In the previous article in this series, I offered a general introduction to network analysis, giving an idea of how it can be used in archaeology. In this article, we will delve deeper into practical considerations. I will focus on the first step in the process: creating the database.

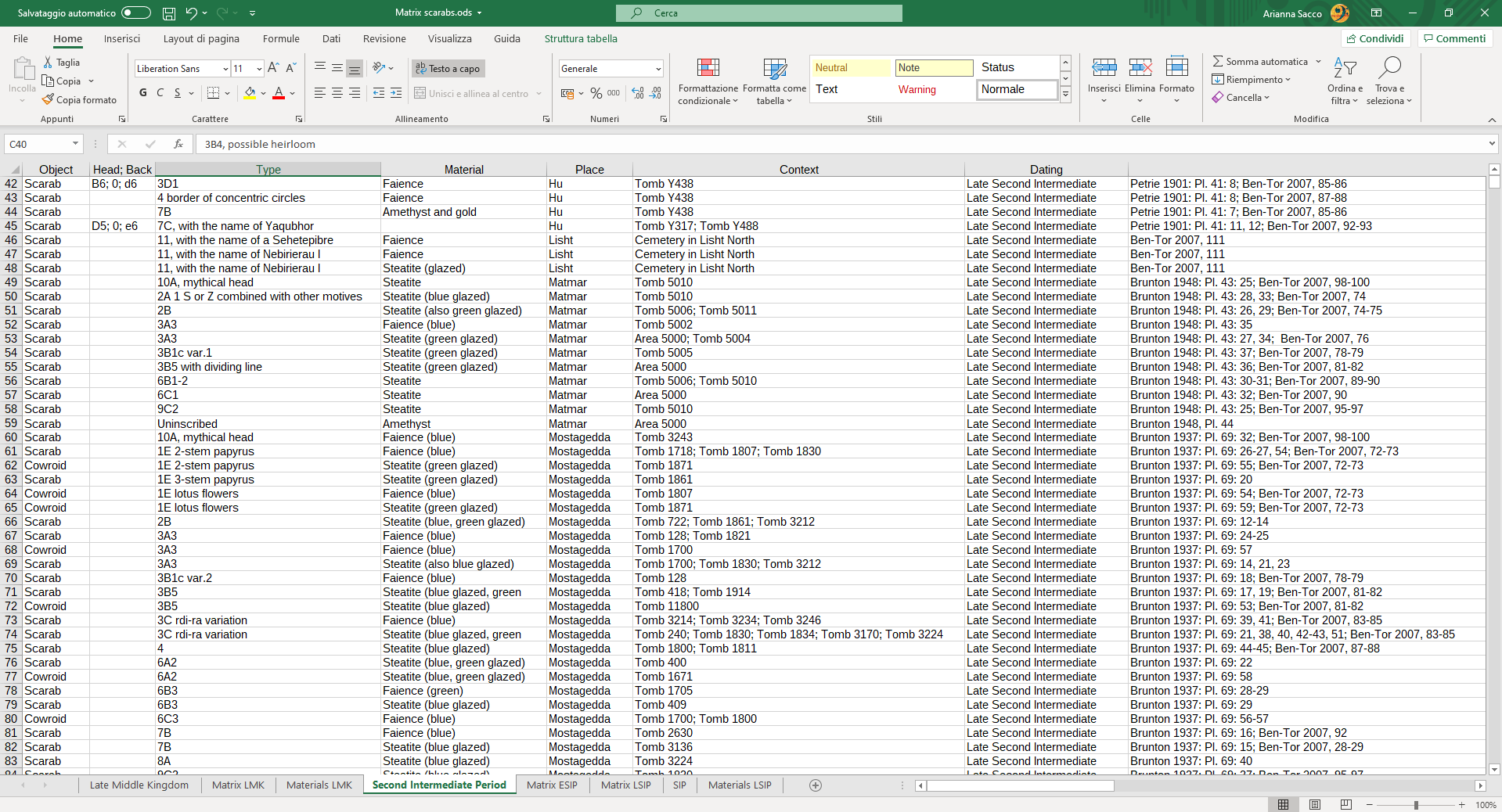

What to put in the database depends, of course, on what you are researching and on your research question(s). For example, with my research, I studied how sites in Egypt were connected and interacted during a period of political and cultural division, based on the objects shared between these sites. I examined the types of beads, stone vessels, seal impressions (the design that is on the base of scarabs and seals), and metal weapons, as well as two types of pottery originally imported into Egypt and later imitated locally (the so-called Tell el-Yahudiyah ware and the Cypriot pottery).

Why did I choose this approach? First, the objects are used by various segments of society and are indicative of different types of activities. They are also found in different types of archaeological contexts: settlements (dwellings) and cemeteries (tombs). Therefore, they give information about different types of sites, or – in those cases where a site features both a settlement and a cemetery – about different areas of the same site. Consequently, the chosen objects provided information on a wide section of the communities in question.

Beads and stone vessels were used by people of both upper and middle class. These objects are found mostly as grave goods, but specimens survive also from settlements. Scarabs and seals were used mostly in administrative tasks, concerning the exchange and circulation of goods and the relevant documentation.

Tell el-Yahudiyah ware and Cypriot pottery were initially imported from Palestine and from Cyprus, and later were made locally in Egypt, i.e. imitated. Therefore, this pottery gives information not only on relationships between Egypt and these other regions, but also about the (changing) tastes and preferences of Egyptian society.

Weapons, which have been retrieved nearly exclusively in funerary contexts, are informative of funerary traditions. They may also show the presence of traditions different from the Egyptian ones, for example when they imitate weapons found in the Levant.

Secondly, there is a very practical reason for why I picked these specific objects: these were the ones for which I was able to find more information (based on previous research), and the amount of data available could be digested within the span of time allocated to my PhD research. Other objects, such as pottery other than the Tell el-Yahudiya and Cypriot vessels, could be incorporated, but that will have to wait for a future postdoctoral research project.

Features

After deciding what material to collect, I need to decide which features I wanted to take into consideration for each object. And since my focus is on finding similarities between regions, I needed to make clear what I would define as similarity. As an example, if I find a faience bead of a similar shape at two sites, is this enough to say that they share a similar type? Do I also need to take the size of the beads into consideration? Do I need to take the colour of the faience into account as well?

Going back to the previous example, if one site has a hippo-shaped bead of blue faience, and another site has a hippo-shaped bead of yellow faience, can I say that they share a similar type? Ultimately, I decided to take into account the shape and the material of the objects, but not to take into consideration the measures and the colour of the objects, nor the techniques used to make the objects; for the seal impressions, I took into account the type of design used.

Why did I decide that? A first reason is that the colour is not informative of real differences. To go back to the previous example, the colour of the faience can change with time, thus the colour seen on the beads is not always the original one.

Another reason is that measurements can also change or cannot be immediately known. For example, a weapon can break, or a blade can become smaller because it has been sharpened time and again (which can also change the shape slightly). And finally, techniques, as well as the measures, are often not reported in the extant secondary literature.

Once I decided that I wanted to focus on the shape and the material of the objects, I had to decide how I wanted to define the shapes. That depended very much on the objects themselves. I did not considered objects that were too fragmentary to reconstruct.

For example, for the seal impressions, I considered the main feature of the design (e.g. floral, with spirals, with a frame). For the stone vessels I considered the shape of the rim and the neck, of the main body, and of the base: I regarded the vessels as similar only when they shared all of these features. Some objects these criteria were simpler: weapons I considered similar when they were of the same type (e.g. axes, swords, spear and javelin points, knives), shape, and material.

Quantitative aspects

Another important decision that I had to make concerned the quantitative aspect of my analysis. Did I want to consider how many objects were found in each context (technically called “abundance”). For example, would it be useful to know how many stone vessels of a specific type were found in a single tomb?

Alternatively, did I want to consider in how many contexts – e.g. how many tombs – the objects were found at each site? Or, instead, did I want to take into consideration only if a type was present at a site or not (a simple binary choice), without counting either the abundance or the number of contexts?

I ended up choosing the third option, because of the data that I had to work with. The publications available did not mention consistently the abundance nor the exact number of contexts. Therefore, taking that into consideration would have skewed my analysis, giving more importance to the sites for which the abundance and the contexts are reported.

Moreover, the finds and the contexts known in the archaeological record do not represent all that was once present at a site. To go back to the example of the beads, it can happen that during the excavations some of them are overlooked. A few are also small enough to pass through sieves. Hence, the number of beads that are reported almost certainly are incomplete.

Another example is perhaps also illustrative. When excavating, it does not necessarily follow that what is unearthed is complete. The tombs that may have been dug up do not necessarily reflect the total number of graves that are actually present at the site. Therefore, counting the contexts would have again skewed my analysis, making the sites where more has been discovered – or where excavations were more intensive – appear more important than they actually may have been.

Periodization

The next step was deciding how to internally divide the period under investigation. The period is dated in absolute terms from ca. 1850 to 1550 BC. It includes the later part of the Middle Kingdom (up to ca. 1775 BC), when there were precursors to the phenomena visible in the Second Intermediate Period, and the Second Intermediate Period itself (ca. 1775-1550 BC).

The separation between the Late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period is self-explanatory. However, the Second Intermediate Period also needs to be separated into an early part (pre-Hyksos rule) and a late part (contemporary with the Hyksos), because these two parts are characterized by different politics and by different relations between the various regions in Egypt.

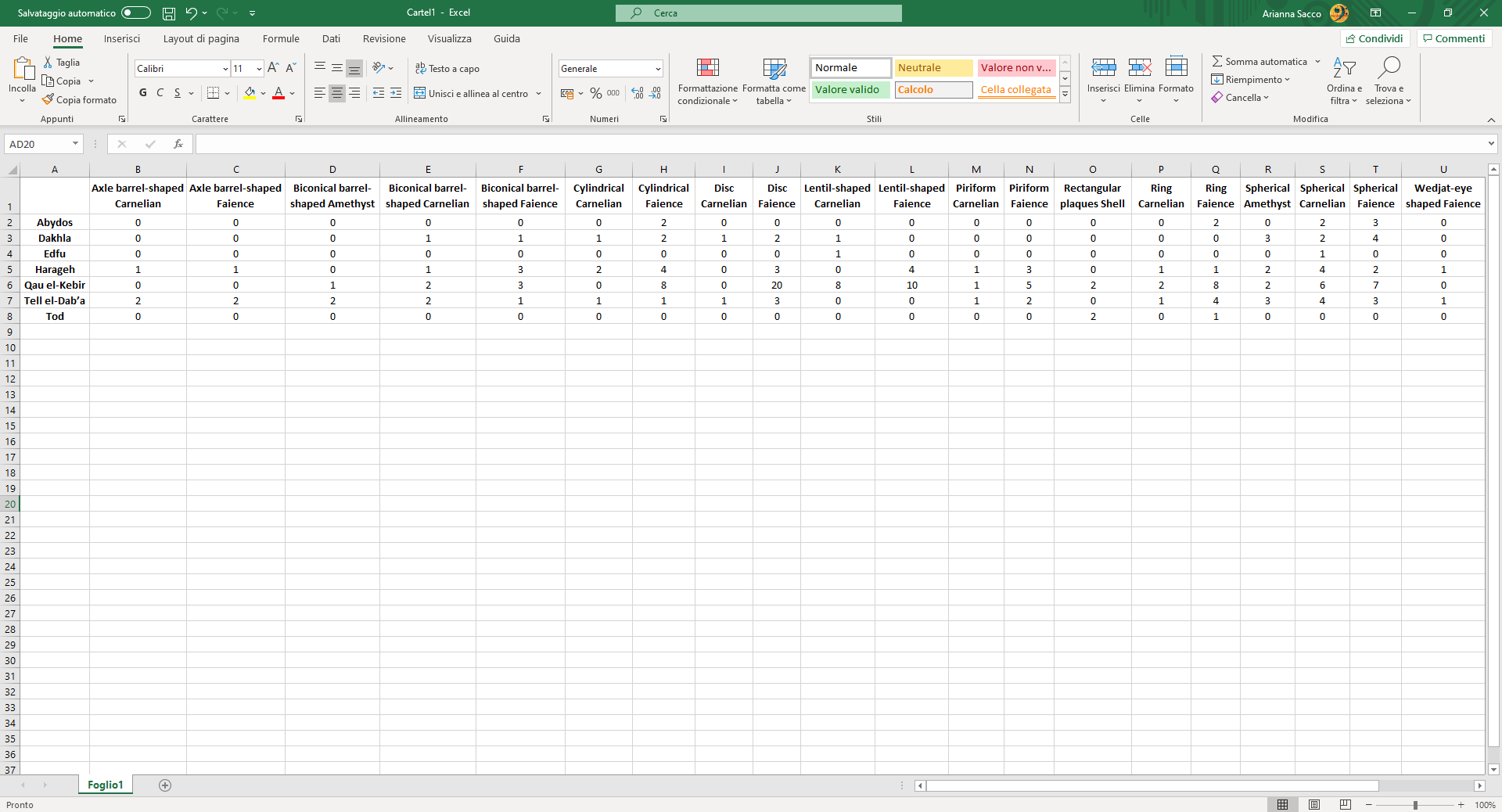

After dividing the sites into the three main periods mentioned, I counted how many types of objects – that is to say objects of a similar shape and material – the sites of each period share with each other. This led to the creation of matrices, where the sites and the amount of types shared are reported: each row corresponds to a site, and each column corresponds to a type of object.

There is also another, more complex, type of analysis that I carried out, which considered the entire range of objects, not only the shared types. But this will be a subject for a future article.

Conclusions

To conclude, you can see that there are many factors that I had to think about when I started my study, and many choices to make that had profound consequences for my analysis and my results. I made my choices based on the data available – which I was collecting from publications – and by evaluating which data would actually be significant with regards to determining differences and similarities between sites. All these decisions were made to facilitate answering my main question.

With a different set of data, my choices would probably have been different. For example, if I had more data about the dimensions of the objects – and if that information were useful to my research – I would have included those too as part of the criteria for what constitutes a similar type. In that case, objects found in two sites would have been considered similar if their shape, material and their size were similar.

Before I leave you, I would like to say one more thing: though I didn’t include some of the data into the analysis, I put it into my database anyway. So, for example, when the information was available, I recorded in which contexts the objects were found, and what colour the objects were, or the type of scarabs to which some of the seal impressions belonged.

Writing the data down is useful for the sake of completeness. It will serve as a basis when in the future we will be able to include more data. Moreover, it gives a larger picture, which helps in interpreting the results of network analysis. Future researchers may also find it useful when the database is eventually released in Open Access.

The next article in this series will be about what happens when the matrix is imported in the software used for network analysis.