Last month, we spent several weeks in beautiful Southern Italy. During that time, we also managed to revisit Paestum. We first visited Paestum in 2012, but unfortunately I either forgot my camera or my batteries had run out, and was so unable to take any pictures, much to my chagrin. This year, however, I came prepared and took more than 700 pictures in the museum and on the site.

A brief history of Paestum

Paestum is a beautiful site with a great museum. This Italian town is located in the province of Salerno in the region of Campania (with Naples as its capital). The city was founded in ca. 600 BC as Posidonia by Greeks, probably from the city of Sybaris. Sybaris itself is located further south, close to Taras (modern Taranto), and was in turn founded ca. 720 BC by people from Achaea and Troezen, a region and city respectively in the Peloponnese. The inhabitants of Sybaris gained a reputation for hedonism (hence ‘sybaritic’ as a byword for opulent luxury).

Posidonia was located near the coast and named after the ancient Greek god of the sea, Poseidon. Located close to Naples and other Greek foundations such as Cumae, the inhabitants had to compete with the originally Euboean colonists there, as well as with the Etruscans from further north (modern Tuscany), who were also active in these southern regions of Italy.

Posidonia flourished in this fertile region and some of the most impressive archaeological finds date from this period, including the monumental stone temples and the so-called Tomb of the Diver (ca. 475 BC). But at some point in the fifth century BC, probably towards the end, the city was conquered by the native Lucanians, who spoke an Umbrian-Oscan language and who were neighbours of the Samnites. The city was renamed to Paistos and the archaeological finds show a mixture of Greek and Oscan material. Most of the famous tomb paintings date from the fourth century BC and thus belong to the period in which the settlement had been annexed by the Lucanians.

The Graeco-Lucanian inhabitants of Paistos ally themselves with Pyrrhus of Epirus when he arrives in Italy in 281 BC to lend aid to Tarantum (Taras) against the Romans. The Romans nevertheless managed to conquer much of the Italian peninsula by 272 BC. Paistos was refounded as the Roman city of Paestum. In this form, the city managed to grow and flourish until the fourth century AD, after which it slowly declined. It was abandoned by the seventh century.

By the eighteenth century, renewed interest in ancient sites – thanks to the discoveries at Pompeii and elsewhere – led to the rediscovery of Paestum. The modern village has about a thousand inhabitants and seems to rely largely on tourism. Fortunately, the site is never very crowded, perhaps because it is a little out of the way, though the train that runs between Naples and Sapri stops there and the station is only a short walk from the site and the museum.

The archaeological museum

Paestum’s archaeological museum features an extensive and exquisite collection of archaeological objects. The most notable elements of its collection are the painted tomb slabs. Most of these decorated tombs date from the Classical period and are part of a tradition that is otherwise unknown in mainland Greece, where the only elaborate tomb architecture is otherwise found in Macedonia. Other painted tombs are encountered, for example, in Anatolia, belonging to the wealthy inhabitants of Lydia and Lycia in particular.

The tombs from Paestum are therefore best understood as a native Italian product with a lot of Greek influence as far as style is concerned, especially as they remind us of the painted tombs used by the Etruscans further north. Most of the tombs from Paestum have a similar structure, being made of four wall slabs and a closing slab for the lid; some tombs have a gabled roof. The painted scenes themselves are often thought to have been executed in a style similar to what we find on Greek painted vases, except that the artists used a larger variety of colours.

The oldest of the painted tombs is the so-called Tomb of the Diver. The wall slabs feature a symposium scene with men reclining on couches and enjoying food and drink (see the picture, above). The closing lid slab shows a pool and a naked man leaping off a stone column with a board into the water. The scene has often been interpreted as showing the deceased jumping into the afterlife, but it might as well represent him just enjoying a good swim as much as he enjoyed a good drink with friends. The owner of the tomb may well have been a native Italian, rather than a Greek – though that is a difference probably more important to modern scholars than it may have been for the people involved (but that’s a subject for another article).

Most of the decorated tombs date from the fourth century BC. The painted scenes show a variety of different subjects, all of which clearly related to the lifestyles of the aristocracy, with scenes of chariots, horses, fighting, and feasting. These tomb paintings all date from after the Lucanian conquest of Posidonia, yet the subject matter shows that similar interests much have been important to Lucanian elites as much as Greek ones. The grave goods often contain pottery and other material with distinctly native Italian shapes.

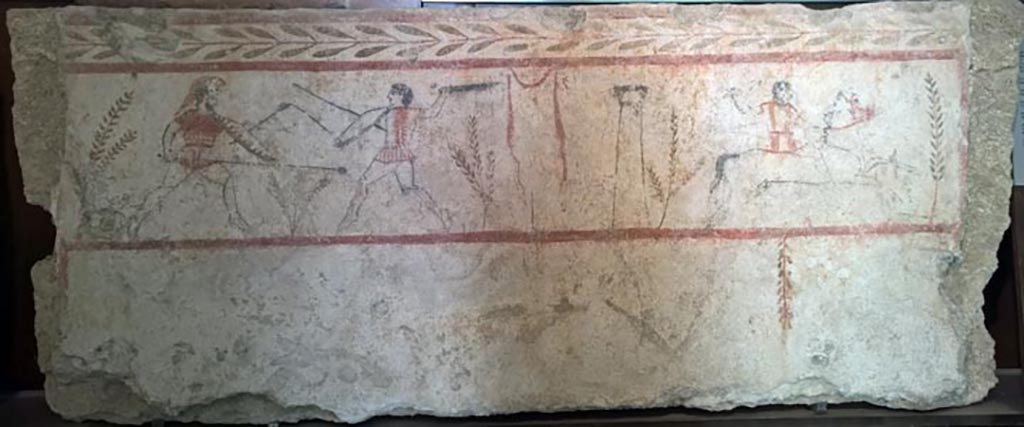

The northern slab from Tomb 271 from Paestum, shown above, dates to the first quarter of the fourth century BC. It depicts a duel (left) and a rider (right). The duel is interesting: it features two warriors that each have a spear lodged in their shield. A picture like this reminds us of the Iliad, where battles between warriors often start by each of them throwing a spear and hitting their opponent’s shield, before closing in and continuing the fight. It may well have been inspired by epic descriptions of battle.

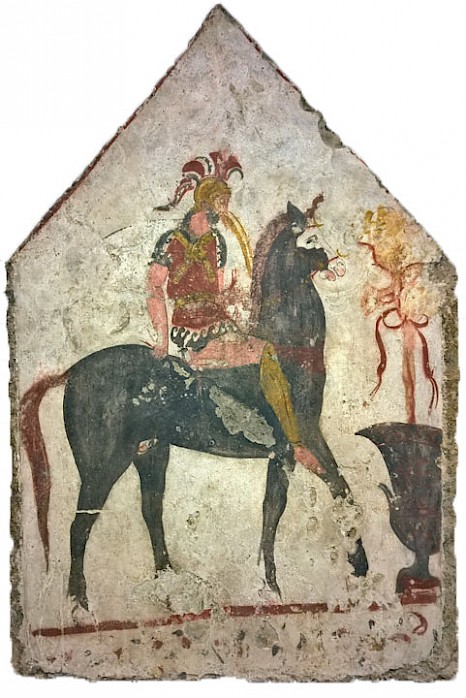

A rider on a black horse is depicted on the slab from Tomb 58 from Paestum. Horses in the Greek world were used solely for riding and for warfare, never as ordinary draught animals, and thus were symbols of the rich. The krater – a large mixing vessel for water and wine – show on the right side of the painting is a reference to alcohol consumption, another important element of the elite lifestyle. The tomb dates from ca. 340 BC.

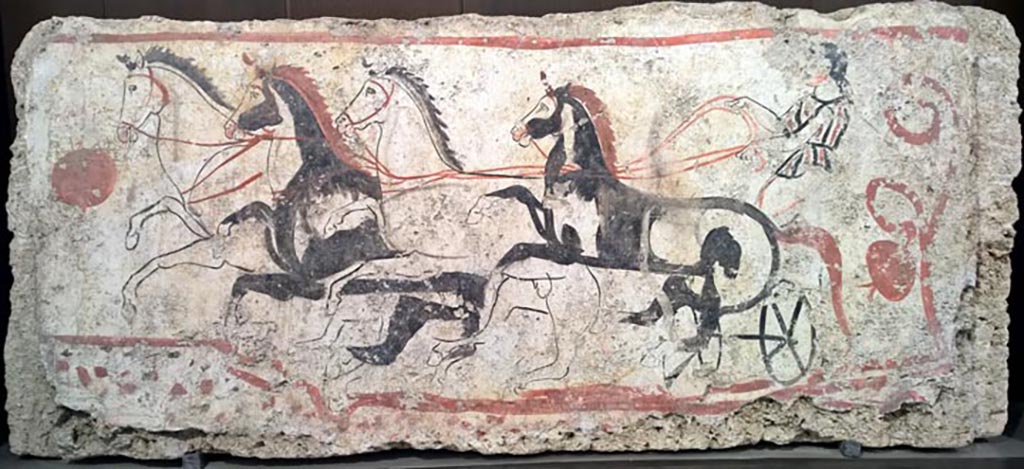

Above is a picture of the southern slab of Tomb 48 from Paestum, dated 340–330 BC. It shows a racing chariot with a team of four horses. Chariots were expensive and chariot races a favourite past time of the rich. Chariot races were already organized by epic heroes in the Iliad and there are hints that such races date back to the Late Bronze Age.

The tomb paintings give us an idea of what life was like in Paestum in the fourth century BC, or at least what the deceased and/or his relatives believed life ought to be. Above is a picture of the northern slab of Tomb 4 from Paestum, which depicts a prothesis scene, i.e. a scene where we see the deceased on a bier (centre), surrounded by some token mourners. A boy at left plays the double flute.

The archaeological site

The excavated area is quite extensive. The city was surrounded by a wall, large parts of which are still visible, along with rectangular Roman watch towers (which seem to be used for storage by the archaeological service or the municipality). The excavated area occupies roughly the middle portion of the walled area, running from south to north.

The site contains the remains of a large open area (the Roman forum and Greek agora respectively, according to the map), dwellings (of which only the stone foundations remain), a swimming pool, monument to a hero, bouleuterion (senate), amphitheatre, and other structures; there are two sacred areas (urban sanctuaries) or temple precincts. The site gives a good idea of what a small Roman town might have looked like that had a history that stretched back to the sixth century BC.

Regarding the temples, there is one in the north, traditionally referred to as the ‘Temple of Ceres’. Then there are two more temples in the south part of the town, flanking the so-called ‘Via Sacra’. The northern one is referred to as the ‘Temple of Neptune’, while the southern one was originally called the ‘Basilica’. The names date back to the eighteenth century; modern archaeological research has revealed further information that allow us to properly interpret the structures. All temples are oriented east-west.

The northernmost temple was originally identified as dedicated to Ceres, the Roman equivalent of Greek Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and fertility. However, excavations revealed a large number of statuettes of the goddess Athena, so that the temple must have been dedicated to the goddess of wisdom and warcraft. It is a Doric temple built around 500 BC. Originally, the pronaos (the portico leading to the main room, the naos or, in Latin, cella) featured Ionic columns. Nearby are also the remains of the foundation of an earlier temple, dated to ca. 580 BC.

The best preserved of all the Greek temples in Southern Italy is the massive “Temple of Neptune” located in the southern urban sanctuary. It is the largest of the temples at Paestum and is generally thought to have been dedicated to Poseidon, after whom the Greeks had named their city (Posidonia). However, it may also have been dedicated to Zeus, Hera, or even Apollo. Nearly all of the constituent parts of the temple have survived. It was probably built in the second quarter of the fifth century BC.

This impressive temple adheres to Classical proportions: there are six columns on the short sides and thirteen on the long sides. The Doric columns, carved from local limestone, are almost nine metres tall, and each has 24 flutes. Inside, a high step leads from the pronaos – with two columns set between pilasters – to the naos. At the back, there is also an opisthodomos, similar to the pronaos, but without offering access to the naos. It was used for storage of votive offerings and the like.

This structure was originally referred to as the “Basilica” on account of the large number of columns on the short sides and the lack of pediments, which led thinkers in the eighteenth century to believe it was used for civil rather than religious purposes. However, it is clear now that it was a temple, and in fact is the oldest of the temples at Paestum still standing. It dates back to the middle of the sixth century BC. It has nine columns on the short sides and eighteen on the long sides. The temple is made largely of limestone, but excavations have revealed that other parts may have been made of softer sandstone, including perhaps the now lost frieze and pediments.

Columns along the long axis of the temple divided the naos in two, which wasn’t strictly necessary for architectural purposes. Finds from in and around the temple suggest that it was dedicated to Hera. Based on the finds unearthed here, men may have worshipped her as a warrior goddess, while women appropriated her as the goddess of birth and growth. The altar has been preserved and can be seen in front of the temple. In ancient times, people practised their religion outside of the temple, not inside (unlike a modern church, for example).

The above photograph shows part of the terracotta elements that once decorated the edges of the tiled roof. The waterspouts have the shape of lion heads, a very common decorative element form the ancient Greek world. During rain, water would run along the roof tiles and be collected at the edges, from where it would flow through holes and leave in a stream from the mouths of the lions. It must have had a wonderful effect.

Closing thoughts

There’s lots more that we can talk about when it comes to Paestum. I haven’t even discussed the beautiful metopes from the temple of Hera at the mouth of the Sele, for example, which include reliefs showing episodes from the stories of Heracles and the Trojan War.

It’s a beautiful site with a fantastic museum, and if you ever happen to be in Southern Italy, you owe it to yourself to pay it a visit. You should also check out the official website.