As archaeologists and historians, we’re often so focused on our own period or subject that we can forget that others exist. When I go to a museum in Greece, the first place that I will usually want to see is the prehistoric section. This means that I often miss exciting and interesting pieces from later periods and that these often don’t stick in my memory. On the other hand, because my focus is on a period that produces fewer spectacular finds and monuments, I am used to looking in obscure corners to find my interests.

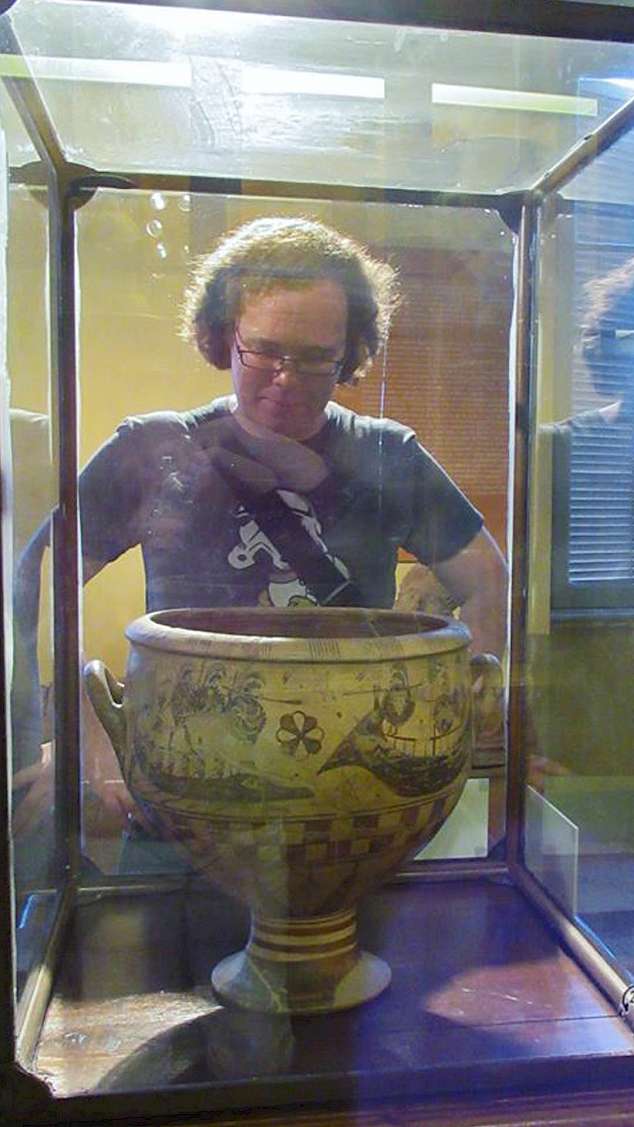

When I travel with my spouse, who is also an archaeologist but whose specialism is even earlier than mine, I am encouraged to focus on other aspects of the places that we visit, particularly when she gets annoyed at yet more Greek vases/sculpture. Fortunately, our last trip to the Mediterranean was to Rome, where (a) I had been before and (b) there is very little Early Iron Age Greek material (although I did stop to peak at the Aristonothos Vase in the Capitoline Museum, obviously).

We did visit the sites, but I didn’t need to insist on anything and it was on her initiative that we went to the Colosseum – after all, I thought that I’d seen it all before. The Colosseum is an impressive building, but I thought it was genuinely just an amphitheatre on a massive scale.

I was, of course, completely wrong.

The Colosseum

The Colosseum was built under the Roman Emperors Vespasian and Titus from AD 72 to 80. It is the largest known amphitheatre – that is, a theatre in the round, in this case oval. It was originally known as the Amphitheatrum Flavium (Flavian Ampitheatre) after the dynasty under which it was constructed; the name “Colosseum” is believed to have been derived from the colossal statue of Nero nearby.

The building of the Colosseum was funded by the spoils taken from the Second Temple in Jerusalem after the Roman defeat of the Great Jewish Revolt. Jewish slaves were among the massive construction force. However, the Colosseum is more widely recognised for the persecution of another religious group, the early Christians.

While the historical accuracy of these claims are disputed – the Circus Maximus, on the other side of the Palatine, is mentioned in ancient sources as the location of these martyrdoms – the Christian martyrs have been commemorated on site for hundreds of years. Nevertheless, the Colosseum was certainly the location of gladiatorial games and executions until it fell into disuse in the sixth century AD.

In the modern day, the Colosseum is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Rome.

A tourist

I first visited Rome in April 2006 and the Colosseum was our first port-of-call (it turned out entry was free that day, which was a bonus). I had just finished my first exams (taken after the fifth term for Classics undergraduates for some, presumably archaic, reason). We looked around, quoted Gladiator, and then moved on to the Forum. So far, so touristy.

This summer, my spouse and I approached the Colosseum from the opposite direction, first visiting the Capitoline Museum, then travelling through the Forum, before finally reaching the massive amphitheatre. Perhaps it was my age, or that it’s just a more recent memory, but we did spend longer looking at these sites than I recall having done previously.

On both occasions, the Colosseum had an exhibition in the upper gallery. I can’t remember the theme from 2006 – I have pictures of busts of Euripides and Epicurus, the Sappho fresco from Pompeii (presumably a copy?), and numerous red-figure vases. I remember walking over to my companion – not a Classicist – and giving the date and provenance of the vase at which he was looking without glancing at the label, as undergraduates in ancient art history are wont to do. The theme was clearly theatrical, in part, but there were other themes too.

After the fall

In 2017, the theme was much more memorable: the history of the Colosseum after the fall of Rome. Abandoned for centuries, an entire ecosystem developed within the amphitheatre, each arch forming an independent biosphere. Novelist and researcher Paul Cooper discussed this aspect of the Colosseum in a fascinating Twitter thread focusing on the botanist Richard Deakin, who investigated the plants growing in the ruins in the middle of the nineteenth century. He presents paintings and literary accounts of the Colosseum from the centuries before it was ever excavated, before it became a monument.

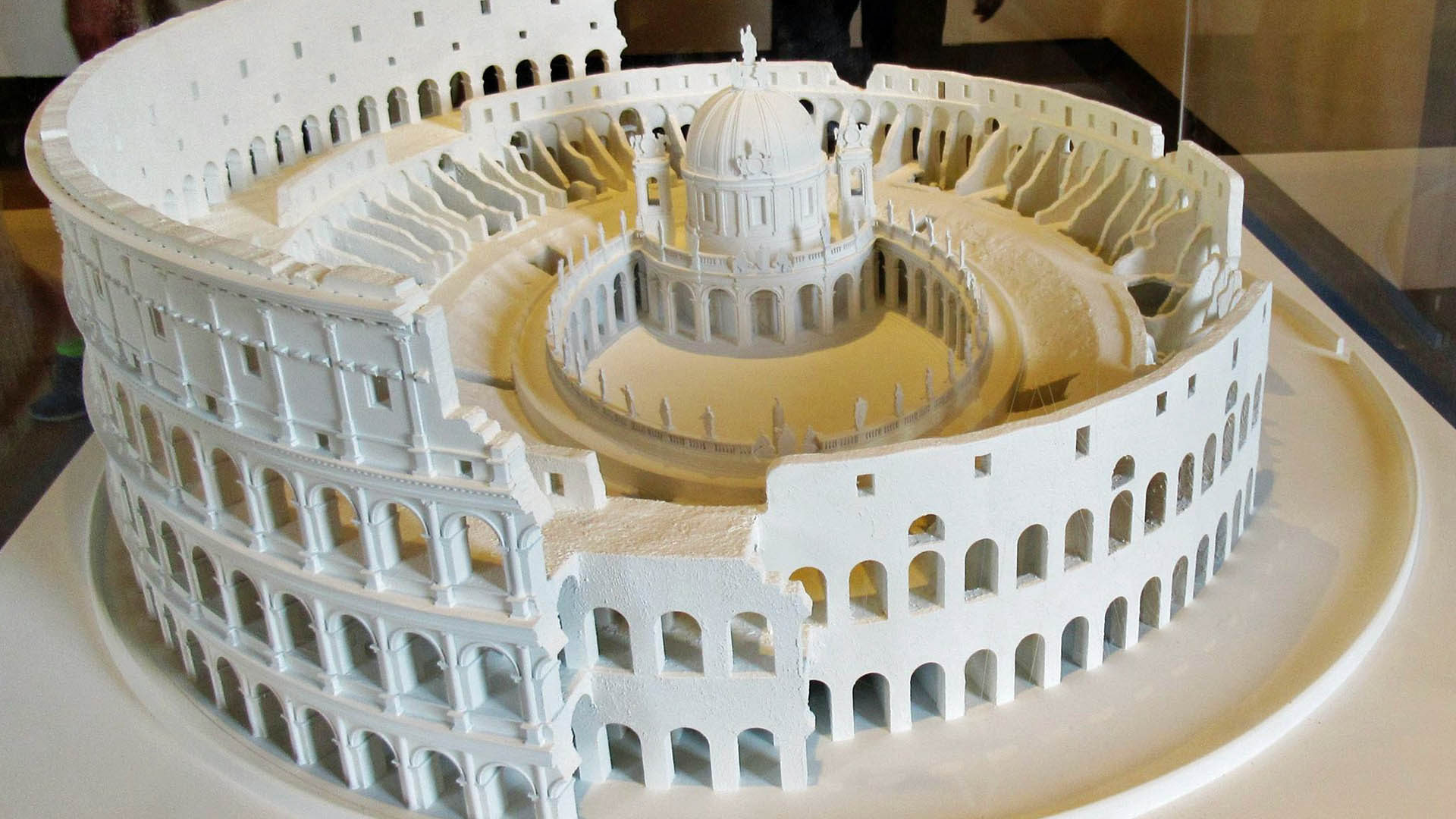

The exhibition in the Colosseum did the same thing, showing not only paintings, but remains from the later development of the site, and scale models of the churches that once existed within the abandoned amphitheatre as well as those that were only proposed. Clearly, there was more to the Colosseum than I had allowed myself to realise.

But there was more even than that. All of this information has long been known, but it was not the focus of discussion concerning the Colosseum. In the years 2010 and 2011, excavations were renewed in the Colosseum in order to learn more about the post-Roman use of the site. Extensive finds of animal bones and structures dated to the tenth and eleventh centuries AD revealed that in this period the Colosseum became a kind of squatters village. Alongside the churches, people lived their daily lives and worked among the ruins. The amphitheatre became a home.

The Colosseum is huge. It is not difficult to imagine it being used in this way, once the idea is presented to you. But it is so different to the idea that we usually have of the monument that it is difficult to imagine independently. So focused are we ancient historians on its importance in the Roman Imperial period, that we do not always think about how such a monument has stood for centuries in the “Eternal City” of Rome. If we don’t always think about what is known, we will certainly be surprised by what is new.

The end of history?

Cooper ends his thread with a lament for the lost features of the Colosseum – not just its plant life, but the ruins removed to restore the secular nature of the monument. While waiting for my flight in Rome Fiuminino Airport this July, I wrote: “In some ways, this makes me wish it had never been excavated.”

Excavation is a destructive process. We must record what we can before we move on – but research programs, often focused on specific periods of occupation, do not always allow for this process. We archaeologists, as well as the public, are focused on the most prominent phase of a monument’s existence. We can see this in the gift shop, where the Colosseum is represented in two stages: complete or in its present, ruined state.

The Colosseum was an amphitheatre, then a ruin, a squatters village, several churches, a biosphere, and finally a monument.

Is this the end of the process? The Colosseum has evolved as a monument over the decade between when I first visited and this summer, when I returned. A monument, a site, a thing is also changing even as we attempt to preserve what it once was.

Monuments will always need to appeal to their most famous moments to bring in non-specialist audiences – as the Colosseum did for me. But I will always find most fascinating that period in which the Colosseum was a village, not an amphitheatre; the smaller history within those colossal arches.