Pictorial vase painting is an important source of information for historians and archaeologists. Like literature, it represents a deliberate attempt on the part of the people of the ancient world to represent how they saw or imagined the world around them, whether as reality or through myth.

But although pictorial vase paintings are more difficult to “read” than texts, the vast quantities of pottery produced, the fragility of the vessels, and the durability of the material means that vast quantities of pottery survive, even if only a fraction of these are pictorial.

Non-pictorial vases of all kinds are, of course, significant to our understanding of the actions and behaviour of ancient people. Pictorial pottery gives us another perspective on their lives.

The not-quite pictureless hiatus

In the century following the collapse of the Mycenaean palaces, there is something of a revival in the fortunes of certain regions of the Aegean.

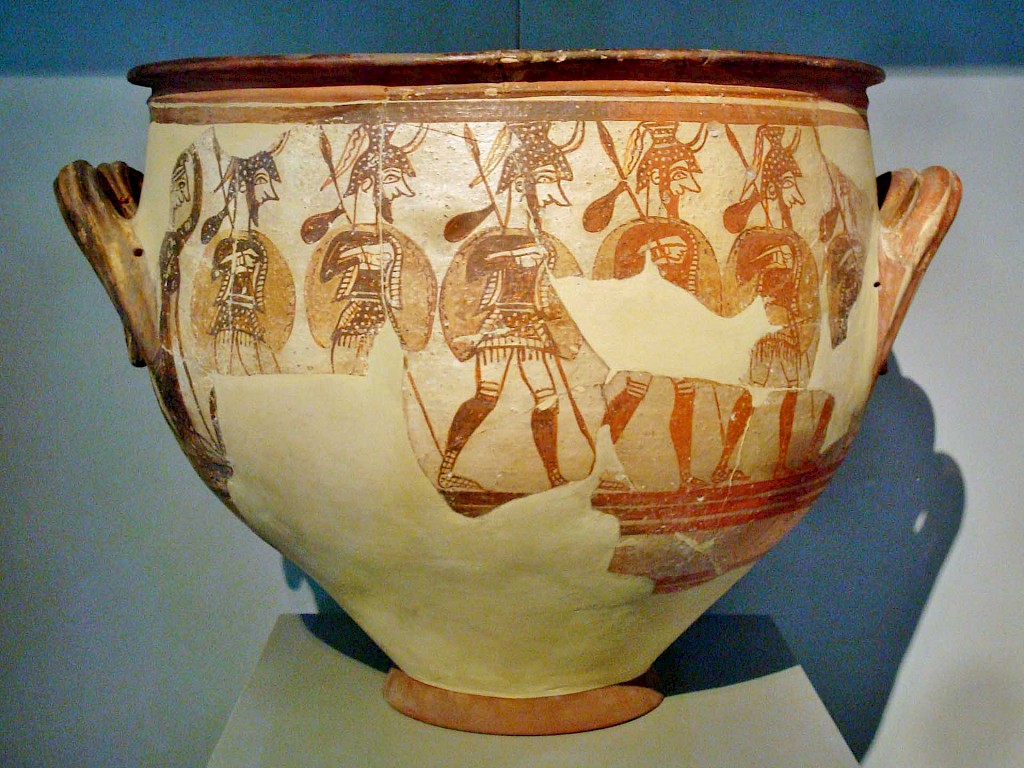

Corresponding to the pottery period Late Helladic IIIC Middle (ca. 1150-1000 BC), this revival included the production of striking pictorial pottery, the most famous example of which is the “Warrior Krater” from Mycenae.

But this revival does not seem to have lasted more than a generation or two. Pictorial decoration on pottery disappears in LH IIIC Late, and would not resurface on any great scale until the Athenian Late Geometric pottery of the eighth century BC.

This is not to say that the pottery of the Early Iron Age is by any means lacklustre. After the so-called “Submycenaean” pottery phase (a regional phenomenon, if it existed at all), central Greek regions such as Attica and Euboea began to decorate their pottery with geometric shapes using new technology such as the compass and the multiple brush.

For several centuries these geometric patterns of varying elaboration carried meanings that it is difficult for the modern archaeologist to interpret. Across much of the Aegean a decision had been made to no longer depict pictorial scenes on pottery, suggesting that the social circumstances in which it was useful or valuable have changed.

But pictorial decoration is not quite absent from the artistic repertoire of Early Iron Age Greece. Human and animal images persist throughout in the pottery from the cemeteries at Knossos on Crete, although they are not common. (For a detailed discussion of the pictorial pottery from this period, especially from Knossos, see J.N. Coldstream, “‘The long, pictureless hiatus’. Some thoughts on Greek figured art between Mycenaean pictorial and Attic Geometric”, in: Eva Rystedt and Berit Wells (eds), Pictorial Pursuits. Figurative Painting on Mycenaean and Geometric Pottery (2006), pp. 159-163.)

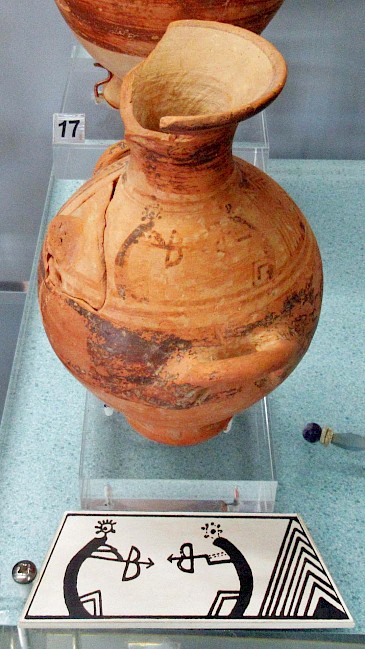

At Lefkandi, in the Middle Protogeometric pottery period (ca. 1000-950 BC) there are a variety of (almost) human images, both imported from the Near East and locally produced. Among these is a hydria showing two archers facing each other, bows drawn.

Confronted archers

The hydria was one of four Middle Protogeometric (ca. 1000-950 BC) vessels found in a cist grave (i.e. a stone-lined shaft) in the Skoubris cemetery. Stylistically, the archers seem to hark back to the Late Bronze Age pictorial in the shape of their heads; their double-arched bows, however, are far more similar to those depicted in later periods.

The excavators suggested that the image may have been inspired by chance finds of Late Bronze Age sherds on Xeropolis, the tell on which the Lefkandi settlement was located, although it is unclear why such discoveries would inspire so few imitations (Mervyn R. Popham and L.H. Sackett, Lefkandi I: The Iron Age (1980), p. 127).

The Skoubris cemetery is the earliest of the Iron Age cemeteries at Lefkandi, with the earliest graves known dating to the Submycenean pottery phase of the middle-eleventh century.

The building in the Toumba Cemetery in which the hero and heroine of Lefkandi were buried also dates to the Middle Protogeometric period; it is likely that the first half of the tenth century was a dynamic period in Lefkandi’s history.

Art and myth at Lefkandi?

It is possible that the so-called hero’s burial contains a hint as to why one particular artist chose to depict archers on a hydria. The cremated remains of this man were buried in a bronze vessel from Cyprus, already an antique by the time it was placed in the ground. Around the rim of this vessel were depicted archers hunting various animals. Given the significance of this burial, and the vessel itself, is it possible that the vase painter was copying this motif?

Against this interpretation, Irene Lemos has pointed out that the archers on the hydria don’t really resemble the Cypriot archers at all: the Lefkandiot archers do not wear helmets; their bows are the double-curved composite type against the single curved bow of the bronze urn. Furthermore, the graves at Lefkandi contain plenty of imported figurative objects from the Near East from the end of the eleventh century that aren’t copied. Lemos concludes: “I believe that this was not because they could not copy the images, but because they were not really interested in them” (Irene Lemos, “Songs for heroes: the lack of images in early Greece”, in: N. Keith Rutter and Brian A. Sparkes (eds), Word and Image in Ancient Greece (2000), pp. 11-21; quoted at p. 16).

Lefkandi, after all, had its own visual culture represented by figurines. Most notable is the Late Protogeometric Centaur, discovered broken and split between two graves in the Toumba cemetery. The Centaur is significant because certain features of its composition – the six fingers on its surviving hand and the gash in its front left leg – suggest that it depicts a particular mythological figure, specifically Chiron, the Centaur who trained Achilles (Lefkandi I, pp. 345-346).

In the Protogeometric Period Lefkandi appears to have already been engaging with mythological stories that would continue to be known in later Greece.

Does the hydria represent something similar? Unlike the Centaur, the scene of confronted archers does not contain any obvious hints to a particular myth, known or unknown. It seems unlikely that we could pin a particular story to this scene.

Concluding thoughts

The confronted archers on this hydria from Lefkandi raise interesting questions for our understanding of Early Iron Age society. It points to experiments in art that do not take off, and reminds us that absence of evidence can be the result of deliberate choices not to use certain modes of expression, rather than lack of ability.

A final thought goes to the poem that inspired the title of this piece: Archilochus fragment 3 (West), dated to the seventh century BC. In this poem, Archilochus attributes to the Euboeans a particular kind of warfare: fought at close-quarters, with swords, and few light-armed troops with slings and arrows. (I’ve noted in the past that Archilochus might be contrasting the warfare of the Euboeans to that of his home island, Paros, where light-armed troops are more prominent.)

It is possible that the Middle Protogeometric hydria points towards an earlier period in which archery was much more prominent in Euboea, lasting at least until the burial of the so-called Warrior Trader at Lefkandi in the middle of the ninth century (Subprotogeometric II). In certain regions of the Aegean, the Early Iron Age was a dynamic time throughout which much changed.