Recently, I picked up a copy of Philip Hardie’s The Last Trojan Hero: A Cultural History of Virgil’s Aeneid. I’ll be writing a review of that eventually, but the cover featured artwork based on a fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

Tiepolo was a famous Italian painter who lived from 1696 to 1770. Two of his sons would later help him out and become painters in their own right, working in a very similar style. Their work has helped shape, for better or for worse (I’d like to think for better!), how we visualize the ancient world.

Influential works of art

Tiepolo created works that dealt with a wide variety of topics, but in this article I want to showcase some of the paintings he produced that took their inspiration from Classical mythology. Artwork like this has exerted a great influence that is felt to this day: when Hollywood looks for inspiration for their movies set in the ancient world, they take their cues to a large degree from painters of the Renaissance and later, including artists like Tiepolo.

Of course, back in the eighteenth century, people didn’t know as much about the ancient world as they do today. Artists like Tiepolo based their work on ancient written sources (or summaries of them), and kitted out ancient figures in contemporary dress or, at best, in clothing inspired by ancient statuary. It’s worthwhile to point out that the eigtheenth century witnessed the first excavations at Pompeii, with research conducted by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) exerting a large influence on the neoclassical movement.

Since the works of artists of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries are now all firmly in the public domain, they are often reproduced in books that deal with the ancient world, including Latin and ancient Greek textbooks, popular magazines, and so on. Use of such pictures is cheap (essentially free!) and besides, they look great.

However, keep in mind that these are simply works inspired by the ancient world and not intended to be historically accurate. Note, for example, the lack of colour on the ancient statues in the paintings below.

Gallery

Apollo Pursuing Daphne

This painting is based on a story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which itself was inspired by Greek myths. In Ovid’s version of the tale, the god Apollo had become infatuated with a nymph called Daphne. He pursued her relentlessly, leading Daphne to pray to her father, the river god Peneus, to help her. She is then transformed into a laurel (called daphne in Greek). Oil on canvas; ca. 1755–1760. National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.).

Bacchus and Ariadne

Arianda was the daughter of King Minos of Crete. She had fallen in love with the hero Theseus and decided to help him defeat the Minotaur by giving him a call of yarn that he could use to keep track of where he was inside the labyrinth that served as the monster’s prison. After slaying the creature, Theseus and Ariadna fled. They camped out on the island of Naxos, where the god Dionysus (also known as Bacchus) appeared to Theseus in a dream and told him to abandon the Cretan princess. This he did, leaving Ariadne devestated when she woke up next morning only to find Theseus gone. But soon Bacchus arrived and made Ariadne his wife and a goddess in her own right. Oil on canvas; ca. 1743-1745. National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.).

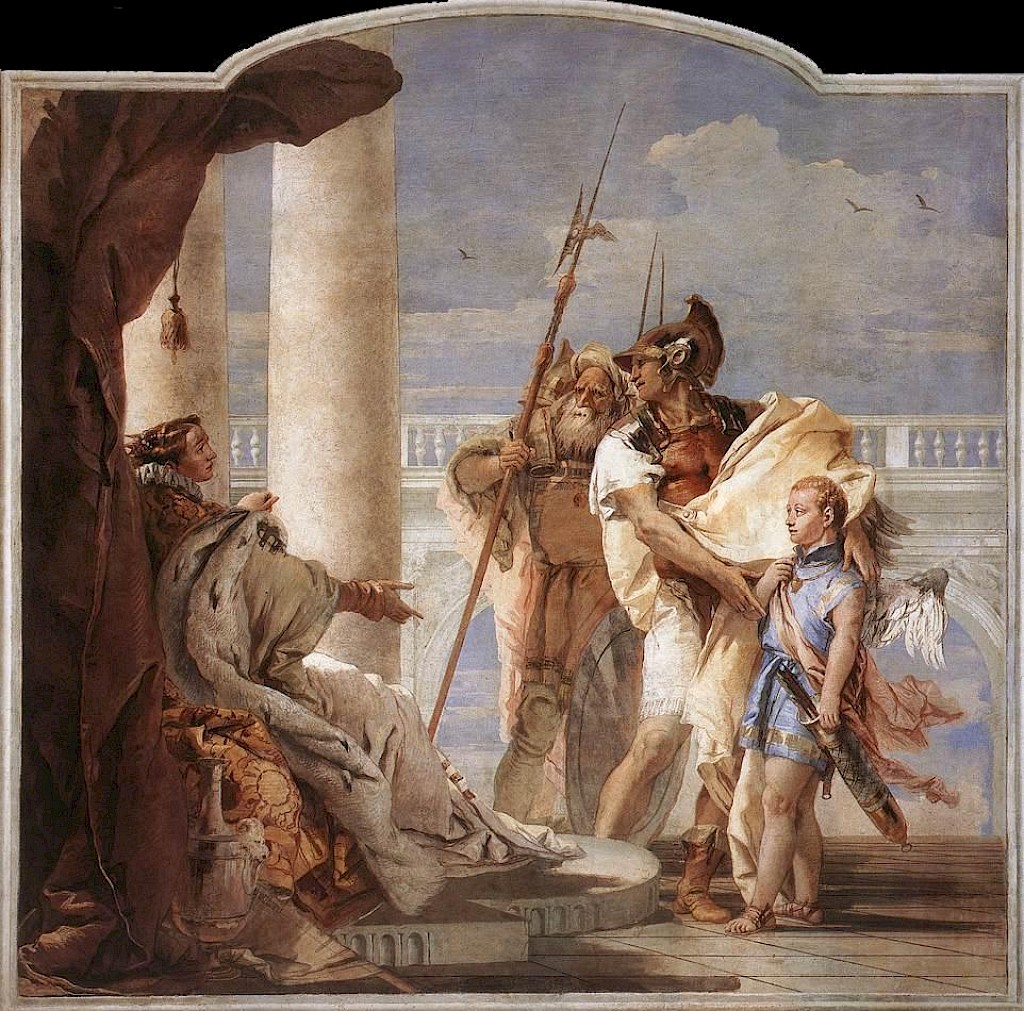

Aeneas Introducing Cupid Dressed as Ascanius to Dido

On his way to Italy, the Trojan hero Aeneas stops at Carthage. Juno, Jupiter’s wife, doesn’t want Aeneas and the Trojans to reach their destination and convinces Venus, the goddes of love and Aeneas’ mother, to swap Aeneas’ son Ascanius with Amor in disguise. Amor (Cupid) will ensure that Aeneas and the Carthaginian queen Dido will fall in love. In the painting, you can see that Ascanius is equipped with a bow and arrows: the symbols of Amor (Cupid). He also has wings, another reference to Cupid. Fresco; ca. 1757. Villa Valmarana ai Nani (Vicenza, Italy).

The Death of Dido

Aeneas and Dido have fallen in love, but Aeneas has to leave to continue his search for a new Trojan homeland. When Dido sees him and his fleet leave Carthage, she ascends a pyre and kills herself using a sword that Aeneas had given her, but not before cursing the Trojans and proclaiming an endless fued between Carthage and the descendants of the Trojans (i.e. the later Romans, thus providing an explanation for the Punic Wars). Oil on canvas; ca. 1757-1770. Pushkin Museum.

The Rape of the Sabine Women

Romulus founded the city of Rome. His followers consisted solely of men, which meant that the city was essentially doomed. In order to ensure the continued survival of the Roman race, the men decided to abduct women from the settlements near Rome. The people who lived nearby were called the Sabines. Oil on canvas; ca. 1718−1719. Sinebrychoff Art Museum (Helsinki, Finland).