The Graeco-Roman god of the vine, Dionysus, is usually shown accompanied by an extensive retinue that includes a variety of lesser divine beings. These include the Maenads, who are drunk or raging nymphs, who, for example, tore the unfortunate singer Orpheus to pieces when he refused to move out of their way.

Aside from the Maenads, the followers of Dionysus also include a number of other creature who in art are shown as a mixture of human and animal characteristics. They include satyrs, sileni, and fauns. They are essentially nature spirits. Whereas nymphs are female, the satyrs, sileni, and fauns are all male. The difference between these three distinct entities isn’t always clear, but they are not that hard to tell apart once you know what to look for.

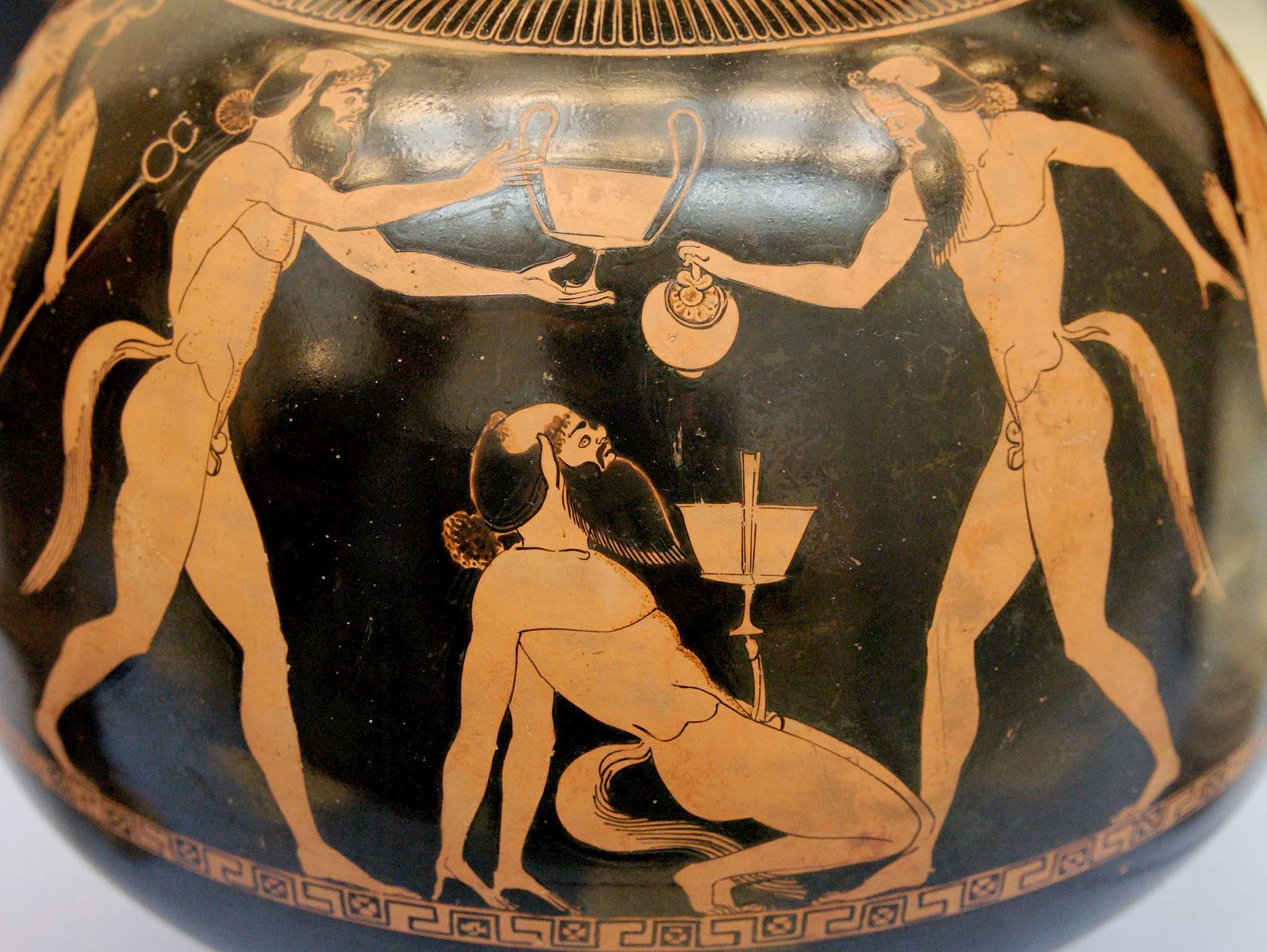

Satyrs have the tail, ears and, rarely, the legs of a horse. In ancient Greek theatre, satyr plays featured choruses of satyrs. Satyr plays were short and inspired by Greek mythology. They were tragicomedic and featured crude humour, with plenty of sexual references. A famous satyr was Marsyas, who lost a musical contest against the god Apollo and was flayed for his arrogance.

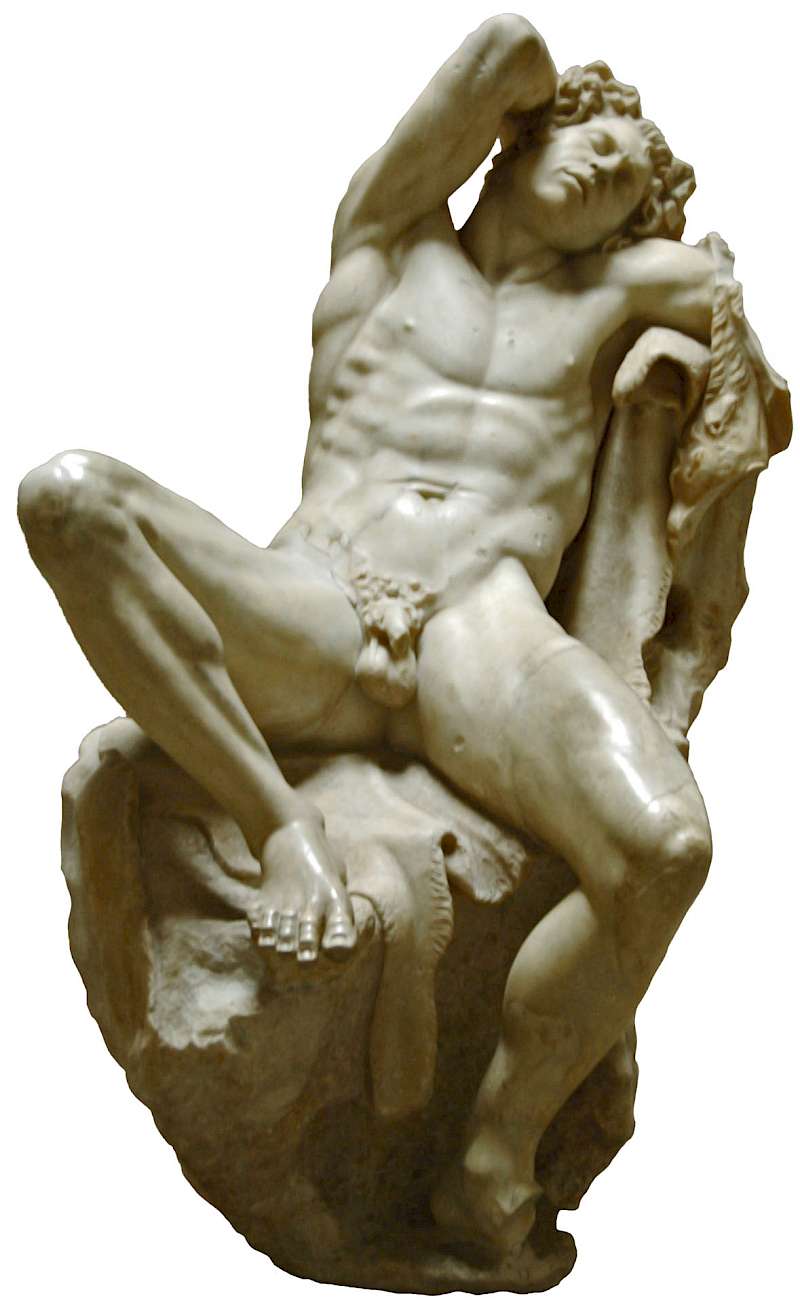

The sileni are essentially older satyrs. In art, they are usually depicted with bald or balding heads; sometimes, their beards and hair are coloured white. The most prominent of their number was Silenus, who played an important role in the satyr play The Cyclops by Euripides. Silenus is sometimes depicted as much older and more out of shape than normal; in this guise, he’s sometimes referred to as Papposilenus.

Finally, we have the panes or fauns, who are named after the ancient Greek god Pan. Pan represented untamed nature; his key attribute was the pan flute. The Romans referred to Pan as Faunus. Like satyrs and sileni, the panes or fauns were mostly human in appearance, but unlike the former were depicted with the legs and tail of goats. Sometimes they are also depicted with the head of a goat.

Satyrs, sileni and fauns are often depicted as lustful creatures, not infrequently drunk. Satyrs in particular are nearly always depicted with (exaggerated) erect phalli; the technical term is “ithyphallic”. As older and presumably wiser creatures, sileni are sometimes depicted with flaccid rather than erect members. Satyrs in particular are often shown trying to seduce or rape nymphs, but they sometimes set their sights on other unfortunate victims, too.

The drunken and rowdy behaviour of satyrs invites comparison with centaurs, creatures who had the body of a horse with the upper torso, arms, and head of a human being in place of the horse’s neck and head. Centaurs couldn’t hold their liquor and, like the nature spirits discussed in this article, were prone to rape and debauchery.