The ancient Greeks used a variety of pottery in different shapes and sizes. Each type of vessel had a particular use. The original names for most of these types of pots are lost. Even in instances where a vessel is referred to in a text it’s not always clear which type of vessel known from the archaeological record it’s supposed to be, as ancient authors seldom if ever bothered to describe them.

The ancient Greeks were also notoriously – and frustratingly! – inconsistent when it came to terminology. Still, modern researchers need to be able to catalogue ancient objects and so archaeologists have given names to every type of vessel that has been unearthed in excavations and put on display in museums. Hence, a jug can be referred to as an olpe or an oinochoe.

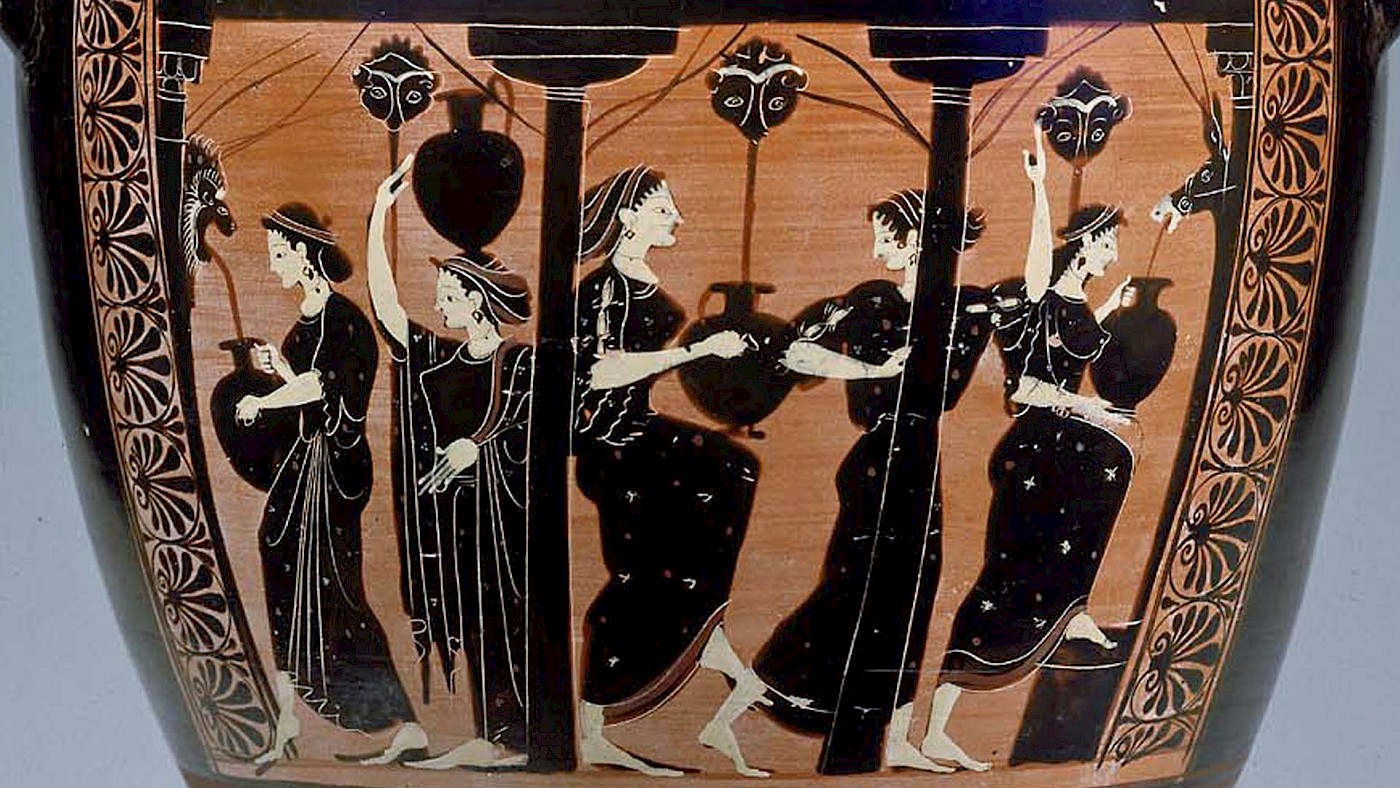

My focus here is one type of pot in particular: the hydria (plural, hydriai). As the name suggests, the hydria was a vessel used for storing water. It had three handles: two oriented horizontally and opposite each other at the level of the pot’s shoulders. These horizontal handles allowed the pot to be lifted up and carried. But a hydria also had a third handle, a vertical one, spaced between the two horizontal handles. This third handle would have allowed someone to more conveniently pour the water from the vessel’s interior. A water jar without the third handle is known as a kalpis.

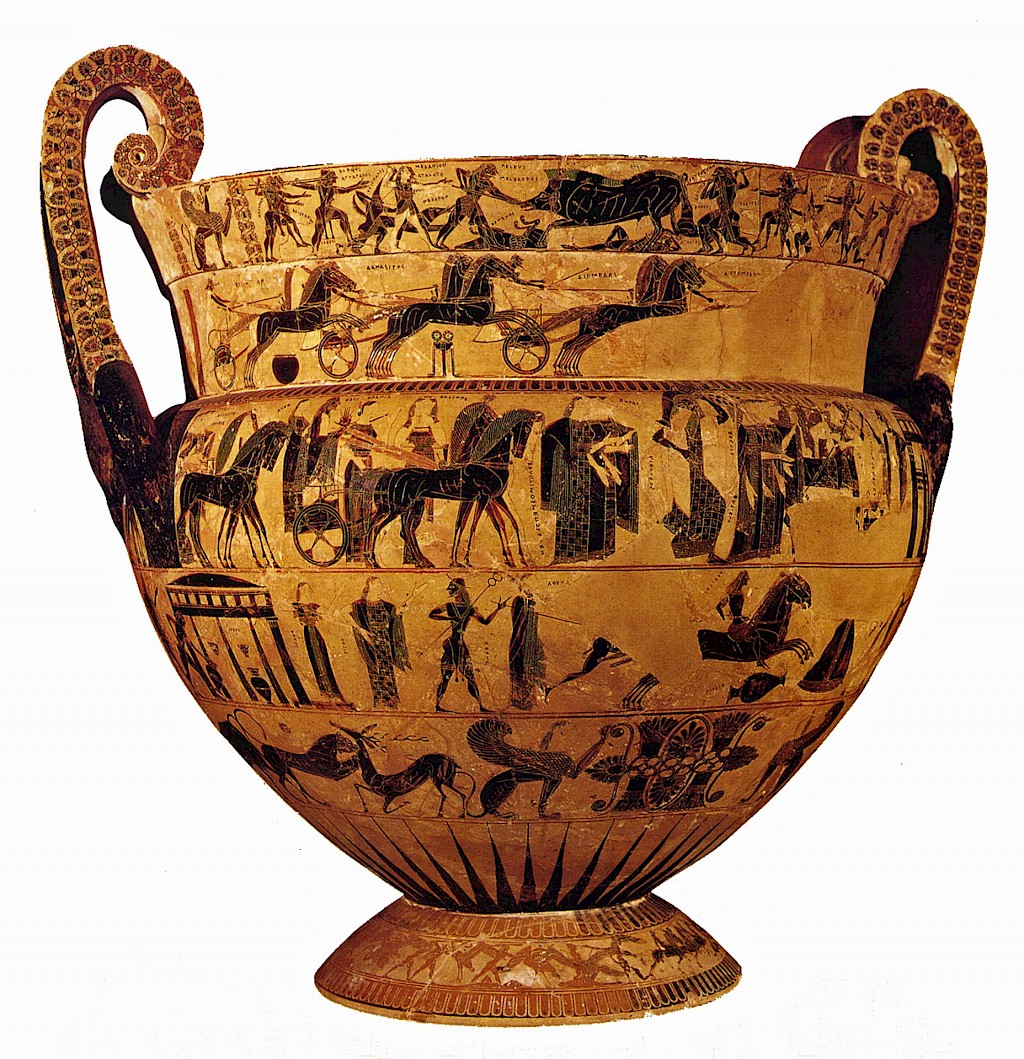

The name, hydria, is actually ancient: a vessel of this type is depicted and conveniently labelled on side B of the so-called “François Vase” (ca. 570 BC). This large pot is actually a krater, used for mixing water and wine, and depicts a number of scenes drawn from ancient Greek mythology. The hydria is shown fallen over on the second figurative frieze from the bottom, in a scene that features Achilles’ ambush of the Trojan prince Troilus. There is a fountain house at the extreme left, the place where Achilles had set up his ambush, and where other jars are shown being filled with water.

While hydriai could be lavishly decorated, using black- or red-figure styles, plain versions were probably much more commonly used. The decorated hydriai would have been brought out during special occasions. For example, during a symposium (i.e. a drinking party), a finely decorated hydria would have been used to pour water into a krater in order to dilute wine.

There are a number of ancient Greek – mostly Attic – vases that depict women filling hydriai at a fountain house. Fountain houses like those shown in the vase-paintings have been attested archaeologically, e.g. in Athens. The vase-paintings often depict the women balancing the vessels on the tops of their heads to make them easier to carry. Such scenes give us an invaluable glimpse into everyday life in ancient Greece.

Further reading

- John Boardman, The History of Greek Vases (2001).

- Andrew J. Clark, Maya Elston, and Mary Louise Hart, Understanding Greek Vases: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques (2002).

- Robin Osborne, Archaic and Classical Greek Art (1998).