Prinias is a village located in the centre of Crete, about 35 km southwest of the island’s capital city of Iraklion, and about 20 km from Knossos. Nearby is an important archaeological site (ancient Rhizenia or Rhettenia) where the remains of two temples have been unearthed, Temple A and the earlier Temple B. My focus here is on Temple A, which is, in the words of L. Vance Watrous, “the earliest building decorated with sculpture known in the Greek world” (1998, p. 75).

Temple A was excavated in the early years of the twentieth century. It has been dated to the second half of the seventh century BC. Excavations have revealed that the temple was founded on the spot where cult activities took place from the Late Minoan IIIC period (ca. the twelfth century BC) onwards (Mazarakis Ainian 1997, p. 336), so the site was considered sacred centuries before this temple was even built. The remains of the structure occupy a spot on the ridge known as Patela, which was also the site of the ancient town. Nearby is a rich cemetery dating from the Late Minoan IIIC to Archaic periods.

The ground plan of Temple A is rectangular. But there is considerable disagreement about what the building originally looked like. The original excavator, L. Pernier, believed that the temple had a flat roof, and this seems likely to have been the case. A reconstruction with a pitched roof is found in, for example, Richard Neer’s book on Greek art and archaeology (i.e. fig. 119 on p. 119), but there is little evidence in support of this interpretation. Roof tiles, for example, are lacking, as are the supports for the top of the roof.

The sculptural elements from Prinias are currently all on display at the archaeological museum of Iraklion. Some of the reliefs are fragmentary; Watrous, for example, restores pieces of which only the lower legs have survived as sphinxes in his proposed reconstruction of Temple A (1998, p. 77 fig. 8.1). The fact that these legs have hooves would, however, suggest that these were not originally sphinxes.

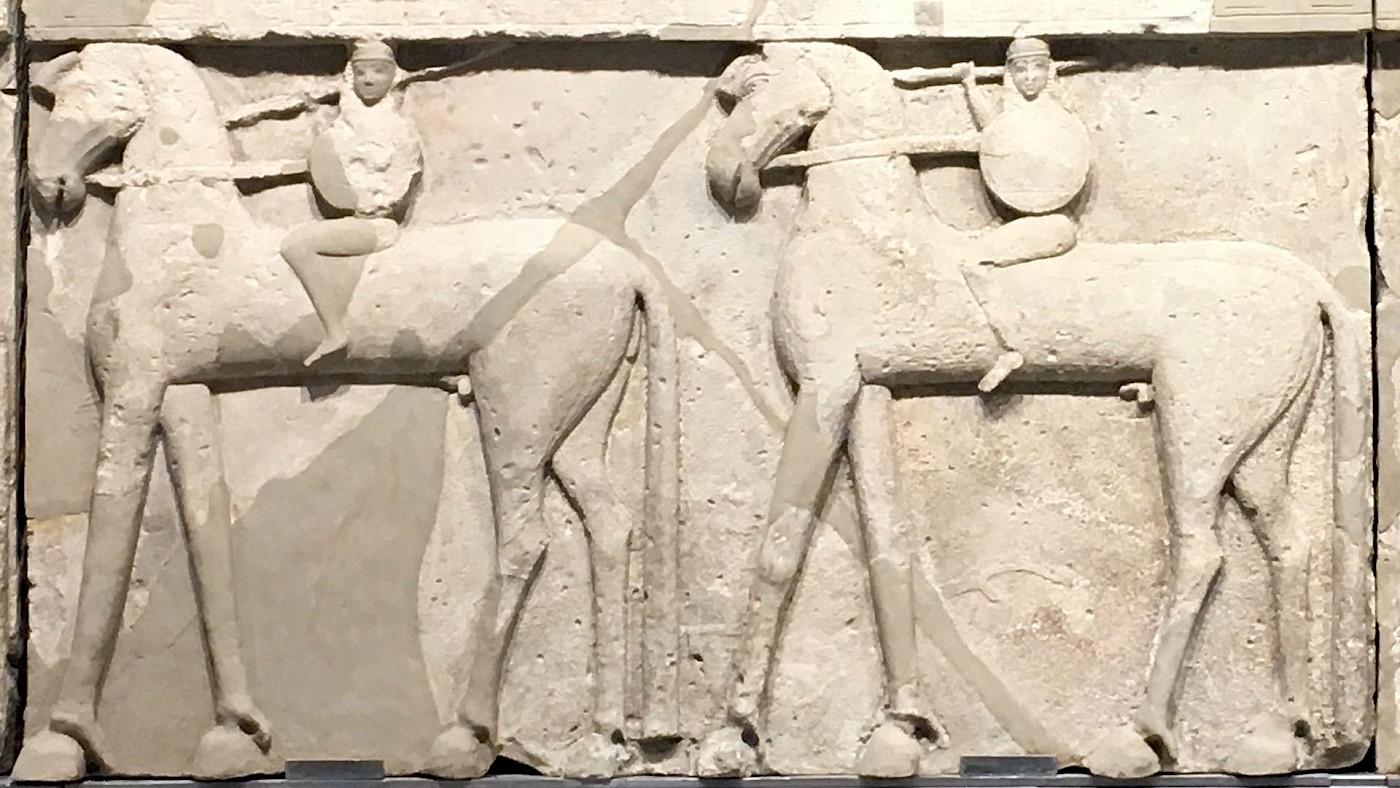

A relief featuring horsemen

Scholarly debate has mostly focused on where the sculptural elements of the temple were originally located. Watrous is surely correct in asserting that the largest relief, consisting of a number of stone slabs featuring armed horsemen, had originally been located high up, probably directly underneath the edge of the roof. The panels of this relief, two of which are depicted in this article’s featured image, are thin, and were used as decoration. As Watrous points out (1998, pp. 76-77):

In addition, the long-legged proportions of the horses are not necessarily a sign of an early seventh century date […], but are best understood as a deliberate attempt to compensate for the visual foreshortening that their placement high on the temple façade would create.

These horsemen are interesting. They each have a large round shield. This must almost certainly be an Argive type shield, the hollow shield with a double grip that is commonly associated with the ancient Greek hoplite. This shield has a central band through which the left arm is thrust and another grip near the edge for the left hand. The reigns of the horses are clearly held by this same left hand, as these warriors each brandish a spear in their right.

These armed riders are almost certainly a form of mounted infantry. I’ve written about them in more detail in my PhD thesis: a very brief description can be found in an article I wrote about the “Horseman of Grumentum”. There’s also a link there to download a peer-reviewed article I wrote about the subject. Briefly, my idea is that the Argive shield, so commonly associated with the hoplite, was specifically invented to be used by men who spent a gerat deal of time on horseback, and who even rode into battle.

Images of these armed horsemen are found throughout the Greek world of the Archaic period, i.e. roughly the seventh and sixth centuries BC. A Corinthian aryballos of the sixth century BC, described in the aforementioned article, labels one such figure as an hippobatas or “horse-fighter”. These figures are found in Greek art everywhere from the Peloponnese and Central Greece to the Aegean islands and Anatolia, as well as in Southern Italy and, as demonstrated by this relief from Prinias, also in Crete.

Further reading

- W.G. Cavanagh, M. Curtis, J.N. Coldstream, and A.W. Johnston (eds), Post-Minoan Crete: Proceedings of the First Colloquium (1998).

- A. Mazarakis Ainian, From Rulers’ Dwellings to Temples: Architecture, Religion and Society in Early Iron Age Greece, 1100-700 BC (1997).

- R.T. Neer, Art & Archaeology of the Greek World (second edition, 2012).

- L.V. Watrous, “Crete and Egypt in the seventh century BC: Temple A at Prinias”, in: Cavanagh et al. (1998), pp. 75-79.

- J. Whitley, The Archaeology of Ancient Greece (2001).