutter’s plea for the abandonment of the term Submycenaean revisited,” in: Walter Gauß, Michael Lindblom, R. Angus K. Smith, and James C. Wright (eds), Our Cups Are Full: Pottery and Society in the Aegean Bronze Age: Papers presented to Jeremy B. Rutter on the occasion of his 65th birthday (2011), pp. 187-202.

The publication of the Sindos radiocarbon dates:

- Stephanos Gimatzidis and Bernhard Weninger, “Radiocarbon dating the Greek Protogeometric and Geometric periods: The evidence of Sindos”, PLoS ONE 15.5 (2020).