I recently saw Mad Max: Fury Road, directed and co-written by George Miller, the original creator of Mad Max. It’s probably the best action movie to have been released in a long time and even manages to be better, in my opinion, than Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981). But why write about Fury Road on a website dedicated to the ancient world?

The reason is that there are some elements of the movie that recall Homer’s Iliad that struck me while I was watching it. I initially figured it was probably just me and my fascination for all things Homer until I listened to Tom Chick on a recent QuarterToThree podcast. He, too, happened to draw similar parallels, and I figured it was worth delving into this topic in a bit more detail.

A wasteland epic

Like all of the Mad Max movies after the first one, Fury Road is set in a world that has been wracked by some unknown cataclysm. The cataclysm itself recalls the collapse of the Bronze-Age world in ca. 1200 BC, except that it was far more devastating, severely reducing the human population and bringing about great environmental changes: the seas dried up and most (all?) of the earth seems to have turned into a dry and dusty wasteland.

The complex societies that characterize our modern world have been replaced by simpler ones that are almost tribal in nature. A cult has sprung up around the acquisition and use of oil, with a specific focus on cars. In Fury Road, the people ruled by Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne, who also played the main bad guy in the original Mad Max) have an entire belief system centred around cars. When vehicles are not in use, their steering wheels are removed and placed on an altar; when Joe’s “war boys” pray, they lock their fingers together to make the shape of an eight-cylinder engine, and so forth.

There is something primal about the world depicted in Fury Road that is, I think, recognizable and appealing. It seems to delve deep into the human psyche, referring back to a simpler age (either real or imagined), when life was more hazardous and death seemingly lurked around every corner. It tickles the same part of the brain, I think, that also makes e.g. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s final confrontation with the alien invader in Predator (1987) recognizable despite the outlandish conceit of the film: we’ve grown up, after all, with stories about heroes slaying monsters (such as Heracles).

In Fury Road, the plot is simple. Max (Tom Hardy) is captured by Immortan Joe’s war boys. Shortly afterwards, Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) is sent out on a mission with a “war machine” (armoured lorry) and an escort. Suddenly, she alters course and drives into the desert. Immortan Joe becomes alarmed and goes into a room, where he had apparently kept a number of women as his “wives” to breed healthy babies. Furiosa has taken the women on the war machine and is now driving out to the “green” place where she originally came from, in hopes of starting a new life there.

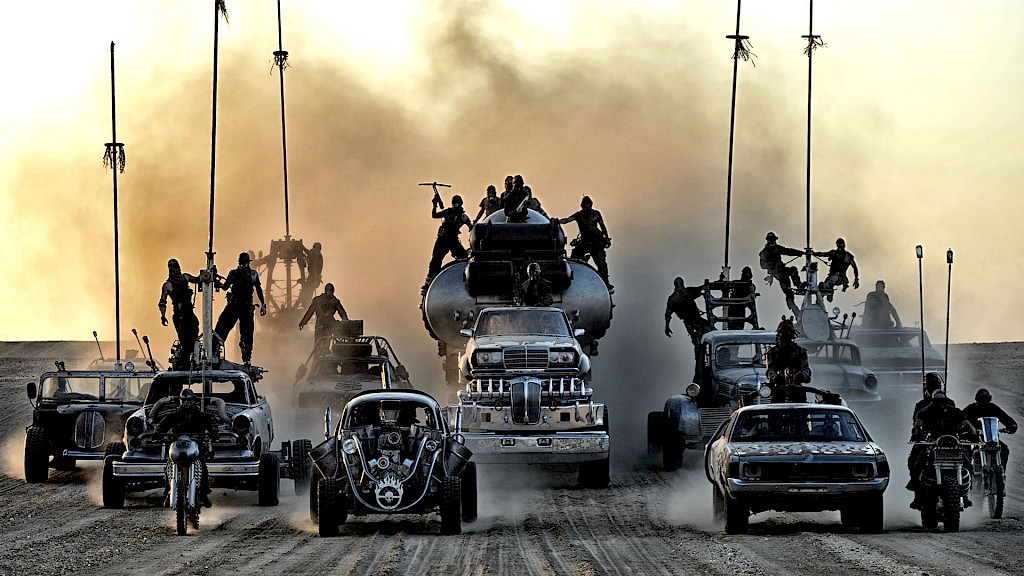

This is where the similarities with the Homeric epics and – more broadly – the Trojan War come in. The rest of the movie is essentially one long chase with on-road battles that recall much of the brutality and action of the Iliad, including characters that are briefly introduced and then dispatched in interesting ways. The vehicles recall chariots. Like the Iliad, there are a few points where the action is briefly interrupted to build characters and develop the plot.

Within the context of the movie, Furiosa’s “war machine” serves the same purpose as the city of Troy: a heavily armoured (fortified) thing that protects the people inside and that is frequently under siege. The main difference is that this fortress has wheels. In the movie, some of the most interesting fights take place on and around the war machine, with Joe’s war boys and other warriors assaulting the lorry in a manner reminiscent of the Greek forces assailing the walls of Troy.

But more in particular, the main cause for the movie’s plot – the taking of Immortan Joe’s wives – recalls the taking of Menelaus’ wife Helen by the Trojan prince Paris. Like Menelaus, Joe doesn’t just assemble his own army to pursue Furiosa. Instead, he calls for assistance from his neighbours at the Bullet Farm and at Gas Town. Dutifully, the rulers of the latter two places assemble their own forces and join the army of Immortan Joe for a chase down the Fury Road.

I have no idea if George Miller deliberately took inspiration from the story of the Trojan War. But one line of dialogue is interesting. At a certain point, the Bullet Farmer (Richard Carter) mutters, “All this over a family squabble.” It’s a sentiment that most of us will have had when reading something about the Trojan War: one man stole another man’s wife (or wives, as the case may be!), and this has caused an entire war to break out.

Mad Max: Fury Road is a great movie. Despite being limited in scope, it feels epic in how the action unfolds, and this is perhaps no doubt due in small part to it appealing – consciously or not – to some part deep in our psyche. I was reminded frequently of things that I had read in Jonathan Gottschall’s The Rape of Troy: Evolution, Violence, and the World of Homer (2008), which looks at the story of the Trojan War from a biological point of view. I think that Fury Road – like the Iliad and other great stories – appeals to us because it is so fundamentally human.

Addendum

An anonymous commenter to an earlier version of this article (published elsewhere) correctly pointed out that Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981) also has a number of Homeric traits, deliberate or not.

There is some role-reversal here, since in the movie it’s the defenders rather than the aggressors who win the war using a ruse (the tanker full of dirt). Fuel also takes the place of the kidnapped Spartan queen.

The rest of the movie maps more directly unto the Trojan War. The bikers are clearly meant to be the Greeks. They sacrifice captives on the mountain and feature a mohawked “Achilles” who vows revenge after his blond “Patroclus” is killed with a steel boomerang.