You fall into a corridor and land in front of a portico carved with an imposing looking face, flanked by statues of six-armed giants, the Gegenees. You face a corridor surrounded by the red waters of the river Styx, the translucent green shades of the dead milling around you. “Goodbye father,” you mutter. Then: “To hell with this place.”

Running through the corridor you smash a few pillars with your Stygian blade before advancing to the next chamber, marked with the image of a shield. Here, the shades are corporeal, glowing orange – and they attack you! First come the Wretched Thugs, their clubs held aloft; next, Wretched Witches, who cast their orange orbs at you. After you destroy them, the shield icon reappears – a message from the goddess Athena, your cousin, here to aid you on your quest with the offer of a boon.

You are Zagreus, Prince of the Underworld, and this is Hades, a video game developed and published by Supergiant Games. The game is a roguelike, in which the player proceeds through randomly generated dungeon-like chambers toward their goal until their character dies. Taking its inspiration from ancient Greek mythology, particularly the stories relating to the underworld, Zagreus’ mission is to escape the realm of Hades, his father, to a new life on the surface. Available in early access since December 2018, the game was fully released in September 2020 to widespread acclaim.

As Zagreus, you have a deceptively simple combat system consisting of an attack, a special, a dash, and cast, the latter of which hurls a long-distance bloodstone at your enemies, which may stick into them. But the Olympian and Chthonic gods you encounter offer dozens of opportunities to customise your skills through stat increases, status affects, and new abilities, including calling upon one of the Olympians to aid you. On top of this are the Daedalus Hammers, which upgrade your weapons. However, these boons and upgrades last only as long as your escape attempt: when Zagreus dies, they are lost.

And die you will. The underworld is a huge system of chambers on multiple levels, each occupied by shades charged by Hades to prevent your escape. With no way to heal himself, Zagreus must keep going until his heath bar runs out and he falls back into that red river Styx.

There is no escape

The year 2020 was a hard one for a lot of reasons. Primarily, there was the COVID-19 pandemic; for those of us employed in “non-essential” jobs, we will remember the instruction to stay home and save lives, whether that meant working from home or being furloughed.

For all the comparisons of the modern pandemic to ancient plagues, it is difficult to escape the fact that for the most fortunate among us this has been one of the best times in history to have been asked to stay at home. 2020 was a year when our streaming services and gaming devices allowed us to have shared experiences despite the necessity of being physically distant.

I’m not much of a gamer, but some knowledge about games filters through my social media feeds from friends, media critics, and scholars of the ancient world who game. From this outsider perspective, I noticed three games dominate 2020. First there was Animal Crossing: New Horizons, released on 20th March, less than ten days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. The life-simulation game gave Nintendo Switch users a chance to socialize and build online communities soon after they were required to stay at home.

The second game that soared in popularity this year was Among Us. Although actually released in 2018, the party game saw a surge in users first in South Korea and Brazil, before being adopted globally as another way of socializing while apart as well as a way for social-media savvy politicians to help younger Americans learn about registering to vote.

Hades was the third and final of these games – probably because of its ancient world theme. Released on 17th September, Hades soon appeared on my Twitter feed from the various people who study gaming and the ancient world. By the end of the year, it was rated among the best games of 2020 by many gaming publications such as Polygon, and had the second-highest number of nominations at The Game Awards 2020, including two wins.

As a single player game, it does not quite fit my narrative of the other two games that encourage socializing through their mechanics. So, what resonates so much about Hades? We should not discount its smooth gameplay and crisp graphics – the game looks fantastic, and it was screenshots shared on Twitter that originally piqued my interest.

But at its core the game is a story about an individual, trapped in his father’s house, desperately trying to escape to the surface, to sunlight, to freedom. It sounds like a common Millennial life experience in any given year; in 2020, this was only intensified. Critic Carolyn Petit described it on Twitter as “the right game at the right time” for its resonance with current events.

As I said, I’m not much of a gamer. My touchpoints for the medium are the ’90s and early ’00s: Final Fantasies VII through IX; the earlier Sonic the Hedgehog games; Mario Kart and Super Smash Bros. In the light of a pandemic, and the impending remake, I joined Steam to replay Final Fantasy VII this year; it was perhaps doing so that revealed to me that I might, in fact, have space in my life for Hades as it began to infiltrate my Twitter feed. Mentioning this on Facebook, a friend gifted me the game on the basis of its reputation. I had to expand my laptop’s rather meagre SSD to even install it.

The point of this background is to say that I am not the target audience for this game. I am not the target audience for any game. And yet, here I am, hours deep into Hades, still struggling to fight my way out of its underworld.

Blood and darkness

You trudge up the stairs out of the Styx, into a familiar looking corridor occupied by more translucent green shades. That imposing looking face looms down on you from the wall again. You’re back in the House of Hades.

As you enter the house, you awaken Hypnos, god of sleep, who offers some comment about how quickly you returned this time. Ignoring him, you turn to the infernal, three-headed watch-dog that salivates in the corner awaiting his next meal. Obviously, you pet Cerberus – he’s a good boy. A voice beside you scoffs. It’s that imposing face again, this time in person: your father, Hades, god of the dead. He sneers at your attempts to escape. No one gets out of his realm without permission.

Failure is a key part of Hades. The game seems to take its core philosophy from Samuel Beckett’s “Worstward Ho” (1983): “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Every time Zagreus “dies”, he returns to the House of Hades to regroup and prepare for the next attempt. Here is where you can make permanent upgrades to your skills, but also take the opportunity to talk to the various characters that occupy the House and so advance the many subplots within the game.

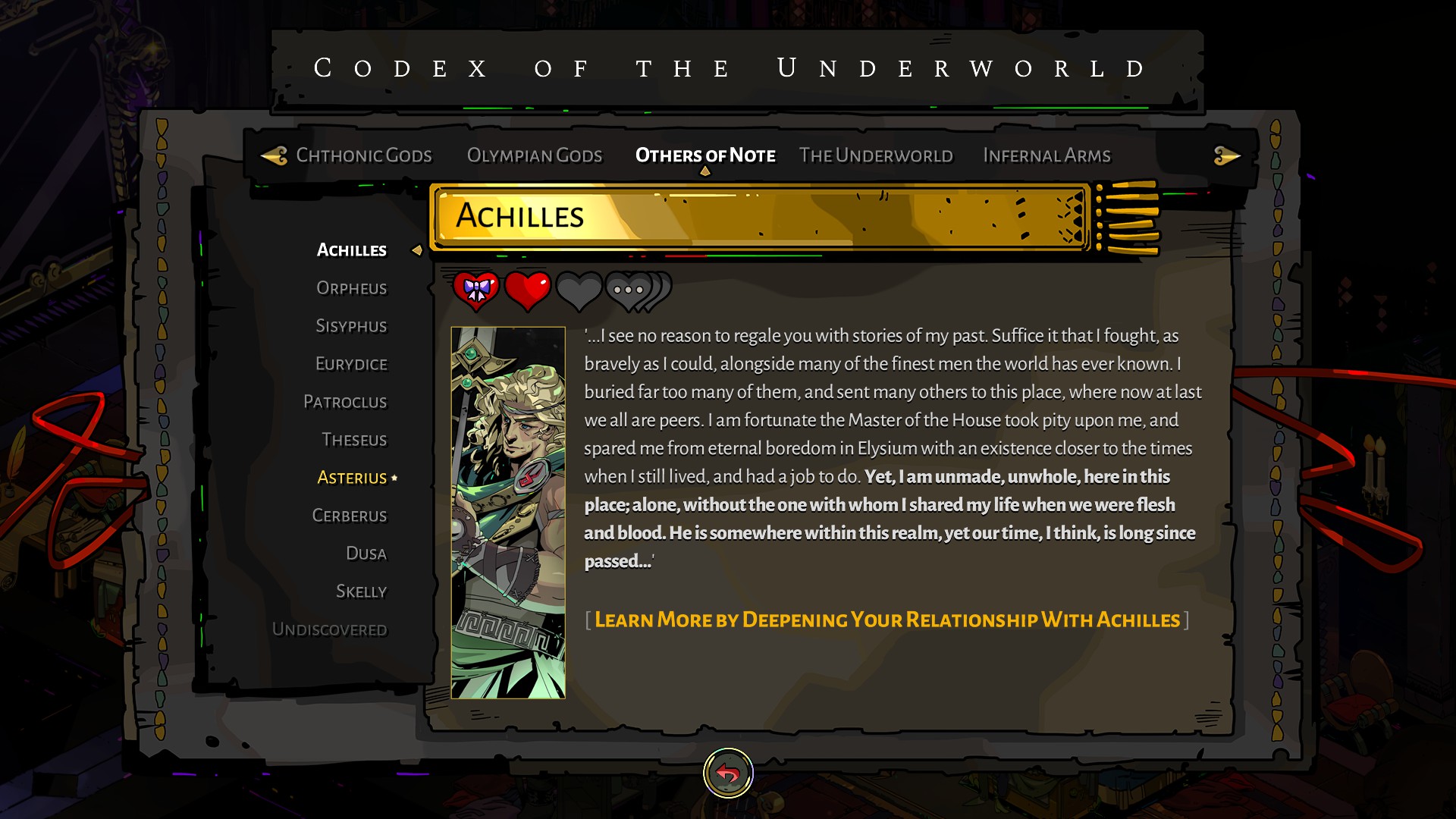

In the West Hall of the house you will find Achilles standing guard, keeping his watchful eye on the denizens of the underworld. You soon discover that Achilles trained you, hence Zagreus’ skill with the sword; he also provides you with the Codex that you will use to keep track of the shades you fight and the people and things you encounter while you attempt to escape. It also becomes apparent that Achilles has lost the great love of his life, who must be somewhere in the underworld, surely?

In the East Wing, outside Zagreus’ bedroom, stands Nyx, primordial goddess of the night. You have been led to believe that Nyx is your mother – certainly the Olympian gods believe this to be the case – and she is supportive of your attempts to fight your way out of the underworld. She has provided you with a mirror in your bedchambers where you can use the darkness that you collect on your escape attempts to upgrade your skills: more health; stronger attacks; better recovery.

As you return to the House of Hades over time more characters appear: Dusa, the hard-working gorgon hired by Hades as a cleaner; the House Contractor who will take gems to complete work orders that change things in the underworld as you escape, as well as making aesthetic changes to the House. When the lounge opens, you can trade items with the Wretched Broker. Some of the figures that you defeat on your escape attempts also make it back to the House; others, such as Orpheus, you can free from captivity – for a price.

Failure, of course, is a key part of Orpheus’ tale of trying to escape the underworld with Eurydice. While exploring Tartarus you may also encounter the up-beat Sisyphus, who tries over and over again to push a boulder up a hill but never succeeds – punishment for trying to cheat death and escape the underworld. Supergiant Games clearly know how to make their story thematically resonant with their ancient inspiration.

As you talk to people, your familiarity with them grows and the Codex Achilles gave you fills up with information about them. The process can be expedited by sharing Nectar, found on your travels, with people you like. Some of them will grant you keepsakes with different effects that you can carry with you on your escape attempts.

Zagreus never stays home for very long. Soon you will want to head out through your bedroom to the training area, where you can select one from up to six weapons to take with you on your next attempt: traditional Greek fare such as sword, spear, shield, and bow; the “Twin Fists of Malphon” that allow you to fight hand-to-hand; and the horrifying Adamant Rail. Skelly, your immortal punching bag, will allow you to test your skills with the weapons on him before you make your way out into the underworld. Time to fail better.

Codex of the Underworld

The Megagorgon’s head rises from the ground of Asphodel, the yellow glow around it indicating that she is shielded. She is several times the size of the miniature gorgons that you have seen floating around the Phlegethon-flooded islands, and, like them, she spits petrifying rocks at you. While you can free yourself by dashing, her Skullcrusher companion may take the opportunity to fall from the sky and crush you.

Hades takes what I would call the sensible approach to utilizing Greek myth in the contemporary world: the myths serve as a guide, but one that need not be followed too closely. Several of the game’s bosses are monsters and heroes from Greek myth, but the majority of the enemies you will fight are typical dungeon-crawler fare.

In Hades’ take on the myths, gorgons are disembodied heads with snake-hair, born from the blood spilled when Dusa’s head was severed from her neck. The dead Lernean Hydra is now a skeleton that spawns new heads at certain fixed points, but once each one is defeated, it’s gone for this battle. It’s not quite the monster as we know it, but it works.

The background detail of the game also draws on Greek art and archaeology. Varieties of skeleton warriors wear Corinthian-style helmets with crests running ear-to-ear. A more familiar style of this helmet sits in Zagreus’ bedroom next to the skull of a gorgon. The warriors of Elysium carry the typical weapons of Greek heroes – swords, shields, spears, and bows – although, like Zagreus, they only use one at a time. The bodies of these warriors are also decorated in a style reminiscent of bronze body armour as depicted on black-figure vases. The Greatshields carry what appears to be a Boeotian shield – a kind of shield depicted on Greek vases from the seventh century BCE that is almost identical to the double-grip aspis, but with two crescents cut out on either side.

Up to a point, the architecture also draws upon ancient Greek styles and there are numerous Corinthian columns, reliefs, and vases drawn from the archaeological record throughout the underworld. Dr Kira Jones has outlined these in a series of epic Twitter threads so I won’t go into all the details, but you can check those out here, here, here, and here. Fundamentally, the designers of Hades know their stuff but are not bound to accuracy. They are not trying to replicate the ancient world, but they are clearly inspired by it.

It is not only the look of Hades that is enriched through reference to the ancient world, but its story – or, more particularly, the many different stories that are woven together around Zagreus’ escape attempts. Central is the relationship between Zagreus, Hades, and Nyx, the latter of whom helped raise Zagreus as if she were his mother – as the Olympian gods believe she was. Zagreus’ relationship with his father is tense even before his attempted escape from the underworld; the current situation is prompted by Zagreus’ discovery of a secret about his mother that has been kept from him his entire life.

For those troubled by contemporary interpretations of Hades and Persephone’s relationship as the height of romance, Hades offers something more complex. Persephone is a hollow absence in the underworld of the game; Zagreus has never even met her. Hades himself is sullen and alone; an angry, bitter man – no romantic hero. Details about their relationship come sparingly throughout the game, but it is never romanticized.

The Olympian gods appear largely at a distance, sending Zagreus messages and vaguely aware of where he is, but unable to hear what he has to say. Their personalities are broadly drawn and based more on their attributes than their character in ancient literature or religion, but immensely enjoyable: Athena is proud, Dionysus bawdy, Aphrodite flirty, and so on.

Their personalities and attributes also shape the boons they grant you. Zeus will strike your enemies with lightning. Aphrodite makes them weak at the knees. Hermes will make you faster. They also offer some delightful puns based on their attributes and the skills they offer, especially Poseidon who talks about steering your ship, helping you weather the storm, and even more ocean-themed wordplay.

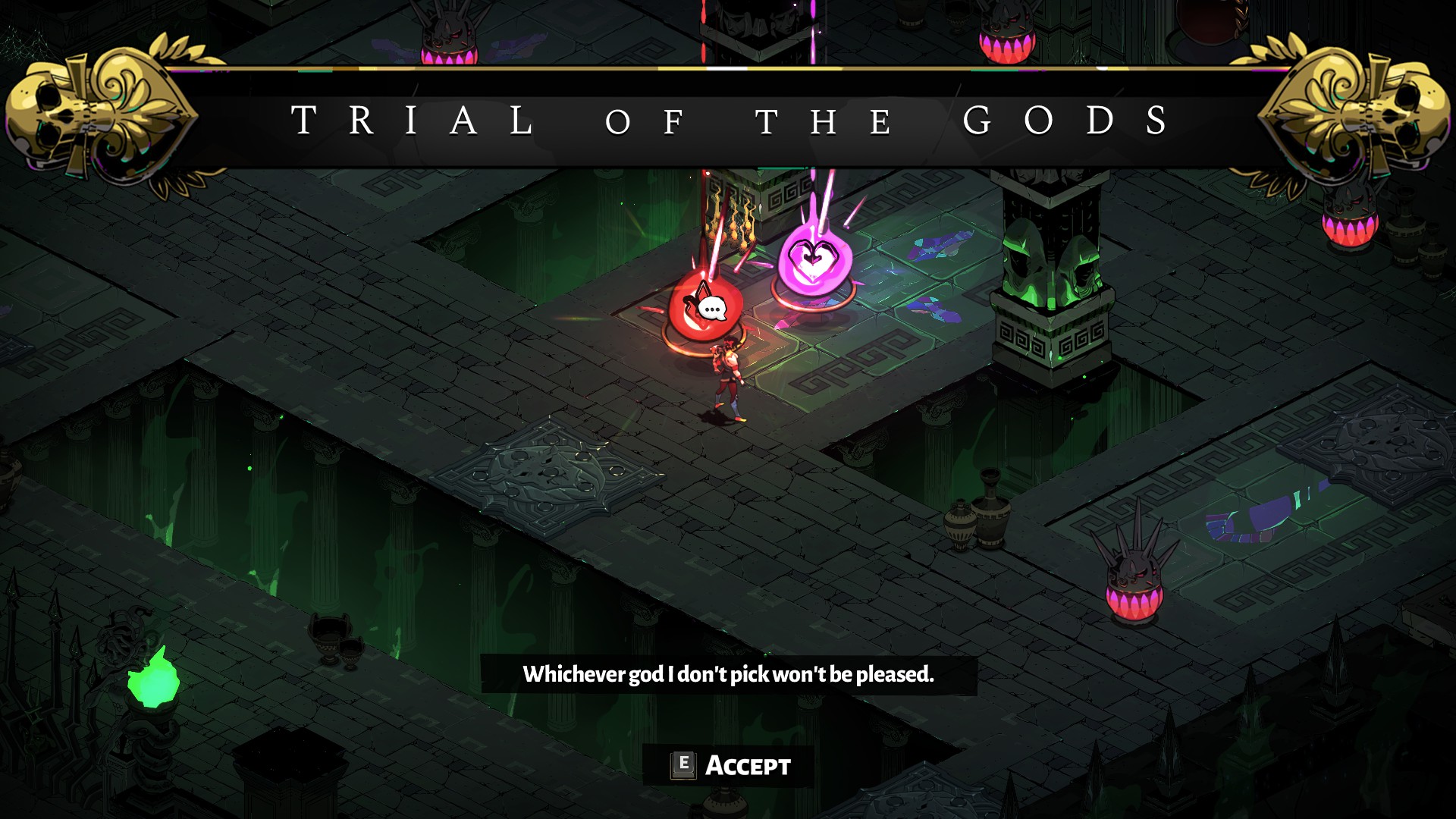

These gods are also jealous. At times, Zagreus will be offered the choice of a boon from one god or another and whomever you do not choose will not take it lying down – expect not only a fight, but one backed up with the god’s power. They will forgive you – eventually – and you’ll exit the chamber with two new boons if you survive.

On the Chthonic side the gods offer different kinds of assistance. Primordial Chaos follows your adventures with curiosity, offering rewards for surviving a number of chambers with some kind of restriction on your abilities. After a while, Thanatos, god of death, will appear to begrudgingly offer his assistance dooming the shades that attack you. And Nyx constantly offers her support, allowing you to grow stronger through her mirror and your collected darkness.

The heroes and heroines of myth offer subplots connected to the familiar stories about them. The more you get to know Eurydice and Orpheus, the more you discover about their lives together and how they feel about the bard’s previous attempt to rescue the nymph. You may even take it upon yourself to find a way to reunite them.

Besides the ancient world, Hades also mixes in some references to more recent takes on ancient myth – some clear, some I may have imagined. At one end of the spectrum there is the mechanical owl that accompanies Athena, an obvious allusion to Bubo from the movie Clash of the Titans (1981). Somewhere in the middle is the decision that among their racially diverse cast of gods Athena should have black skin – a reference to Martin Bernal’s controversial 1987 book Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization?

At the far end is what I brought to the game myself: I started playing Hades alongside watching classic 1990s television show Xena: Warrior Princess (1995-2001) and I found myself spotting things that seemed familiar. The way Zagreus throws the aegis, also called the Shield of Chaos, is clearly influenced by Marvel’s Captain America; but am I imagining a little bit of Xena’s chakram in there too – especially the multi-shield throw of the Aspect of Chaos and the mid-flight splitting of the Chakram of Balance? How about the “Pressure Points” boon offered by Artemis, whose design recalls Xena’s Amazons? Is it too far to suggest that Hades’ disgust at the hero Heracles relates to the fall-from-grace of Xena’s Hercules, Kevin Sorbo?

Ancient Greece has been a subject of reinterpretation and retelling for so long that it may be impossible to untangle all the interconnected influences on any given new story. Part of the fun of thinking about these things is the many different ways in which we can imagine information about the ancient world coming to different creators, as well as what we bring to it ourselves as casual viewers or players.

But there’s only so long you can spend admiring the reception in Hades. Spend too long admiring the reliefs of Danaids in Tartarus or the statues of fully-armed Greek warriors in Elysium and some shade will take the opportunity to stab you in the back, and then it’s time for Zagreus to return home.

Death approaches

After returning once again to the House of Hades after yet another escape attempt, you see Orpheus has gone over to speak to Achilles at his post in the West Hall. Curious, you listen in on what they have to say – they are talking about work. Orpheus says:

I am profoundly satisfied. We are most fortunate to have employment even after death. Imagine, merely resting for eternity, when you could work!

Life-after-death in Hades is a slow-moving, tedious bureaucracy. Hades himself is usually sat at his desk doing parchmentwork, scrolls piled up all around him. Zagreus, we learn, was utterly terrible at this work, leading his father to fire him. But several figures from myth are fortunate to be employed at a time when others are not.

Not everyone shares Orpheus’ enthusiasm for work. In the lounge, you may encounter various characters relaxing as they enjoy the Nectar you have shared with them. Sometimes, the Fury Megaera is having a girls’ night with Dusa, where the gorgon advises her:

I just mean, if you don’t believe in the work you’re doing, why keep on doing it, just out of obligation? You have to take care of yourself.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted many of the injustices in our living world of work, from the initial shift to work-at-home that was denied in pre-COVID times to disabled workers who needed it, to the realisation that most of our “essential” workers are those paid at or near the minimum wage, right through the insufficiency of most sick pay, an essential factor in any pandemic response.

Individual industries have their own workplace issues. To an outsider, the biggest concern in the gaming industry appears to be the toxic culture of “crunch”, the forced overtime to meet studio-imposed deadlines that ends up contributing to disasters like the Cyberpunk 2077 launch. In all walks of life, it should be clear that people need time off, and happy workers are good workers.

It seems that work may be one of many underlying themes in Hades precisely because the study behind it, Supergiant Games, is aware of these issues. In a 2019 interview with Kotaku, two of the members of their team argued that the secret of the studio’s success is that everyone is happy working there. The company is focused on employee health and personal growth. Its culture, as described in the article, is aspirational: a minimum amount of time off; no emails after 5pm on Friday; creating an environment where everyone can do their best work.

Hades is a direct result of this culture, and it is a fun, engaging, heartfelt game that weaves a deep story into its gameplay mechanics. The individuals in the studio behind it clearly believe in what they are doing, and take care of themselves. Why work yourself to death if the only joy afterwards is work?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Matt Marshall for gifting me Hades. I didn’t know I would end up playing it this much.

Further reading

Hades was declared “Game of the Year” in several publications, including Polygon, IGN, and Ars Technica. Forbes has a list, here.

Kotaku’s interview with Amir Rao and Greg Kasavin of Supergiant Games.

An in-depth look at the use of mythology in Hades is available in this YouTube video by History Respawned with Dr Kate Cook.

For a serious take on race in Hades, read this piece in Kotaku; for a less-serious take, try this piece in The Hard Times.

For a critical look at masculinity, sexuality, and disability in Hades, see this article in Wired.

Much has been written on the Black Athena controversy. Dr Rebecca Futo Kennedy handily sums up Bernal’s achievements on the YouTube channel The Study of Antiquity and the Middle Ages thus: “Does he stand up? Parts of his model still stand up, but […] only because archaeologists had been doing that work already for decades” (September 2020).

Denise Eileen McCoskey discusses the legacy of the response to Black Athena in the field and touches on its reception beyond in this article for Eidolon (November 2018).