While some remains of the ancient world can still be seen above ground, like the Temple of Minerva at Assisi, most have been swallowed up by the earth over the course of time as the result of wind and rain, floods, and later building activities. In some cases, the underground remains are in such a good state of preservation, that they can be turned into attractive places to visit, like the Roman covered marketplace underneath San Lorzeno Maggiore in Naples.

Located partially underneath the town hall of Spoleto, in Umbria, are the remains of a richly decorated Roman house. Based on a stylistic analysis of the house’s mosaic floors, it has been dated to the first century AD. The house was built in the centre of ancient Spoletium. In ancient times, the house overlooked the forum, which today is again a large square, complete with a (modern) monumental fountain and comfortable places to sit and have a drink.

The Casa Romana

What has been unearthed of the building so far is roughly square in plan. But the building was originally almost certainly rectangular in shape. While the current remains date from the first century AD, helpful signs in the museum explain that the earliest remains of the building date from the first century BC, when it achieved more or less its final shape.

This house was constructed on an artificial, paved forecourt, about 1.50m beneath the current ground level. The house was built on the cross roads of two of the ancient city’s major roads, the Cardo maximus (modern via dei Duchi and via Arco di Druso) and the cardo decumanus (via dei Municipio, via del Mercato, and via Plinio il Giovane).

The nearby Arch of Drusus served as the Roman city centre’s monumental entrance. The house was located right in the middle of important civic and religious buildings, including a Capitolium and several temples. Someone important must have lived here and, thanks to an inscription, we know who: Vespania Polla, the mother of the Emperor Vespasian (r. AD 69–79). (The museum makes clear that not everyone agrees that Vespania Polla lived here, but for now the attribution stands.)

The house likely remained in use throughout the Roman era and into the early Middle Ages. The museum suggests that it may have burnt down by then. It was partially demolished, since much of the house’s walls were torn down. The remains were discoverd in 1885, after which the house was excavated and consolidated. Since 1991, restoration efforts have been carried out to preserve the mosaic floors and to make the remains visible to the public.

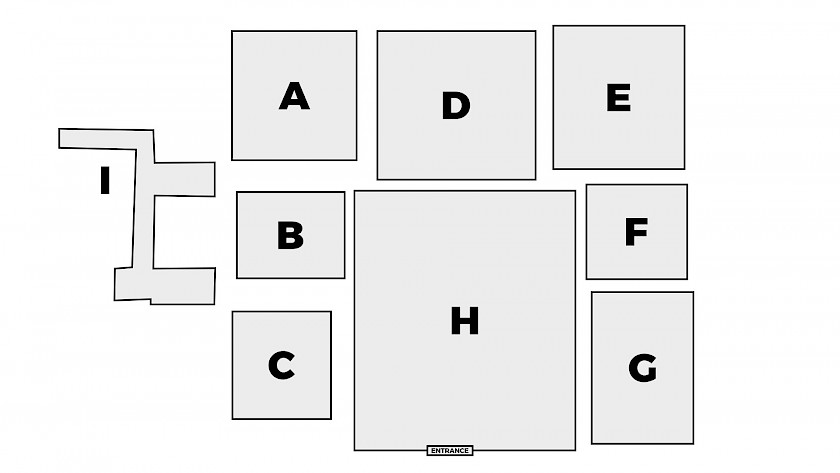

If you visit the building, you have to get in through a small glass door just to the side and down from the town hall. A small room leads to a corridor that opens up to the building’s atrium: the central room around which much of the rest of the house was organized. In the centre is an impluvium: a rectangular pond into which rain water was collected that fell from the opening in the roof (compluvium) directly overhead. This opening provided light and air to this central part of the house.

All rooms that have been excavated are grouped around the atrium. Some of these are cubicula (perhaps bed rooms) or alae (side rooms). An important room is located directly opposite to the entrance. This is the tablinum: essentially the office used by the master (or, indeed, mistress) of the house.

This room was used to receive guests and to conduct business. A patronus would receive his clients in this room, for example. While most of the rooms have black and white mosaic floors, this room also features the use of some red tesserae (perhaps the result of some redecorating in the late first or early second century AD).

Another important room is located directly adjecent to the tablinum. This is the triclinium or dining room. The name, triclinium, derives from the Greek triklinion, which means “three klinai” or “three dining couches”. In other words, this was a room where guests would recline on couches to eat and drink, either within the context of conducting business or just to have a party.

The triclinium also features the best preserved wall frescoes in the entire building, belonging to the so-called Third Pompeian Style (popular until about the mid-first century AD). The wall-paintings consist of a base divided into panels painted to resemble marble, topped with yellow and red squares that are bordered with decorative elements, such as garlands.

Every visitor to the house receives a small booklet with detailed information about the building. There are also a few informative signs. A few small display cases feature some of the smaller objects unearthed in the building, such as pieces of glass, metal, pottery, and bone. It’s well worth seeking out whenever you are in Umbria.