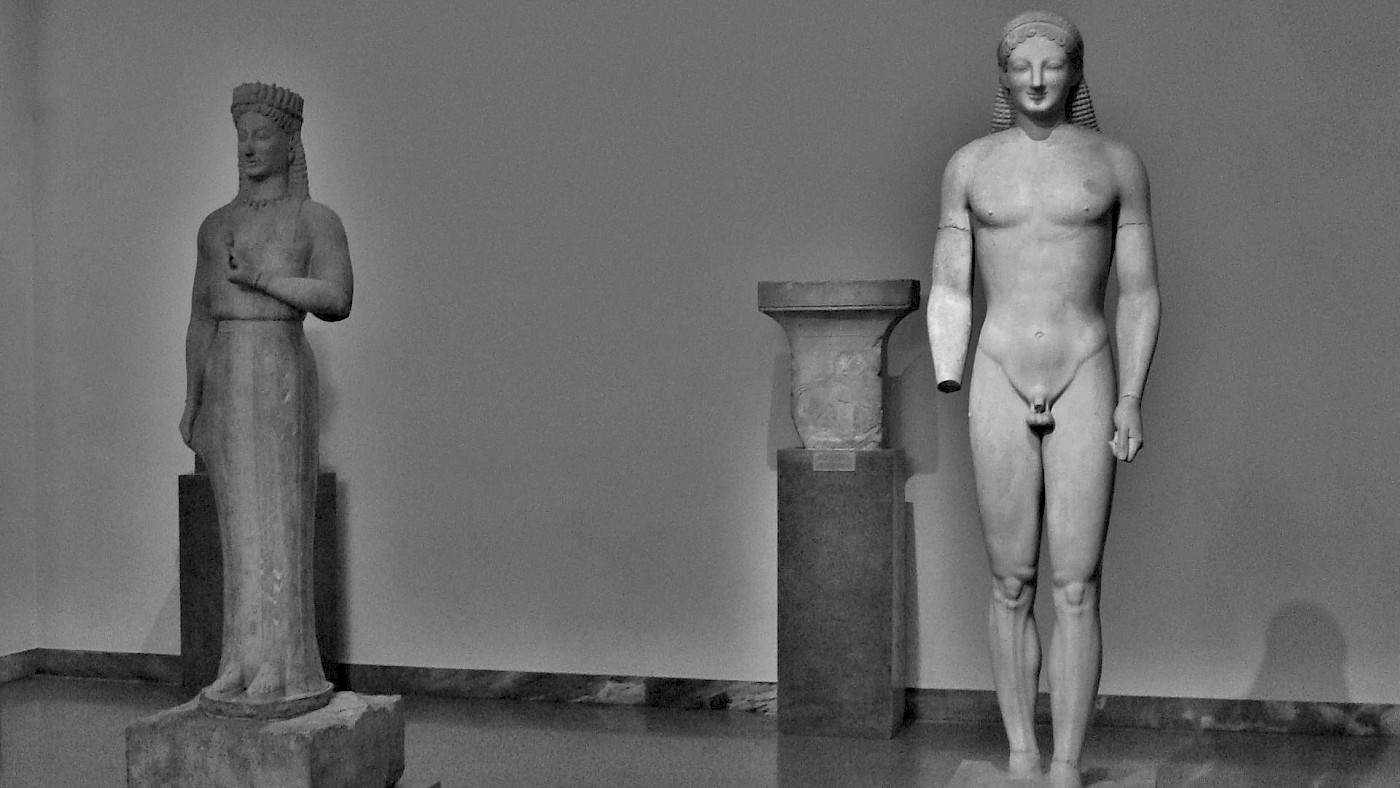

In the summer of 1972, an excavation in Merenda, ancient Myrrhinous, in Attica, revealed two statues that had been buried together in a pit during the Archaic period. One statue is of a male youth, the kind we call a kouros (pl. kouroi), from the ancient Greek for boy; he stands with his hands by his side and his left foot forward in a striding motion. The other is a young woman in a long gown, her right hand by her side grasping her dress, her left before her holding a flower – which we call a korē (pl. korai), from the ancient Greek for girl.

Kouroi and korai are among the first large-scale, free-standing stone sculptures known in Greece in the historical period. They first appear around 640 BCE, inspired by the long-standing tradition of similar statues in Egypt – but distinctly Greek in the nakedness of the kouroi. They were dedicated as votives to the gods in sanctuaries across Greece, including large-scale cult statues such as the Naxian colossus representing Apollo from his sanctuary on Delos; they also marked the graves of those who died young, if their survivors were wealthy individuals who could afford the lavish expenditure of a monumental grave marker.

The find context of the pair from Merenda is unusual. Their state of preservation, including evidence of polychromy on the korē’s dress and kouros’ hair, indicates that they were buried together intentionally not long after they were originally created in the mid-sixth century, ca. 550 BCE. Speculation regarding what prompted their burial varies. Around the same time as their creation in 546 BCE the Athenian tyrant Peisistratus returned from exile, and so it may be that his political opponents felt they needed to protect the monuments to their dead. If their burial was some time later, it may have been to protect them from the Persian sack of Athens in 480 BCE.

Even more remarkable is that the korē is associated with a base, reused as part of the structure of a nearby church and known since 1729 CE. The inscription on the base names the girl, Phrasikleia, as well as the korē’s sculptor, Aristion of Paros. As such, even though their find context was not their display context, we can be sure that these statues were grave markers.

The association of the Phrasikleia korē with a name and inscription means that she has been a central part of our understanding of funerary monuments of the sixth century BCE since her discovery nearly fifty years ago. Meanwhile, the deceased marked by the boy remains nameless, one of a number of nameless kouroi that marked the graves of young men in sixth century Attica.

Phrasikleia and the boy

The korē of Phrasikleia stands ramrod straight, her feet side by side. Her right arm is extended by her side and pulls at her chiton, her left is bent in front of her chest holding a closed lotus blossom. Lotus blossoms also form the crown which sits atop her braided hair. She stands 1.76 metres tall, probably a little over life-size.

Phrasikleia is dressed as a bride, yet her inscription tells us that she never married:

Monument to Phrasikleia

Korē I shall forever be called

This name

Given to me by the gods

Instead of marriage

As such, Phrasikleia is forever a korē, an unmarried girl. She is memorialized in the ideal form of a young woman: youthful, poised, elegant, and ready for the marriage she never had.

Korē, however, is also one of the names given to Persephone, the daughter of Demeter who was abducted by her uncle Hades to be his bride in the underworld. Scholars, including Judith Barringer, have suggested that this reference in Phrasikleia’s epitaph could refer to this myth – when an unmarried young girl died, she metaphorically became the bride of Hades.

The kouros with which Phrasikleia was buried has no inscription, and thus takes up far less space in our histories of ancient Greek art. He is often only referenced for his relationship to her, found in the same pit, but we do not know any more about their connection. Perhaps they belonged to the same family, siblings or cousins, or they were betrothed and died together in a tragic accident. We will never know. As such, he is one of dozens of similar statues of naked young men known from sixth-century Attica and beyond: just a boy.

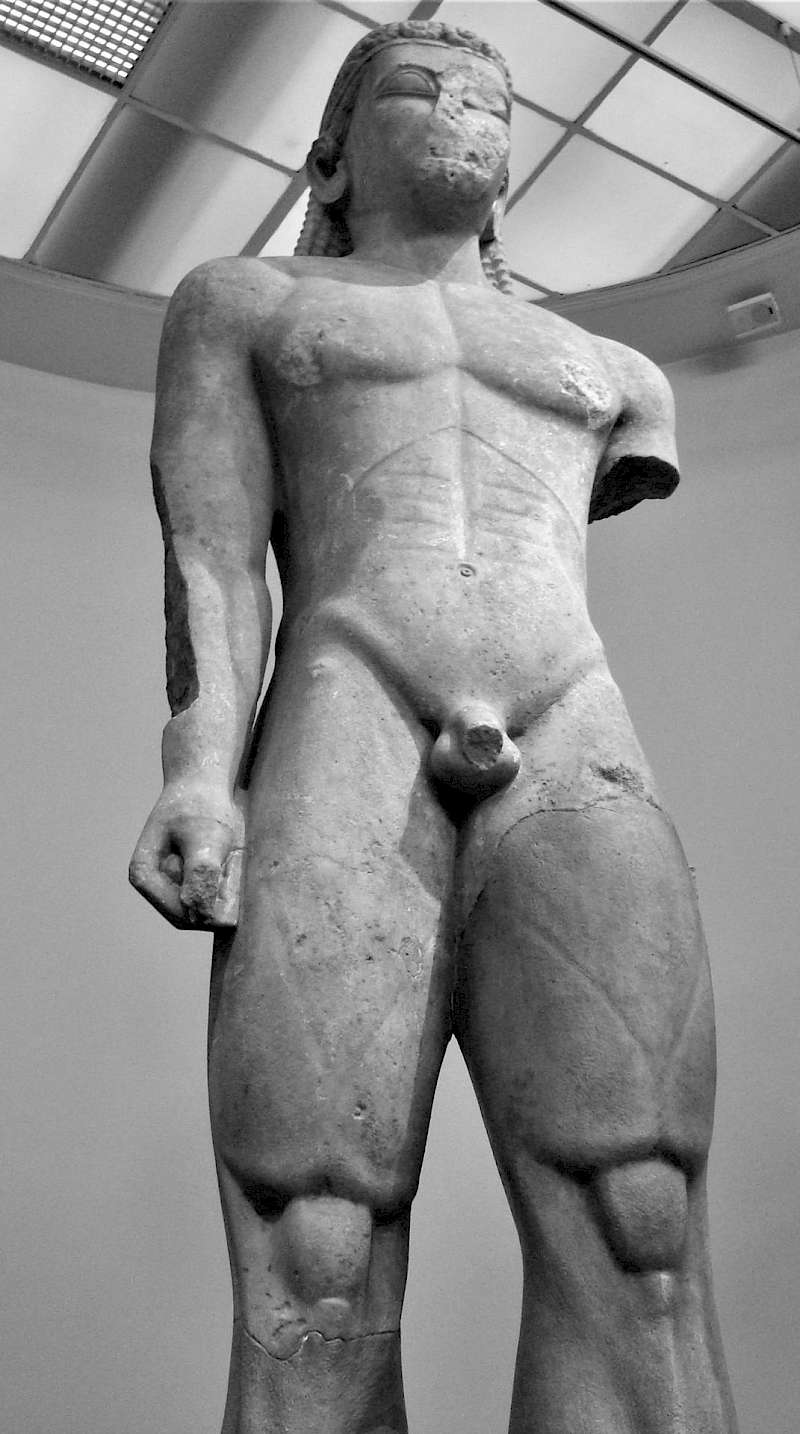

The boy is nearly entirely preserved, missing only his right hand, his feet, and much of his penis. Aside from the fillet around his head, around which his painted-red hair curls, he is entirely naked. He has the familiar almond-shaped eyes, braided hair, and Archaic smile of many kouroi, above a smooth chest and rounded limbs. Around his nipples are small holes to indicate areolae, where red paint survives; on his torso, tight abdominal muscles and a deep inguinal line indicate body tone.

His stance conveys movement – his left leg extends slightly forward, his right back, while his arms bend slightly at his sides. The surviving left hand is closed, not tightly, but the position of the thumb indicates that he was not originally holding anything. He is taller than Phrasikleia – 1.89 metres preserved – and so was originally slightly larger-than-life.

While this kouros is a fine example of the type, it must be said that there is almost nothing remarkable about the boy among the whole corpus of known kouroi.

Boys and girls

When we talk about Phrasikleia and the boy, we are not really talking about Phrasikleia, the girl commemorated in this statue, or the unknown young man whose grave was marked by this kouros. We do not know the burial they marked; we do not know their age, their life experience, or indeed anything much about them.

What we have is an example of the ideology and expectations of wealthy Attic people in the mid-sixth century when it comes to the roles of boys and girls. It seems clear, from this surviving evidence, that these elites viewed gender as a binary, and had strong patriarchal ideas about what was expected of their children. Indeed, looking at Phrasikleia and the boy next to one another, as they are displayed in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, offers a striking contrast between the two genders recognized by those elites.

The boy is not especially remarkable as a kouros, but this in itself is useful information. Kouroi represented an ideal of youthful masculinity on full display: One of the innovations in Greek statuary when adopted from Egypt is that these young men are naked, showing off their entire physical form.

Despite the strong association between Greek culture and male nudity emphasized from at least the fifth century BCE (Herodotos 1.10.3; Thucydides 1.6), it is not that common for men to be depicted completely naked in the seventh and sixth centuries. Bearded adult men wear armour on their grave stele, and black-figure vase painters also preferred to show people clothed. In the poetry of Tyrtaeus, nakedness is associated with the vulnerability of an old man who dies clutching his bloodied genitals, and with light-armed warriors, called gymnetes (sing. gymnes), literally meaning “naked men”.

And yet there are dozens of naked kouroi known from the cemeteries and sanctuaries of Archaic Greece. This nudity is likely connected to their youth – kouroi do not have beards, and most do not have pubic hair, although on those that do it is very stylized; when young men appear on grave stelai, they are also naked and beardless. Although calling these statues “boys” is a modern convention, their use as grave markers does appear to have been for the burials of young men. The graves of older men seem to have usually been marked by stelai, or very rarely ceramic plaques.

Similarly, when korai are used as grave markers they appear to be for young, unmarried girls like Phrasikleia. In contrast, these are never naked. Phrasikleia wears a chiton, a cylinder of fabric pinned at two points along the top to create holes for the head and shoulders; other korai may also wear a himation (“mantle”) and even a shawl over this dress. The later sixth- and early fifth-century korai from the Acropolis in Athens often have much more elaborately carved drapery, with deep folds implying a human body beneath.

Phrasikleia’s clothing implies nothing about the shape of the human body imagined beneath it. This may be a cultural standard of modesty imposed on girls and not boys; however, the sculptor Aristion also did not show the effect of her hand, pulling on the chiton, on the lower hem, implying he was either uninterested or incapable of showing realistic movement of fabric.

The contrast between these two statues helps us to see the differences between the ideological expectations imposed on Attic boys and girls in the sixth century: boys are shown in movement, with muscular bodies on full display; girls stand straight, still, awaiting the fulfilment of marriage. So far, so patriarchal.

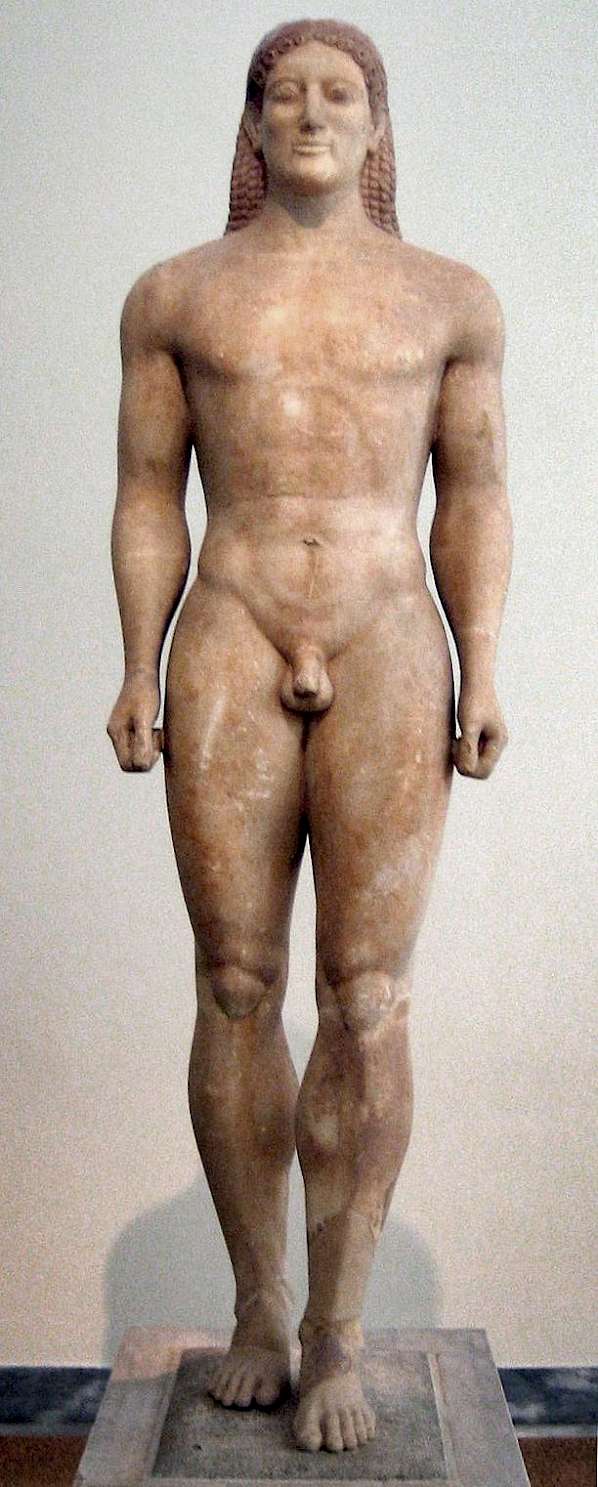

We can expand on this contrast further by comparing Phrasikleia’s inscription to that of a young man dated a decade or two later. A kouros from Anavysos, dated ca. 530 BCE, has been connected to a base inscribed:

Stand and mourn Kroisos

He is dead, this monument is his.

Fighting in the front rank

He was destroyed by Ares.

The Kroisos kouros is slightly taller than the boy at 1.94 metres, and there is perhaps more detail to his musculature; their pose, however, is identical: left foot forward, hands at their sides, looking straight ahead, naked. We could also assume that the youth whose grave was marked by the boy was similarly killed in battle, but we do not know. Kroisos is represented beardless and naked, an ideal youth rather than an adult like the armoured warriors with beards we see on contemporary stele.

There are numerous differences between Kroisos and Phrasikleia’s inscriptions. Phrasikleia’s inscription is in the first person, a statement of who she was: an unmarried girl. Meanwhile Kroisos is referred to in the third person, and the inscription makes demands of the viewer through imperatives: stand and mourn. According to this inscription – which we need not necessarily believe – Kroisos was not struggling to attain an ideal, he achieved it: he fought in the front line in battle and was destroyed by the war-god Ares. For his achievements, he demands respect; Phrasikleia, unmarried, failed to fulfil her potential.

And yet, the cost of Kroisos’ achievements was great: his death. Patriarchal Athens celebrated its young men, offering them glory and honour through battle, but those with the greatest monuments in Attic cemeteries may have been destroyed through their fulfillment of this ideal.

What if Phrasikleia had fulfilled the potential sixth-century Attic society ascribed to her, and married? There are no older women represented by free-standing sculpture of the sixth century, nor are they well known on grave stelai – in contrast to their dominance in that medium from the late fifth century. In the mid-sixth century, they are represented as the deceased primarily on small ceramic funerary plaques, large in number but small in size. In the cemeteries of Archaic Attica, the young – especially young men – dominated the landscape.

Concluding thoughts

Phrasikleia and the boy are a fine example of beautiful Attic free-standing sculptures of the sixth-century BCE. They also reveal much about the patriarchal gender standards of elite Athenians of the Archaic period. Phrasikleia is entirely defined by the fact that she was unmarried when she died; she stands, passive, eternally awaiting marriage. Meanwhile the boy is active and athletic, his body on full display. Inscriptions connected to other kouroi suggest that his achievements may have been celebrated in an inscription; although these achievements may also have killed him.

Despite their relatively low numbers, these monumental young figures would have dominated the landscape in an Attic cemetery of the Archaic period. Older men with battle or athletic achievements were represented by stelai, which while impressive would not have stood so prominently, while women who married were represented by tiny ceramic plaques. Cemeteries were dominated by the gendered potential of youth – fulfilled or otherwise.

Further reading

- Judith M. Barringer, The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Greece (2014).

- Matthew Lloyd, “Making Men and Making Women: ‘Male superiority’ in archaic Athens,” in: Tatiana Tsakiropoulou-Summers and Karerina Kitsi-Mitakou (eds), Women and the Ideology of Political Exclusion (2019), pp. 57-73.

- Robin Osborne, “Looking On – Greek Style. Does the sculpted girl speak to women too?” in: Ian Morris (ed.) Classical Greece: Ancient Histories and Modern Archaeologies (1994), pp. 81-96.

- Mark D. Stansbury-O’Donnell, A History of Greek Art (2015).