Back in 2013, as I was finishing my doctoral thesis, I visited one of the Greek archaeological museums that had eluded me for nearly a decade: the Nafplio Archaeological Museum in the Argolid. This museum houses finds from across the Argolid including Nafplio itself, Asine, and Tiryns (Argos and Mycenae have their own museums).

Among the finds were a set of cups from a grave in the Tiryns Philaki Cemetery. Cist Grave 23 contains three burials from throughout the Early Iron Age; the latest was added on top of the cist in the second phase of Late Geometric, i.e. ca. 730-690 BC (Verdelis 1963, pp. 35-40).

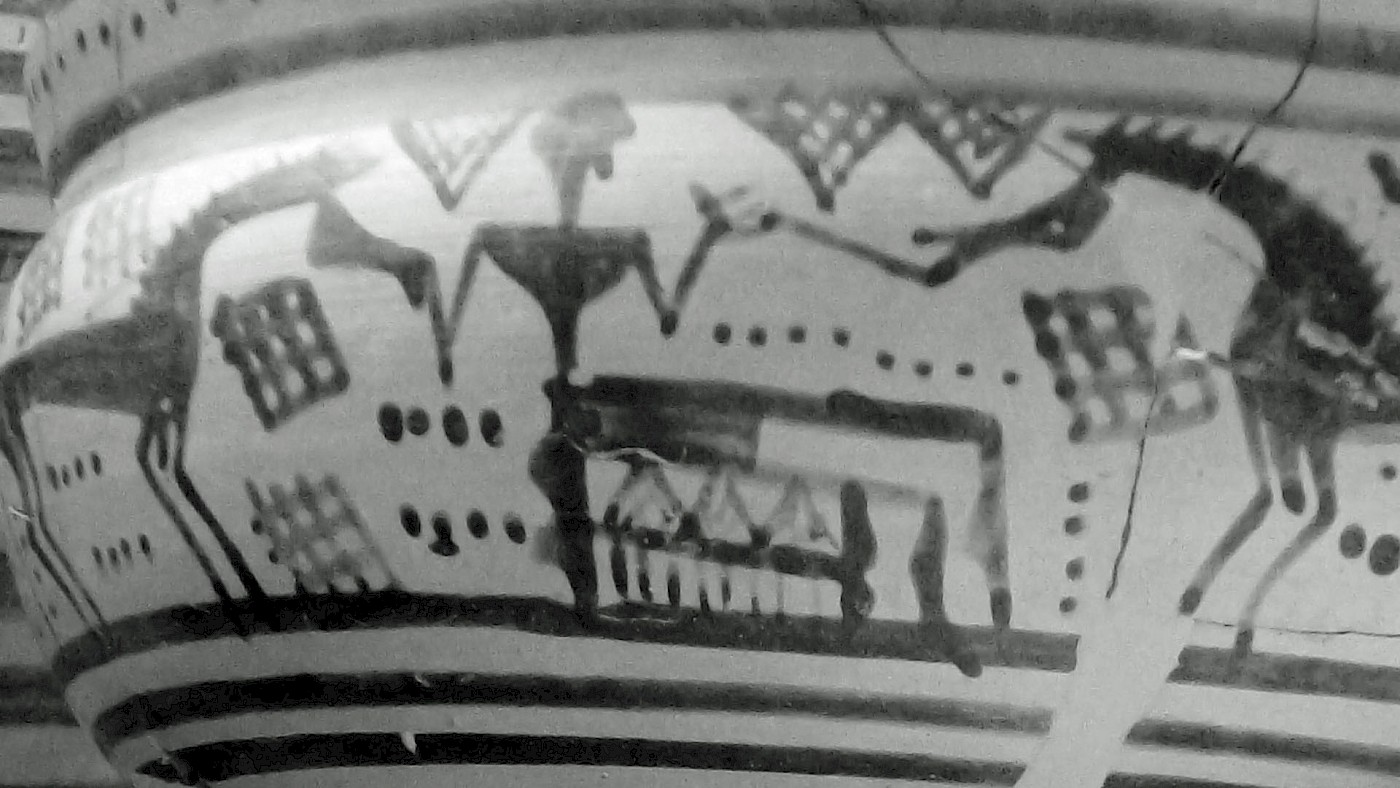

The cups in question show a familiar scene of Late Geometric vases from the Argolid: the Master of Horses or “Horse-Leader”, a man holding the reigns of either one or two horses. But one of these Horse-Leaders is unusual: a long, decorated platform sticks out from behind him, filling the space between the man and the horse. It looks like an early centaur.

Early centaurs

The earliest depictions of centaurs are not like those we know in the Classical period. By the fifth century BC, centaurs are often shown as wild, beast-like creatures that fight men and rape women. Certainly, by the seventh century BC, the story of Herakles slaying Nessos after his attempted rape of Deianeira is known on vases from Eleusis and Thebes; in the fifth, their battle with the Lapiths at the wedding of Perithous was depicted on the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and the metopes of the southern side of the Parthenon in Athens.

But the earliest centaurs show a different side to the half-man, half-horse creatures. In the tenth century, the Lefkandi Centaur can plausibly be identified as Chiron, who trained the heroes Heracles and Achilles. The head of this figurine was found in the grave of a child while the body was in a different grave, belonging to an adult. It has been suggested that this indicates a pedagogic relationship between the two deceased individuals (Langdon 2008, pp. 71-73).

By the eighth century BC, very little appears to have changed. On Attic vases, Centaurs are shown in wild areas, existing between civilization and the natural world, and no known vase shows them fighting or violent at all. Susan Langdon argues that these Attic Centaurs show “positive masculine traits”, as they were creatures which trained young boys to be men (Langdon 2008, p. 106).

Centaurs are known on about fourteen Attic Late Geometric vases. When I asked Twitter what it thought about my identification of the Tiryns Horse-Leader cup, Dr Jessica Doyle, an Early Iron Age iconography expert at University College Dublin, told me that they are almost unknown in Argive Late Geometric. The exception is a shield in a bothros (offering pit) on the former palace site at Tiryns, usually dated to the early seventh century BC. This cup was certainly unusual.

The Master of Horses

The centaur’s significance in Late Geometric art is connected to the ascendant importance of another status symbol in Archaic Greece: the horse. It appears on Late Geometric pottery throughout Greece by itself, leading a chariot, or in the “Horse-Leader” group, but this particular motif is most popular in the Argolid.

The Master or Mistress of Animals motif is known in Bronze Age iconography. But with the disappearance of figurative art at the end of the twelfth century BC (at least, in archaeological preserved form), these figures are unknown for the first centuries of the the Early Iron Age.

The horse is a fierce wild animal, but one that can be tamed. Langdon interprets the resurgent Master of Animals motif as a symbol for the taming of the natural world by human beings, describing the Horse-Leader in the Argolid as “the quintessential symbol of status and excellence” (2010, p. 127). Indeed, there are many depictions of the Horse-Leader among the vessels in Tiryns-Philaki Grave 23.

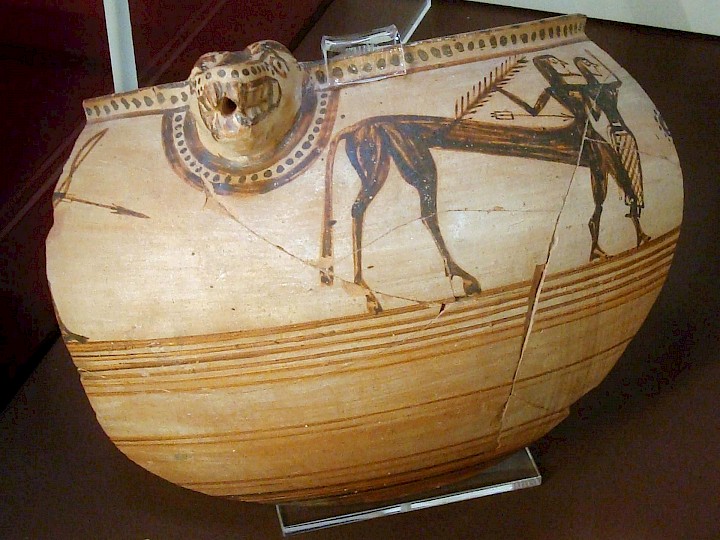

Another interesting depiction of the Horse-Leader appears on a kantheros adjacent to the potential centaur/Horse-Leader in the display case of the Nafplio Museum. (The museum label attributes this vase to Grave 23, but the vase is not illustrated alongside the other cups in Verdelis 1963.) On this vase, the Horse-Leader is a warrior with a Dipylon shield, holding the reigns of two horses, flanked in turn by two duck-like birds.

Twitter user @keftiugal pointed out to me that this vase is completely devoid of the filler-motifs that we usually find on Late Geometric vases – including the other Horse-Leaders – and that the precision of the lines seems to foreshadow the outline and black-figure wares of the next century. Compared to this vase, the others look rushed and imprecise.

An accidental centaur?

The Horse-Leader/centaur figure does not look much like other Late Geometric Centaurs. His body does not look like the horses which he leads, it is only half painted, and his feet face the wrong way. (On Late Geometric pottery sherd from the Argive Heraion the bottom half of four figures have been preserved, the larger two of which have doubled feet – see Ahlberg 1971, p. 15. Ahlberg interprets this doubling as evidence that the full figures would have been monsterous. If so, it is possible that the wrong-facing feet of this “centaur” also indicates that the figure is monstrous.) But it is difficult to think of an alternative interpretation.

Jessica Doyle alerted me to another depiction of a centaur, this time from Boeotia, currently held by the Canellopoulos Museum in Athens. On this vase a pair of phantom legs beneath the horse-body of the centaur has led to the suggestion that the artist intended to paint a man and a horse but, running out of room, converted them into a centaur. (The publication of this vase, including a picture, is available for free online here. See also Langdon 2008, p. 105.)

This particular vase made me think of a section of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura (IV. 739-743), in which he explains that Centaurs were imagined by the combining of a simulacra of a man and a horse:

nam certe ex vivo Centauri non fit imago,

nulla fuit quoniam talis natura animata;

verum ubi equi atque hominis casu convenit imago,

haerescit facile extemplo, quod diximus ante,

propter subtilem naturam et tenvia texta.

In English translation (modified after the English version found on the Perseus website):

For soothly from no living Centaur is that phantom gendered,

Since no breed of beast like him was ever;

But, when images of horse and man by chance have come together,

They easily cohere, as I said before,

At once, through subtle nature and fabric thin.

I wonder if the painter of the Tiryns centaur/Horse-Leader encountered the opposite problem to the painter of the Boeotian vase: having placed the horses slightly too far apart, there was a greater space to fill on this vase than originally intended. Rather than use even more filling motifs, the artist attempted to paint the monster popular among Attic painters at the time that might not have been so well-known in the Argolid: the centaur.

Conclusion

Late Geometric vase painters took their inspiration from a great variety of different sources, from their own past, rediscovered in tombs across Greece, to the ever more accessible Near East. But in some cases, necessity may have been the parent of invention. Artists had different reactions to the space on their vessels, from the need to fill them, through correcting mistakes, to leaving them blank. Perhaps this Tirynthian artist made a mistake and tried something new.

Further reading

- G. Ahlberg, Fighting on Land and Sea in Greek Geometric Art (1971).

- S. Langdon, Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100-700 BCE (2008).

- S. Langdon, “Where the wild things were: The Greek Master of Animals in ecological perspective”, in: D.B. Counts and B. Arnold (eds), The Master of Animals in Old World Iconography (2010), pp. 119-134.

- N.M. Verdelis, “Neue geometrische Gräber in Tiryns”, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung 78 (1963), pp. 1-62.