The appeal of Carthaginian military institutions is easy to understand: Carthage was Rome’s most tenacious enemy on its rise to Mediterranean dominance, but no Punic historical texts exist. Even the Greek and Roman sources that do survive are frustratingly incomplete.

While these issues add a mystique to most things Punic, they also mean that studying Carthaginian warfare is difficult. The absence of detailed literary evidence and the attraction to the subject has led to some historically dubious ideas or even outright fabrications being spread as fact.

The ancient sources

What we know of the Sacred Band of Carthage comes from three passages concerning two events. Two of these are found in Diodorus Siculus, the writer of a massive “universal history” in the first century BC, and one is found in Plutarch’s biography of Timoleon, written in the early second century AD.

The first time we hear of this unit is in the narratives of the Battle of the Crimisus (339 BC), a fourth-century engagement between a large Carthaginian army and the Corinthian condottiero, Timoleon. The allied-Greek army ambushed the Punic force as it was crossing the River Crimisus (Sicily), and fought a long struggle, in pouring rain, until the latter broke.

In his description of the battle’s aftermath, Diodorus wrote that “in the end, even the Carthaginians who composed the Sacred Band, twenty-five hundred in number and drawn from the ranks of those citizens who were distinguished for valour and reputation as well as for wealth, were all cut down after a gallant struggle” (Diod. Sic. 16.80.4). This is all he says of them directly.

In Plutarch’s version of events there is no actual mention of the Sacred Band. He does note that 10,000 infantrymen were seen bearing white shields, wearing splendiferous armour, and marching in a well-regulated manner. These the Greeks “conjectured to be the Carthaginians” because of their equipment and their professional march (Plut. Tim. 27.4-5).

We may find the Sacred Band listed in the casualty figures presented by Plutarch, when he relates that amongst the dead “three thousand were those of Carthaginians, a great affliction for the city. For no others were superior to these in birth or wealth or reputation” (Plut. Tim. 28.10-11). Although the number does not match-up with Diodorus’ 2,500, they are close enough that it is safe to assume the dead mentioned by Plutarch were members of the Sacred Band.

This is all we hear of the Sacred Band at the Battle of the Crimisus. The soldiers that were enrolled in it were clearly from the wealthy families of Carthage, wore ornate armour, and fought and acted like a professional fighting-force. Beyond this, we can’t say anything.

The next time that we hear of the Sacred Band is at the Battle of White Tunis (310 BC), which took place in North Africa between the Carthaginians and the invading army of Agathocles, tyrant of Syracuse. The latter had invaded Libya in a daring gambit to relieve Sicily and Syracuse in the face of a major Punic invasion.

Agathocles had moved his army close to the city of Carthage, near a settlement known as White Tunis in our sources (presumably somewhere near modern Tunis). The Punic leadership appointed two generals, Hanno and Bomilcar, who led a sizable army out to confront the invaders.

When they arrayed for battle, each general took command of a wing of the Carthaginian army. On the right-wing was Hanno, under whose command was the Sacred Band (Diod. Sic. 20.10.6). Seeing this, Agathocles stationed himself on the Greek left-wing (opposing Hanno) along with his 1,000-strong bodyguard of hoplites (Diod. Sic. 20.11.1). We can infer from this that there was some way for the Greeks to recognize the members of the Sacred Band. Perhaps it was their white shields, as they may have carried at the Crimisus, or maybe it was their spectacular armour?

Diodorus goes on to write that the Sacred Band fought valiantly against their opponents and continued to fight even after Hanno was killed in combat (20.12.3-4). They continued even after the rest of the army began withdrawing towards Carthage (Diod. Sic. 20.12.7).

This is all we hear of the Sacred Band in this battle and is the last time that they appear in any of our sources. They are absent from the wars between Carthage and Rome and are not to be found in Polybius’ narrative of the Truceless War.

The extent of our knowledge

So, what do we really know about the Sacred Band?

We know that they were Carthaginian citizens and that they were renowned for both their valour and their wealth. They seem to have marched and fought at a professional level. They also wore ornate armour, perhaps meaning made of precious metals or decorated with them.

Plutarch’s note that the Carthaginian citizens at the Crimisus carried white shields may mean that these were carried by the Sacred Band, but they are ascribed to a citizen-force of 10,000 soldiers.

Now that we have seen what limited information our sources provide us, let’s look at some of the things said about them in a couple of pieces of online-content.

Misinformation online

The main inspiration for this article was a YouTube video created by a user who calls himself “Ancient History Guy”. His YouTube channel is dedicated to creating short, well-animated videos that look at different aspects of ancient warfare. While I enjoy the style of these, this particular video raised too many red-flags with me to remain quiet.

Here is a play-by-play of the nine most striking “facts” presented in this particular clip:

- The Sacred Band was a unit of infantrymen which fought in Carthaginian armies during the fourth century BC.

- This was a “very unusual unit, as Carthaginian citizens usually only served as officers or cavalry in the armed forces.”

- It consisted of between 2,000 and 3,000 men.

- “Trained from an early age to be tough phalanx spearmen, these men were from wealthy Carthaginian families.”

- “As a result of bordering a Greek city-state in Sicily, many of the weapons and armour used by the Sacred Band were copies of Greek armour and weapons.”

- “This included the linothorax (…) the Sacred Band would often have symbols of Tanit, who was the patron goddess of the unit, painted onto the armour.”

- “The most popular type of helmet worn by the Sacred Band was the Thracian helmet, this helmet was again often painted.”

- “In terms of weaponry, the Sacred Band often used the Greek hoplite shield (…) often the Carthaginians preferred the xiphos sword, however their primary weapon was a thrusting spear.”

- “With its destruction in 310 BC, the Sacred Band disappeared from historical records.”

I have not listed here a few more basic pieces of information provided in the video. Primed with the discussion of the first section of this article, most readers will probably question a number of assertions made in Ancient History Guy’s clip: their doubts are warranted.

The first statement in the list above is astute: the creator acknowledges that we only hear of the Sacred Band in the fourth century BC. He does not try to extrapolate its existence to other periods of Punic history, which would be problematic.

The second point, that the Sacred Band was a “very unusual unit” as Punic citizens typically served only as officers or cavalry, is not well-founded in a thorough reading of the sources. This is, instead, based in the historically dubious conclusion of some modern historians that the Carthaginians relied almost entirely on mercenaries. However, we hear of citizen-units frequently, and it was really only with the First and Second Punic Wars that they essentially disappear from campaigns outside of Africa. In other words, the creator is here promulgating a problematic topos.

The third fact presented is that the Sacred Band consisted of between 2,000 and 3,000 soldiers. This is not entirely wrong, although the “2,000” has seemingly been created ex nihilo, as we hear from Diodorus that it consisted of 2,500 men, whilst Plutarch can be read to imply their strength was 3,000. Unfortunately, Diodorus does not give us a figure for the unit’s strength at the Battle of White Tunis. Agathocles only seems to have needed 1,000 hoplites to oppose them, though, so that could have been closer to the Sacred Band’s strength at this engagement.

The fourth point is half true, half conjecture (at best). It is true that our sources say they came from wealthy Carthaginian families, but we hear absolutely nothing about them training from a young age. Perhaps the creator is here getting the Sacred Band confused with the Spartans.

In Diodorus’ description of the unit at the Crimisus, he says that it consisted of soldiers “drawn from the ranks of those citizens who were distinguished for valour and reputation, as well as for wealth” (Diod. Sic. 16.80.4). This could be read to mean that they were veterans who were “recruited” into the Sacred Band for their conduct in previous battles or campaigns. Again, at White Tunis, Diodorus says that the Sacred Band consisted of “picked men” (epilektoi andres; Diod. Sic. 20.12.3). Thus, our sources make it sound as though the Sacred Band was either an ad hoc unit, formed on campaign from distinguished veterans, or at most formed in advance of a campaign. These notices, though, almost certainly rule out the possibility that the unit trained together from youth.

The fifth point, that by bordering a Greek city-state in Sicily, the Sacred Band (or Carthage more generally) was encouraged to copy Hellenic arms and armour is sensible, although perhaps a misinterpretation of the evidence. From iconographic evidence, it appears that Punic and Phoenician troops had adopted the Greek “hoplite kit” earlier than Carthaginian involvement in Sicilian affairs began. For example, the Amathus Bowl, dated to ca. 700 BC, features warriors with closed helmets and Argive shields and spears. (It would be wrong to condemn Ancient History Guy for this particular comment, though the way it is presented in the video undercuts what is actually a longer and very interesting, history of arms development in the Iron Age Mediterranean.)

The sixth point is problematic. The assertion that the Sacred Band preferred the linothorax is logical, as this was probably the most popular type of armour throughout the Mediterranean in the fourth century BC. But, there is nothing in our sources which ascribes it to the Sacred Band. Plutarch actually notes, during the Battle of the Crimisus, that the Carthaginians wore “iron breastplates” that, combined with their large shields, made them very hard to kill (Plut. Tim. 28.1). Thus, it is problematic to say in a matter-of-fact way that the Sacred Band preferred the linothorax.

What is worse about the sixth point, however, is that Ancient History Guy claims that the unit painted their armour with symbols of Tanit, their supposed patron deity. There is zero evidence for this practice. While Tanit was an important goddess for Carthage, other martial deities were also prominent, notably Melqart, who is often described as a Phoenician parallel for Heracles.

Even then, we aren’t given reason to think that the Sacred Band was connected to any specific deity, or to the gods at all. The name of the unit as we know it comes from a Greek source and may not reflect the true nature of it. We are forced to acknowledge that we don’t know anything about its divine connections, or absence thereof.

The seventh point, that the Sacred Band preferred the Thracian helmet, poses a similar problem. This type of helmet was very popular across the Mediterranean in the fourth century BC, but there is no actual evidence for its use by the Sacred Band.

The eighth point is problematic for the same reason. It is probable that the Sacred Band fought with both a “hoplite shield” (large, round, and hollow) and a long thrusting spear, whilst carrying a short-sword as a backup for the spear. This aligns almost exactly with the arms and armour carried by many Mediterranean armies of the time. But, again, our sources do not provide much detail with regards to the unit’s armament.

Plutarch does mention “spear thrusts” during the Battle of the Crimisus, and notes that the struggle eventually “came to swords” (Plut. Tim. 28.1-2). But he does not speak directly about the Sacred Band; and it is worth noting that the “spear thrusts” here are evidently being delivered by the Greeks. Thus, again the creator felt the need to fill the vacuum.

The ninth point is minor, but worth noting. In the video, Ancient History Guy says that “with its destruction in 310” we never again hear of the Sacred Band. It is true that they are not seen again in our sources after 310 BC, but it is not true that the unit was destroyed in the battle. Diodorus tells us that they fought on valiantly, but eventually withdrew when the rest of the army had left the field (Diod. Sic. 20.12.7).

Thus, our only source on for the battle explicitly states that the unit was not destroyed. It is possible (if not probable) that it was disbanded afterwards, but that is a much different thing than being wiped out in battle.

Conclusions

Sadly, the video produced by Ancient History Guy offers a distored image of the Carthaginian Saced Band.

I was curious as to where Ancient History Guy found some of the information that he presents as fact in his video. My first recourse was to his brief bibliography, which can be found at the end of the clip. All three of these are from Ancient History Encyclopedia, a major digital project, with content that is generally acceptable. Having read the three articles, I found that none of them were the source of the erroneous information. I was perplexed.

I then went in search of where the content-creator found this stuff. A quick Google search led me to this dubious website. It appears that Ancient History Guy found much of his counter-factual additions there. My research into this issue was thusly concluded.

My purpose in writing this article, though, is twofold. The first is to make sure that viewers of this video are provided with the opportunity to see what we actually know about the Sacred Band and not be taken in by some of the falsehoods they may find online.

My second point, however, is to point to a problem with online-content that reaches beyond this video and the website I’ve just noted. They are not always the same as a scholarly-article or book. While academic historians look to primary sources for their reconstructions of the ancient world, not all creators online do this. In the case of this video on the Sacred Band by Ancient History Guy, he only consulted three articles from a generally reliable place and, probably, a fourth from a very dubious website. Had he gone straight to Diodorus and Plutarch, I am sure that he would not have promulgated as many of the fabrications that he did.

Online creators need to realize that when they are presenting things as facts, whether historical or related to modern issues, they have a duty of due diligence to their audience and should ensure that what they are presenting as absolute truths are backed up with evidence and verifiable.

It is, of course, good for enthusiasts to present theories about historical topics in their content, but it should be signposted as such. In academic literature we often take for granted that opinion is presented as opinion, and fact is presented as fact, but this comes, in part, from years of university-level training. By not performing due diligence, content creators are contributing to the spread of misinformation online, which is similar to the current plague of “fake news” that is now so ingrained into our news cycle.

Some people may not see the problem with this as the ancient world does not have the same impact as modern social and political issues. The use of ancient narratives, or misinterpreted narratives, by white supremacists, and others, though, is evidence of why it matters to continually seek out the truth. For these serious misuses of antiquity, the field has spawned organizations like Pharos.

The problem of online misinformation cannot be ignored, but a solution is not easily devised. I hope that the readers of this article will see, however, that even the slickest looking online-content must be consumed with a healthy amount of scepticism. I also hope that any content-creators who read this will take to heart my plea for them to acknowledge the duty that they have to their audience in creating well-researched pieces.

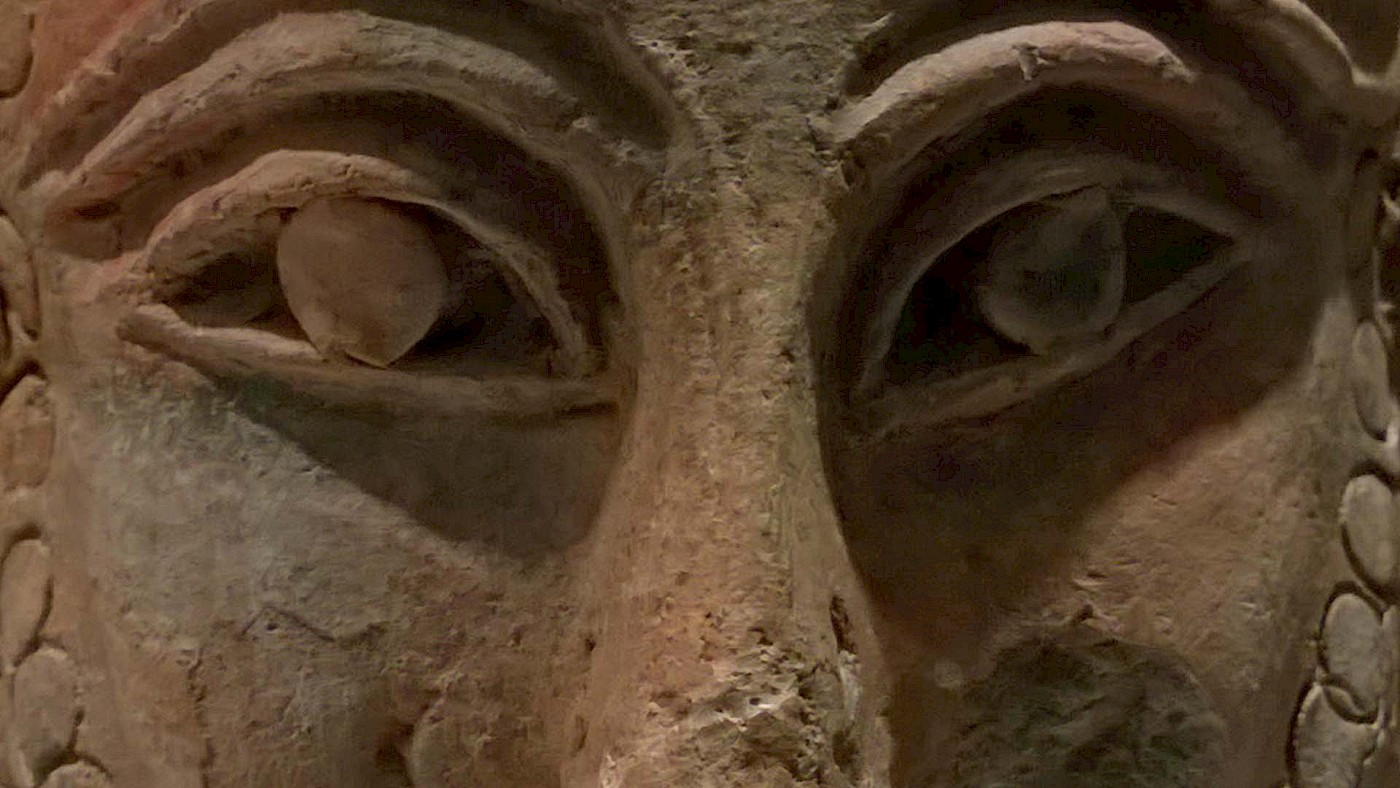

This article’s featured image is a close-up of a terracotta mask of a bearded man from Carthage. Dated to the early fifth century BC. Currently in the Musée national du Bardo (inv. no. B2; tt 147). Photo taken in 2015 at an exhibition on Carthage in the National Antiquities Museum, Leiden.