Located only a few kilometres from Phaistos is the archaeological site of Agia Tradia. You can easily drive there from Phaistos. You can park at the top of the hill and then have to take a flight of steps down to get to the ticket office. There’s a platform here where you can sit in the shade and have a drink or a bite to eat – provided that you brought something along yourself as there’s not much to buy here.

The archaeological site of Agia Triada was first explored in the early decades of the twentieth century. The Italian School has been conducting systematic excavations since the 1970s and much of the town that once existed here has been unearthed. The site is located on a hill, close to Phaistos, the Geropotamos River, and the harbour town of Kommos (north of Matala). The hill is located on the western edge of the fertile Messara Plain, as is obvious when you’re at the site.

We don’t know what the site was called in ancient times: it’s possible that it was simply considered a part of Phaistos (La Rosa 2010, p. 497). Agia Triada (“Holy Trinity”) is the modern name, also transliterated as Hagia Triada or Ayia Triada. When you visit the site, you’ll see a small church near the edge of the site dedicated to St George Galatian. The church was closed when we were there, but it dates to the fourteenth century BC and inside the apse features beautiful Byzantine wall-paintings behind the altar that can be glimpsed through cracks in the door.

An important town

The site appears to have been occupied first during the Bronze Age and its extent seems to have been limited throughout its history until its final destruction at the hands of Gortyn in the second century BC. In the Bronze Age, Agia Triada was a Minoan town that flourished from about 2000 BC onwards, with pottery indicating social differentiation. Vincenzo La Rosa believes that the histories of Ayia Triada and nearby Phaistos were intricately bound up with each other, suggesting that “At the beginning of MM IB [= Middle Minoan IB, Protopalatial, say around 1900 BC], workers and elites could have been involved in the construction of the nearby palace of Phaistos” (La Rosa 2010, p. 498).

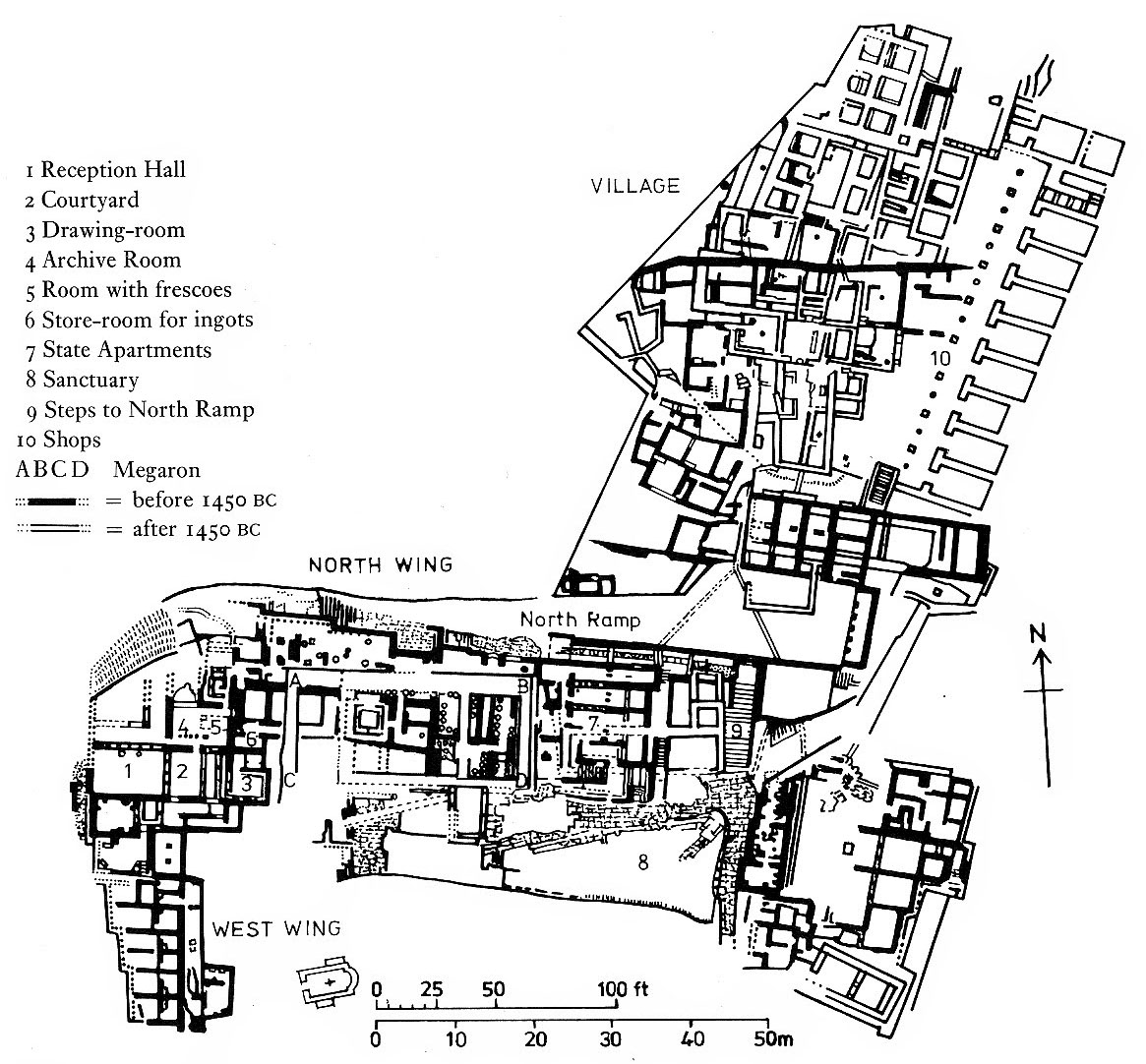

During the Neopalatial period, ca. 1750/1700 to 1470/1460 BC, Agia Traida reached its zenith with the construction of a Minoan “villa”, a roughly L-shaped palace-like structure. The villa was located on a higher plateau of the hill and separated from the slightly lower town area by a monumental structure. La Rosa suggests that the founding of the villa “was a political action favored by the Knossian elite at a time in which the Phaistian palace was not in use (between MM IIIB and LM IA)” (La Rosa 2010, p. 499). Knossos may have tried to exert its influence over the Messara Plain by constructing a satellite here in a period when Phaistos had been (temporarily) abandoned after an earthquake, leaving a power vacuum (see also Younger and Rehak 2008, p. 150; McEnroe 2010, p. 100).

Nearly 150 Linear A tablets, lots of sealings, and objects with inscriptions were recovered from the villa, suggesting that it indeed became an administrative centre during this period, replacing Phaistos. The texts, which are only partially understood, include references to workers, including what appear to be bronze workers, who seem to have worked in exchange for food as they are apparently given rations of wheat, figs, and wine (La Rose 2010, p. 500, with references). Goods were stored at the site and finds of daggers, spearheads, and javelin points suggest that they were well protected. We know that, among other things, almonds and pistachios were kept at Agia Triada (Dickinson 1994, p. 47).

Destruction and change

Toward the end of Late Minoan IB, the very end of the Neopalatial period, Agia Triada was hit by disaster and destroyed by fire, probably after an earthquake. Many sites throughout Crete – including all the palaces – were destroyed around the same time. There is then clear evidence of Mycenaean influence at the site, after the Mycenaean occupation of Knossos in Late Minoan II to Late Minoan IIIA1. Tellingly, a Mycenaean-style megaron (a more or less square room with hearth and fronted by a portico) was constructed directly on top of the Minoan villa (see also McEnroe 2010, pp. 128-132).

On the lower plateau of the hill, in the area of the Minoan town, a Mycenaean town emerged with a square that’s generally referred to as an agora. Small rooms are built along the eastern edge of the agora, in front of which is a line of alternating square pillars and round columns, an architectural feature that is familiar from Neopalatial structures, including the Central Court at Phaistos. In Late Minoan IIIA2, the site underwent changes that suggest an increase in its regional importance and can perhaps be used as an argument for the date of the destruction of Knossos during this period (the so-called “high” chronology; La Rosa 2010, pp. 504-505).

The settlement of Agia Triada, as well as associated tombs, have yielded a rich assortment of important artefacts that shed light on the lives of the people who lived here. Three of these objects will be discussed in articles to be published in the course of the next few weeks: the painted Agia Triada sarcophagus, the Harvester Vase, and the Chieftain Cup. So yes, there’s plenty more to come with regards to Minoan Crete!

Further reading

- Costis Davaras, Phaistos, Hagia Triada, Gortyn: Brief Illustrated Archaeological Guide (2018).

- Oliver Dickinson, The Aegean Bronze Age (1994).

- Vincenzo La Rosa, “Ayia Triada”, in: Eric Cline (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean (2010), pp. 495-508.

- John C. McEnroe, Architecture of Minoan Crete: Constructing Identity in the Aegean Bronze Age (2010).

- John G. Younger and Paul Rehak, “The material culture of Neopalatial Crete”, in Cynthia W. Shelmerdine (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age (2008), pp. 140-164.

Gallery

Inside the Minoan villa

This photo was taken in the southern part of the hill, in the upper area of the remains of the Minoan villa. A Mycenaean megaron was built right on top of these Minoan remains. One of the striking things about this palace-like structure are the many drains, including rock-cut channels, that the builders added to regulate the flow of water through the complex.

The lower parts of the villa

A view from above of the lower parts of the villa, along the south-western edge of the hill. The more or less triangular area in the top left is referred to as the “Court with Colonnades” in the guide book, an open area with a commanding view of the Messara Plain below. The room in the foreground is the “Room of the Sealings”. Clearly visible are the door-and-pier partitions that separate this room from the one next to it, toward the bottom right corner of the photo, which contained remains of a wall-painting of a wild cat. The lower left corner of the photo shows part of a room with colonnades.

A partially restored room

This is a view inside the “Room with the Benches”, so named because of the benches that line three of the walls. Access to this room was again made possible thanks to pier-and-door partitions, which allowed whoever dwelled in this structure to open or close doors to let in, or keep out, light and air. It looks similar to the so-called “Queen’s Megaron” at Phaistos. Perhaps guests were asked to wait here or whoever lived in the palace used this cool room to relax.

The stairs from the agora to the villa

A monumental stair case, photographed from the north, leads from the Mycenaean agora and town up to the higher plateau of the hill, where the villa and (later) the Mycenaean megaron were located. The difference in elevation no doubt served a useful role in distinguishing the site’s administrative (and elite?) structures from the regular dwellings.

A view of the agora

This photo, taken from the southeast, gives an idea of the layout of the Mycenaean agora. Note the smallish rectangular rooms that line the agora. The bases of the rectangular pillars are clearly visible; in between each of them was also a round column. An alternating line of square pillars and round columns is a typical Minoan architectural feature, indicating the limited usefulness of drawing strong borders between what’s “Minoan” and what’s “Mycenaean”.