Archaeologists are often forced to work with scraps. Nowhere is this more clear than when it comes to frescoes of the Bronze Age. At the so-called “Palace of Nestor” in Pylos, a Mycenaean palatial centre in southwest Peloponnese, large numbers of fragments of frescoes have been recovered.

Among these fragments are a collection that have been reconstructed by Piet de Jong (1887-1967), an English illustrator of Dutch descent who worked on a number of Aegean sites. Among other things, he reconstructed the Dolphin Fresco at Knossos, as well as that centre’s throne room, and made an illustration of what the throne room (megaron) of Pylos might have looked like. (On Twitter, Prof. Louise Hitchcock pointed out to me that Piet de Jong created his famous reconstruction of the Pylos throne room before the frescoes had been cleaned.)

The fragments from Pylos include a small piece, about 15 cm in height and 10.5 cm broad, which forms the subject of the present article. It dates to Late Helladic IIIB (roughly, the thirteenth century BC). It was found in Room 43, “high in fill”, according to Mabel Lang’s description, who also adds that it was found in “Poor condition” (p. 69). The fragment depicts the neck and face of an apparently male figure, as well as part of his shoulder and arm. He wears a light tunic; a curving band next to his arm is rendered in a dark colour.

A figure with a shield?

Based on this fragment, Piet de Jong painted a watercolour painting in which the figure has been restored, based on the evidence from other, better preserved fresco fragments. De Jong believed that the figure was equipped as a hunter, and thus gave him a spear in his raised, left (!) hand. His legs are equipped with the typical gaiters familiar from other depictions of both warriors and hunters.

De Jong interpreted the curved, dark band behind the figure’s right arm and shoulder as part of a shield. And not just any type of shield, but one equipped with a central armband and a grip near the edge of the rim. In other words, if Piet de Jong’s reconstruction is to be believed, we are dealing here with a type of shield that wouldn’t be seen again in the Aegean until the late eighth century BC, the so-called Argive shield with double-grip.

In her catalogue, Lang is cautious about whether or not this fresco has been correctly reconstructed. She adds a question mark in parenthesis after the word “shield”, and in the description she writes that the “wide black arc which the arm appears to cross may be the upper part of a shield, held by an arm strap so that it is inside out” (p. 69, my emphasis).

Given enough time, however, images like this can start to lead a life of their own. In his 2005-book on Mycenaean warfare, Nicolas Grguric includes De Jong’s reconstruction and notes in the caption that it depicts (p. 17):

a later period warrior with a round shield. Since the exact position and length of his weapon can only be guessed at, it is difficult to know whether he is a javelinman or a spearman, although the presence of a shield makes the latter more likely.

For Grguric, the shield is not in question; instead, he worries about the length of the figure’s spear! At this point, it’s useful to again look at the original fragment and realize that the spear itself has been added by Piet de Jong on the assumption that this figure is a hunter or a warrior. (In general, spears held overhead like this in Late Helladic IIIB art tend to be short, i.e. javelins.)

Diane Fortenberry also discusses this fragment in her PhD thesis, although she accidentally assigns the find to room 48 instead of 43. She emphasizes the context of the find: “other pieces in better condition […] have been reconstructed to form a scene of hunters in procession” (p. 25). She also emphasizes that the presence of a round shield is rare, if not unknown: she points to a Late Helladic IIIC (i.e. twelfth century BC) krater from Tiryns as a possible parallel.

However, Fortenberry rightfully doubts that the figure is a warrior, as some have suggested, as “battles on the Pylos frescoes are always fought by bare-chested Mycenaeans” (p. 26). She also emphasizes that the arm strap cannot be a central armband because shields of that type are unknown before the Archaic period (ca. 800 to 500 BC).

I would go so far as to say that the fragment in question preserves little evidence for any kind of strap or armband at all. If you look carefully at the photo of the actual fragment, there doesn’t seem to be a strap. The strap from the water colour seems to be located just outside of the area of the original fragment, and it seems to have been put there simply to corroborate the idea that the dark band is part of a shield.

And speaking about this dark band, Piet de Jong painted this in his reconstruction as if it were part of a perfect circle. But the photo suggests the curve isn’t nearly as perfect as the watercolour suggests. Instead, it appears to be a bit oblong. Could it be the top part of a figure-eight shield? This, too, seems unlikely, since those body-shields would cover most of the body and would not be suspended casually from an extended arm, let alone a right arm, too.

Most likely, the reconstruction is incorrect, and can certainly not be taken as proof for the use of round shields with a double-grip construction during the thirteenth century BC. Undulating lines, though usually not as broad as indicated on this fragment, occur frequently in frescoes from Pylos. They are often regarded as representing geographic features, perhaps even rivers in some instances, although a purely decorative function cannot be dismissed either. Most likely, the dark band is part of just such a feature.

Shields in the later Mycenaean era

Shields are rarely depicted in art after the era of the “Shaft Graves”, as I pointed out in my article on the Dendra panoply. If the fragment from Pylos really depicts a shield, it is unique and prefigures shields that would reappear in the Aegean only centuries later.

Not only are its shape and the arrangement of its grip unique, but the context doesn’t fit either: building on what Fortenberry wrote, there are no other frescoes of the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BC that depict hunters equipped with shields.

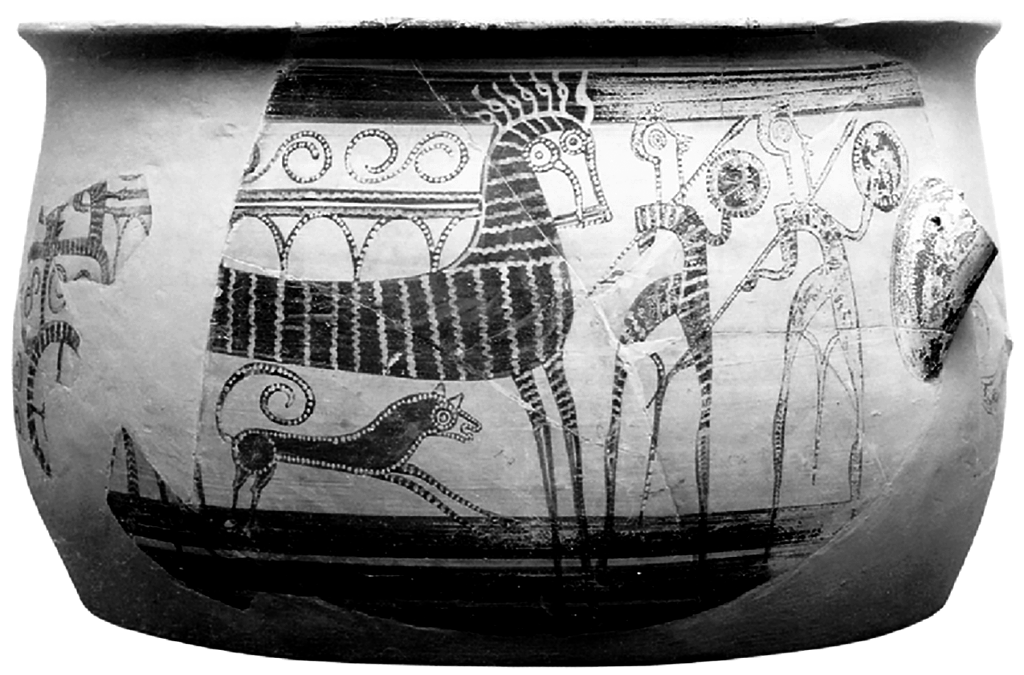

This is not to say that round shields did not eventually (re)appear in the Aegean. A fragmentary krater from Tiryns depicts a chariot and two warriors with spears. They also each carry a small round shield. Unlike is the case in Piet de Jong’s reconstruction of 18 H 43, these shields are held further away from the body, with the hands grasping a central handle that isn’t visible.

The scene on the krater doesn’t allow us to say much in detail. The shields appear to be fairly small, more like bucklers than anything else, but it is usually a bad idea to assume that an artist intended to represent real life accurately – after all, a painting is not a photograph. The krater has been dated to either the very end of the thirteenth century BC or a little later. The latter is more likely, but even if it does date to Late Helladic IIIB, it should only serve to make us more suspicious about the Piet de Jong’s reconstruction.

The moral of this closer investigation of a particular fresco fragment is that you shouldn’t rely blindly on reconstructions, but always check the original material. As I stated in my article on the Dendra panoply, warfare in the Late Bronze Age is a fascinating subject, but also one where you have to be extra careful not to jump to conclusions.

Further reading

- Diane Fortenberry, Elements of Mycenaean Warfare (unpublished PhD thesis; University of Cincinnati, 1990).

- Nicolas Grguric, The Mycenaeans c. 1650-1100 BC (2005).

- Mabel L. Lang, The Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Western Messenia. Volume II, The Frescoes (1969).