Excavations at the seaside town of Lefkandi began in the summer of 1964. Archaeologists Mervyn Popham and Hugh Sackett led a team from the British School at Athens to excavate the Xeropolis tell that juts out from the island of Euboea into the gulf separating it from Attica and Boeotia. These excavations revealed a settlement, particularly prosperous in the late eighth and twelfth centuries BCE, but – in these initial excavations – little evidence between those centuries in the so-called Greek Dark Age.

In the summer of 1968, graves contemporary with the apparent lacuna on Xeropolis were discovered on the hillside opposite the site. The British excavators were asked to assist P.G. Themelis of the Greek Archaeological Service with investigating this apparent cemetery. During the second summer of excavation, they turned to the site known as Toumba, believed to be the place of settlement at Lefkandi in the eleventh through ninth centuries.

Investigation revealed another cemetery that was not just another cemetery. Over the next few decades, excavations at Toumba would go on to reveal more than eighty graves containing gold, faience – glazed ceramic beads – and connections to the eastern Mediterranean far stronger than any known in the Early Iron Age Aegean world before the cemetery was excavated. In 1980, they would discover the famous monumental building containing the most spectacular burials of a cremated man and a woman clothed with gold, but even before then the Lefkandi-Toumba cemetery had revealed that the Dark Age deserved more attention.

At the bottom of the first grave excavated a ceramic head, broken at the neck, was discovered. Several days later, on the cover slab of another tomb, the body that connected to this head was found. The completed figurine had the upper body of a man and the lower body of a horse: a centaur.

The first of these tombs, Toumba Tomb 1, was dated by Vincent Desborough to 900-875 BCE, the early Sub-Protogeometric I pottery phase, while the tomb in which the body was discovered, Toumba Tomb 3, was slightly earlier: 925-900 BCE, Late Protogeometric. The Centaur’s body was also decorated in the Protogeometric style. In a period in which mythological depictions were unknown, such a clear representation was startling to see.

A closer look

Restored, the Lefkandi Centaur stands 36 centimetres tall and 26 centimetres long. It is still missing the end of its tail and most of its left arm, which once held something, perhaps a branch like those held by centaurs in later depictions, over its shoulder where there is another clear break. Decoration covers its body from the top of its head to the missing tail, with the exception of the underbelly of its horse parts.

The human body and four legs are made of solid clay. The horse body is a hollow cylinder, as indicated by the holes at the front and on the back. This body was thrown on a wheel, and resembles a contemporary Attic Stag Figurine from the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens.

Unlike some other “early” depictions of centaurs from the eighth century BCE in Greece, the Lefkandi Centaur has four horse legs, the front two with knobbly knees. On the front-left leg there is a deep incision, seemingly intentionally made before firing. This incision seems intended to represent a leg wound, and is one of the first indications that this figurine represents a specific centaur.

The next feature is the surviving hand, which rests on his right hip. Five incisions on this hand indicate that he has six fingers. In case this appears to be a mistake, it is worth noting that the fingers are represented in paint as well as modelling, with thick dots to indicate knuckles.

The final element is perhaps the least convincing, at least on its own terms. Unlike later centaurs, the Lefkandi figurine has no genitals either on its horse or human body. While the limited contemporary artistic repertoire means that we do not know if the creator was likely to have depicted a centaur with genitals, the decoration of its body may indicate that the Lefkandi centaur is intended to be understood as being clothed (Desborough et al. 1970, p. 25).

Centaur identification

In later Greek mythology, centaurs are often portrayed as a group, as in the battle between Lapiths and centaurs at the wedding of Peirithous. But some centaurs stand out as individuals. Most notable among these is Chiron, the centaur who lived on Mount Pelion in southern Thessaly where he trained numerous heroes, including Achilles and Herakles.

The Lefkandi Centaur has been identified as Chiron since the original publication of the cemeteries (Lefkandi I, p. 449, n. 450). Initially, this was based on his wounded knee, as according to Pseudo-Apollodorus this is where Herakles shot his former teacher with poisoned arrows, leading to Chiron’s death (Bibliotheca II.v.4). For while the centaur was immortal, the pain he felt led him to give up his immortality and die.

In Greek mythology, immortality simply means that one cannot die, hence the story of Eos/Dawn and Tithonius. When Eos asked Zeus that her human lover Tithonius be made immortal so that they could be together forever, Zeus neglected to also grant him eternal youth so he simply continued to grow old (Hom.Hymn 5, 218-38). Even gods can be wounded and must be healed with medicine. In Chiron’s case, he was undying, but the wound could not be healed so he chose to die.

In addition to the wound, the Lefkandi Centaur’s polydactylism has also been associated with Chiron. Here, the connection is weaker – a general association of additional fingers with wisdom, rather than a specific, albeit much later, example of a myth (Lefkandi I, p. 449, n. 450).

The identification of Chiron as a wise healer goes back as early as is possible in Greek myth. Chiron is referenced twice in the Iliad, in both cases for his healing abilities (Il. 4.217-219; 11.828-832). In the latter case, his role as Achilles’ teacher is also referenced.

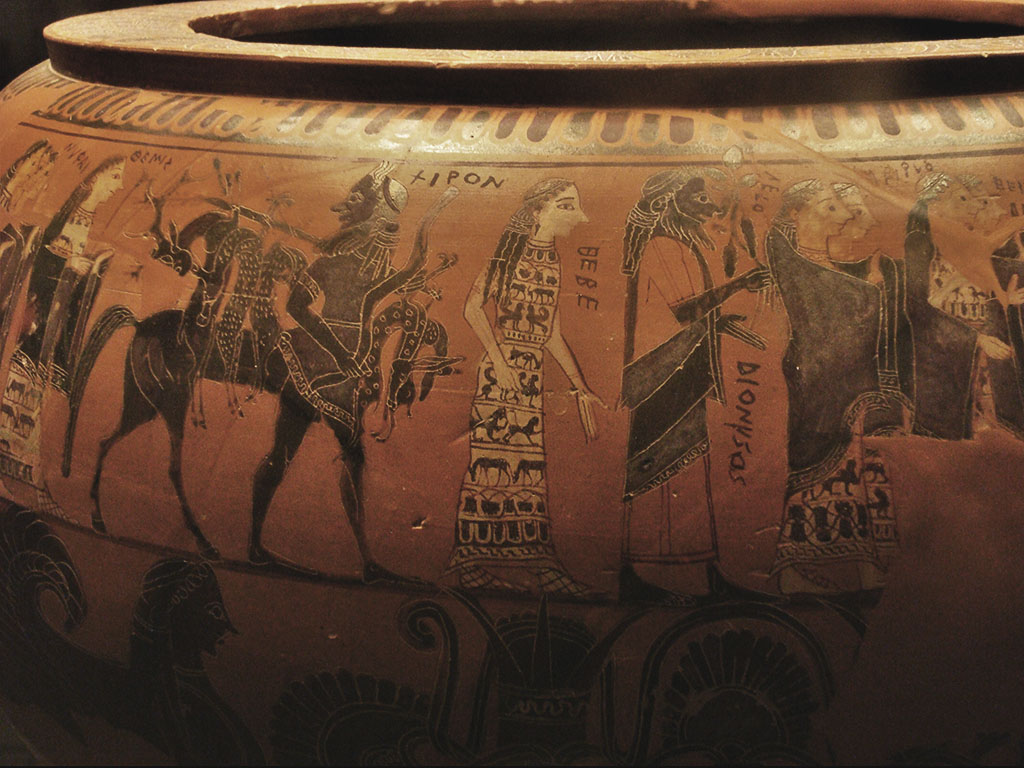

The possibility that the Lefkandi Centaur was clothed may in fact be the strongest evidence that this figure is intended to be Chiron. In the sixth century BCE, when Greek vase painters label their characters as well as indicating who they are through attributes, Chiron is often depicted wearing clothing, in contrast to other centaurs who are usually naked. As human/animal hybrids, centaurs occupied a space between the natural world and the human, hence the branches they carry and their association with hunting and perhaps even childhood. Chiron, clothed, is closer to human, but still somewhat apart. It is possible that earlier depictions, such as the centaur on a ceramic shield from Tiryns in the Argolid that is also clothed and carrying a brace of rabbits, are also Chiron (Langdon 2008, pp. 70-71).

Counter to this identification is the simple fact that we have no sources for myths as the Greeks of the tenth and ninth century understood them. We do not know if they knew of Chiron, his pedagogical role, his wound, his wisdom. Even if we were sure that the Lefkandi Centaur were Chiron, is there any way that we can understand the meaning connected to this mythological figure in a time without writing?

Centauromachy

In order for our understanding of the Lefkandi Centaur to progress, we must understand its context: the Toumba Cemetery at Lefkandi, the head at the bottom of Tomb 1, the body on the cover of tomb 3. This figurine had been intentionally broken and intentionally placed in two separate burials.

The intentional destruction of objects is not uncommon in Early Iron Age burial. Arguably, the rise of cremation in this period is an intentional act of destruction targeted at the very bodies of individuals; more securely, swords and perhaps even the monumental building in the Toumba cemetery were all destroyed as part of funerary rituals.

But there are no other examples of which I know where one object was broken in two and placed in two different burials. What was significant about these burials?

Both tombs are shaft graves: a compartment cut into the ground and covered with stone slabs. Tomb 1 is 140 cm by 90 cm, while Tomb 3 is 200 cm by 115 cm, suggesting that the latter grave was for a larger person than the former.

At one end of the Tomb 1 were found a handmade bowl, a handmade dipper, an oinochoe (wine jug), and the Centaur’s head. At the other end, a juglet or small lekythos was found. Clustered in the middle of the grave were a pair of gold earrings, two small bronze bracelets, two bronze arched fibulae, and a necklace of glass and faience.

Most of the finds in Tomb 3 were found on the covering slabs, which had collapsed into the grave. These include five lekythoi (oil jugs), a seashell, an animal figurine in poor shape, perhaps a donkey, and the body of the Centaur. Inside the grave were two gold “attachments”, thin necktie-shaped decorations, a bronze fibula, and an iron knife with a curved blade and ivory handle.

Neither grave contained a significant amount of bone that would allow anthropological identification of the person buried. Thus, we rely on the size of the tombs and the finds inside them to identify the occupants.

The excavators did not offer a consistent answer to the question of the gender or age of those buried in these tombs. At one point, Tomb 3 is identified as that of a man (Lefkandi I, p. 204), but not consistently (Lefkandi I, p. 420). Both contain miniature vessels, which usually indicates a child burial, and the small size of the bracelets might be another indication that the deceased in Tomb 1 was young, but the other finds do not typically support such a straightforward explanation, particularly the knife (Lefkandi I, p. 205). The suggestion that the Centaur was a toy was also raised, although it would be a fairly spectacular toy (Desborough et al. 1970, p. 27).

This knife in Tomb 3 was identified as unusual, perhaps with ritual significance. The excavators also wondered if the animal figurine and Centaur might be rhyta – ritual pouring vessels – but they did not suggest a unified explanation for these features.

It should also be noted that there is nothing much unusual about any of the other finds in these graves. All of the cemeteries at Lefkandi revealed gold and bronze jewellery, but the Toumba was always the richest, even before the discovery of the burials in the monumental apsidal building that appears to have initiated the cemetery. The decapitated Centaur split between them is the most unusual feature of these graves.

Finding meaning

In his discussion of the Centaur in the first publication of the Lefkandi cemeteries, P.G. Themelis imagines the head of the figurine being severed from its neck in a violent chthonic ritual by the graveside, perhaps connected to the then-unexcavated tumulus under which the monumental apsidal building would be excavated a few years later (Lefkandi I, p. 216).

This explanation offers no insight into why a centaur is the object of this otherwise unparalleled cultic act. The identification of the Centaur as Chiron does offer an insight here. As Chiron, the Centaur links together the concept of a heroic childhood as the teacher of heroes, the healing arts with which he is specifically connected, and the tragedy of his death, poisoned by his pupil Herakles and forced to sacrifice his immortality to end his suffering.

Susan Langdon offers the speculation that the relationship between the two graves may be pedagogic. The occupant of Tomb 3, with their knife and rhyton, may have been a special individual, perhaps a healer like Chiron, while the smaller individual in Tomb 1 may have been their young apprentice (Langdon 2008, pp. 71-74). On the basis of the jewellery, Langdon believed the individual in Tomb 1 might have been a girl, connected to Chiron because of the symbolism of healing.

How deeply we can connect the myths of Chiron to the lives and deaths of the individuals buried in Toumba Tombs 1 and 3 is debatable, even if the figurine is correctly identified as Chiron. It is fair to say that, without parallel circumstances, claiming any certainty in this interpretation is inadvisable. Yet claiming that we are completely ignorant of the meaning behind this act is defeatist, and ignores the many elements connected to the Lefkandi Centaur that can be connected to meanings that we do understand.

There are, however, wider consequences to accepting that the Lefkandi Centaur represents Chiron. If this is Chiron, we have identified him on the basis of two of his defining features as a Centaur in later history: his wisdom, and his wound. The presence of these features in a tenth-century depiction suggest a deep history to these myths that would seem to persist unchanged for many centuries.

The meagre surviving iconographic evidence from the Early Iron Age limits our understanding of the development of Greek myths at this time, but the Lefkandi Centaur, as a snapshot, suggests that there was a rich mythological repertoire underlying the period, probably expressed through storytelling rather than art.

Further reading

- V.R. Desborough, R.V. Nicholls, and Mervyn Popham, “A Euboean Centaur,” The Annual of the British School at Athens 65 (1970), pp. 21-30.

- Susan Langdon, Art and Identity in Dark Age Greece, 1100-700 BCE (2008).

- A. Lebassi, “The Relations of Crete and Euboea in the Tenth and Ninth Centuries B.C.: The Lefkandi Centaur and his Predecessors”, in: D. Evely, I. S. Lemos, and S. Sherratt (eds), Minotaur and Centaur: Studies in the Archaeology of Crete and Euboea Presented to Mervyn Popham (1996), pp. 146-154.

- M.R. Popham, L.H. Sackett, and P.G. Themelis (eds), Lefkandi I: The Iron Age (Text) (1980).