If you’ve ever followed a course on art history, you’re probably familiar with the classical orders. These are different styles of classical architecture as originally used by the ancient Greeks and Romans, most notably in the construction of public buildings like temples. You’ve almost certainly heard someone at some point or another refer to things like Doric temples and Ionic capitals.

In this article, I want to briefly explain what the different classical orders are, how they each differ from one another, and to examine their origins (insofar as there is any evidence to examine). First things first, however, what is an order precisely? John Summerson usefully summarizes it in his little book on classical architecture as follows: “An ‘order’ is the ‘column-and-superstructure’ unit of a temple colonnade” (p. 10).

Different columns

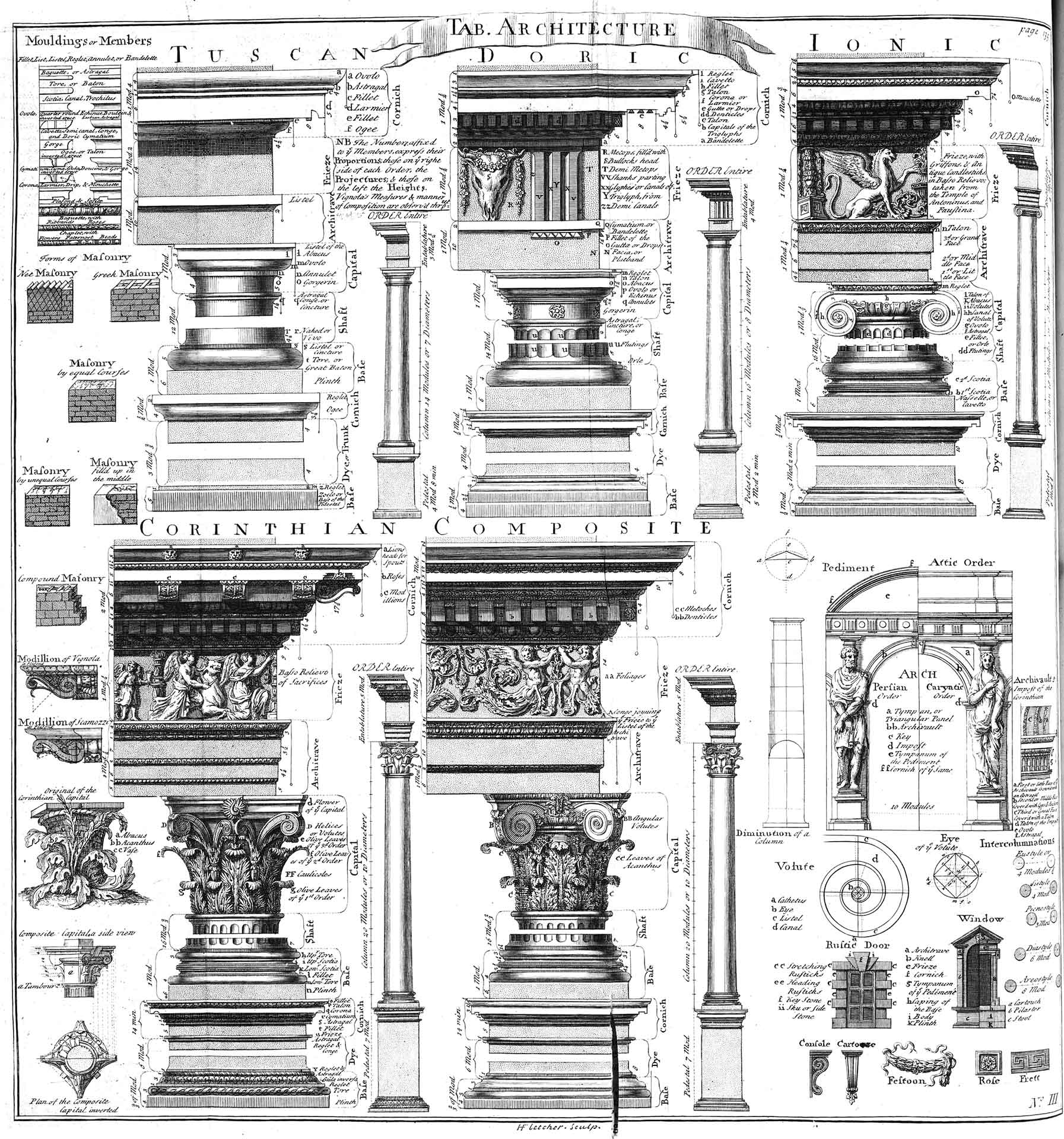

The different styles are most easily recognized by their columns. Three styles were created by the ancient Greeks. These are, in chronological order, the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Two other orders were added later: the simple and elegant Tuscan order and the more ornate “composite” order.

The diagram above is rich in detail, listing all the technical terms that you’d use when describing classical architecture, which includes modern buildings that take inspiration from the ancient world of the Greeks and Romans. Columns consist of a base (optional in some cases!), a shaft, and a capital. The columns support the entablature, which itself consists of the architrave, the frieze, and cornice, and so on.

The Tuscan order is the simplest, with unfluted columns and a frieze that’s left entirely blank. It’s essentially a simpler version of the Doric order. The latter has fluted columns (i.e. with grooves), and the frieze is divided into metopes (panels, often with decoration that is painted and/or set in relief) and triglyphs. A triglyph consists of three bars with channels between them: the idea was once that these were translations in stone of the ends of three planks that once supported the roof, but opinion is divided on whether or not that’s actually the correct interpretation.

Compared to the Doric order, the Ionic order is typically more slender and its capital is more ornate, featuring volutes (curved ends, resembling rams’ horns). The Corinthian order’s most distinguishing feature is its capitals, which feature acanthus leaves. The composite order is essentially a combination of the Corinthian and the Ionic orders, with capitals that marry the Corinthian order’s acanthus leaves with the volutes of the Ionic order, usually set in each of the four corners rather than strcitly bilateral.

Vitrivius and the Renaissance

The earliest source for the classification of classical architecture into distinct orders is De Architectura (“About Architecture”), written by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (ca. 80/70 BC to ca. 15 BC or later). In the third and fourth books of his famous work, he describes the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, and mentions the Tuscan order in passing. He focuses on the origins of the each of the orders and explains for which deities the different orders are most appropriate. Here, for example, is what Vitrivius writes about the origins of the Doric order (4.1.3):

To the forms of their columns are due the names of the three orders, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, of which the Doric was the first to arise, and in early times. For Dorus, the son of Hellen and the nymph Phthia, was king of Achaea and all the Peloponnesus, and he built a fane, which chanced to be of this order, in the precinct of Juno at Argolis, a very ancient city, and subsequently others of the same order in the other cities of Achaea, although the rules of symmetry were not yet in existence.

A truly systematic approach to the classical orders didn’t come about until the Renaissance. In the fifteenth century, Leon Battista Alberti, a native of Florence, described each of the orders based on both Vitrivius and his own investigations of ancient ruins. He added the fifth order, the composite, to the list. A century later, Sebastiano Serlio took Alberti’s work and outlined the henceforth canonical rules regarding the classical orders, idealizing each of them. The Tuscan order is ignored by some modern scholars, who see it strictly as a variation on the Doric order; its status as a separate order is regarded mostly as an expression of nationalism on the part of Renaissance writers.

As you might expect, we shouldn’t therefore be too strict when it comes to applying the classical orders to architecture that dates from ancient times. For example, detailed studies of ancient temples show that ancient architects often experimented with proportions, eschewing the rather rigid schemes devised (or perhaps rather recommended) by writers of the Renaissance (see e.g. the books listed in the further reading). Especially in the Archaic and early Classical periods (ca. 700 tot 450 BC), ancient Greek architects were, of course, entirely free to experiment as they wished.

Ancient origins

Vitrivius claims a mythological origin for the Doric order. However, archaeology has shown that the Doric and Ionic orders both emerged in the seventh century BC, when the first stone temples were built. In the history of art, the seventh century BC in Greece is often referred to as the “Orientalizing” period, as Greek art clearly drew inspiration from the cultures further to the east. In architecture, too, the Greeks were clearly inspired by the stone architecture from Anatolia and further afield, including ancient Egypt.

However, the ancient Greek stone temple does also build on native traditions. Already in the eigthth century, wooden structures were built that were (mostly) rectangular and featured wooden posts or columns, including columns that were positioned between two wall ends (i.e. placed in antis). Of course, the basis structure of the classical orders, with columns supporting an architrave, is nothing less than a variation on the post-and-lintel system, which in the Aegean was already used from the Bronze Age onwards.

The city of Corinth, located strategically on the Isthmus, flourished in the seventh century BC as a result of trade and other overseas contacts. It has been suggested that the earliest stone temples developed here in the seventh century. In Corinth, the dialect spoken was Doric, and hence the style of architecture was referred to as Doric, too. Dorian Greeks were thought to be straightforward; the relatively simple Doric style fit their personality. But lest we read too much into this, the Doric order was also used in regions where the Greeks spoke different dialects, such as in Athens.

The Ionic order was perhaps created in the Greek cities on the coast of Asia Minor, where the Greeks lived in close proximity to powerful Anatolian kingdoms. These Greeks spoke an Ionic dialect, hence the Ionic order. That the Ionic order didn’t spring into being overnight is demonstrated by the existence of a precursor, the so-called Aeolic or Proto-Ionic capital, which features volutes and suggests that the order was inspired by vegatation, or perhaps by palm- or papyrus-shaped columns from ancient Egypt.

Still, the exact place of origin for the Doric and Ionic orders are much debated. Similarly, the earliest evidence for the use of the Corinthian order comes not from Corinth, but from the temple of Apollo at Bassae, in Arcadia, the mountainous region in the heart of the Peloponnese. The Corinthian order is essentially a variation on the Ionic, with the capital its most distinguishing feature. The temple dates from the late fifth century BC. Curiously, however, the Corinthian order was used in this temple for a single column in the interior; the exterior made exclusive use of Ionic columns.

In the fourth century BC, Greek architects experimented with the order, sometimes using one order for columns along the exterior and another for the interior ones. The Lysikrates Monument in Athens, dated to 334 BC, is the earliest example of Corinthian columns used for the exterior. But even so, the Corinthian order was never as popular among the Greeks as the older Doric and Ionic orders. The Romans, however, used the Corinthian order extensively, such as in the Maison Carrée at Nîmes. They also introduced the composite order, which is often considered as nothing more than a variation of the former, created in the first century AD.

Closing remarks

The classical orders developed over the course of the seventh, sixth, and fifth centuries BC. The Greek orders were probably inspired by stone architecture from the ancient Near East, including Egypt, where stone buildings – especially temples – have a history that stretches back hundreds if not thousands of years. The Romans later adopted the architectural forms of the Greeks and added their own innovations, including the composite order, and then spread the tradition across a large swathe of Europe.

The Roman author Vitrivius, an older contemporary of the emperor Augustus (r. 27 BC to AD 14), was the first to write about the classical orders. His work, alongside study of ancient Roman ruins, inspired scholars in the Renaissance, who deliberately sought inspiration from the world of the ancient Greeks and Romans, to systematically develop the classical orders as a model for contemporary architects. The results of their efforts are easily recognized in modern structures such as the British Museum in London, the Glyptothek in Munich, and the United States Capitol.

Further reading

- William R. Biers, The Archaeology of Greece (second edition, 1996).

- J.J. Coulton, Greek Architects at Work. Problems of Structure and Design (1977).

- John Summerson, The Classical Language of Architecture (1963).

- James Whitley, The Archaeology of Ancient Greece (2001).