Last time, we had finished off Elpenor and returned to the Panhellenic sanctuary at Delphi to infiltrate a meeting of the “Cult of Kosmos”, the nefarious cult that is apparently behind everything evil in ancient Greece. As pointed out before, no such cult ever existed in Greece, but the Assassin’s Creed series needs its conspiracies.

After a brief chat with Herodotus, Kassandra puts on a disguise and enters a far-too-conspicuous-looking secret hideout of the Cult of Kosmos. We talk to some Cult members present until finally their hero, Deimos, enters the room. Deimos is revealed to be Kassandra’s long-lost brother and, with the help of magic, he also learns the truth about Kassandra, but hides it from the other cultists. Before leaving, Kassandra grabs a weird, triangular piece of a glowing artefact.

A brief detour

Back out in the open, Herodotus says it’s time to meet Perikles in Athens, but suggests the two of you meet first at Thermopylae. There, Herodotus is found waiting near a giant statue of a lion, which marks the place where Leonidas fell. Herodotus (the real one) mentions a stone lion dedicated to Leonidas and his men (Hdt. 7.225), but it seems unlikely it was as big as the one in the game. The game tends to make statues bigger than normal.

Furthermore, the Spartans who had died here were buried beneath the hill where they had made their last stand. The poet Simonides wrote a famous epigram that was inscribed on a stone plaque (now lost), which read, in the translation of William Lisle Bowles:

Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

As Roel Konijnendijk recently pointed out, the Battle of Thermopylae was a key event that helped shape ancient (and modern!) perceptions of the Spartans as formidable fighters. But it’s worth pointing out that they hadn’t fought the battle on their own. Indeed, Herodotus cites an inscription that acknowledged the sacrifice of the Greek army as a whole (Hdt. 7.228):

Here four thousand from the Peloponnese once fought three million.

In any event, Herodotus joins us on our quest. Before heading to Athens, we have to pass by the island of Andros. It’s funny how the game makes the island seem like a tropical paradise: white sandy beaches and plenty of palm trees. While the Greek islands are definitely beautiful, it at times seems like you’re running around the Caribbean rather than the Aegean! Be that as it may, we have to find our way to an “ancient forge” and use the artefact we recovered earlier to upgrade Leonidas’ spear.

At this point, the game takes us back to the present day. In all honesty, I don’t care at all about the Assassin’s Creed backstory or the struggles between the Assassins and the Templars, nor do I care much about the precursor race (aliens?) that supposedly created/kickstarted (?) human civilization. I play these games because they’re big-budget extravaganzas that allow you to fool around in a particular period of history. So I do what needs to be done and return to ancient Greece as quickly as I can.

Our next stop is the city of Athens.

Trouble in Athens

As mentioned before, distances in the game are much shorter than they are in the real world, so that we cover the distance between Andros and Attica in virtually no time. We arrive at Thorikos, one of Attica’s “demes”, i.e. villages or districts. Some of these demes were significant towns in their own right, such as Eleusis, but subservient to Athens proper.

A quick trip on horseback brings us right into the heart of Athens, with the two most conspicuous features being the Acropolis and the Agora. The Acropolis (Greek for “high city”) is the religious centre of ancient Athens; the Agora serves as its civic centre, with a market and the main public buildings where Athenians engaged in politics.

The Acropolis features all the major Classical structures, including the Propylaea, the Erechtheum, and the Parthenon. The Athenians were able to afford building these grandiose structures on account of the silver extracted from their mines at Laurion and the wealth extracted from the members of the Delian-Attic League, which effectively functioned as an Athenian empire. The Acropolis achieved its familiar form supposedly as the result of an ambitious building program organized by Perikles, Athens’ dominant politician – though our main source for this is the ever unreliable Plutarch (in his Life of Pericles).

The Erechtheum, one of the more curious structures on the Acropolis (about which I’ll write more some other time), wasn’t actually built until the 420s, and wasn’t completed until shortly before the end of the Peloponnesian War, so its inclusion in the game is anachronistic. The synchronization point on the Acropolis is a huge bronze statue of Athena – a statue like this actually existed, except that it was much smaller. if you’re interested, you can read more about this site in Jeffrey Hurwit’s The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present (1999).

Like the Acropolis, the Agora in the game gives a decent idea of what the original may have once looked like. Most of the buildings here seem to be in the correct place. These include various stoai (covered porticos), including what looks like the South Stoa I (which wasn’t actually constructed until the last quarter of the fifth century BC).

The mint is also included, as well as various other public buildings, including the Bouleuterion, which housed the council (boule) of Athens, better known as the Council of 500. Members of the Council were chosen by lot from each of Athens’ ten tribes and served for a year. Each of them were Athenian citizens: that is, men who had both an Athenian mother and an Athenian father.

The year was divided into ten parts, consisting of 35 or 36 days each. The 50 representatives of each of the ten tribes selected for the boule took turns to serve as the council’s executive for one-tenth of the year. These men were called the prytaneis. Their headquarters was the Prytaneion. In Athens, the Tholos, recognizable by its circular ground plan, was used to house the prytaneis. They were fed here at public expense. One third of these men had to be in the Tholos at all times in case of emergencies and so around 17 men even slept there each night.

Among the ancient Greeks, like most ancient peoples, religion was embedded in society. They didn’t even have a word to denote the concept “religion”, as the gods were everywhere. It’s not surprising, then, that the Agora also features religious structures. The most impressive is the Temple of Hephaestus, also referred to as the Hephaesteion or Hephaestium; it was once thought wrongly to be dedicated to the hero Theseus. The temple is today among the best preserved in Greece, thanks to an orthodox church having been housed in it for a long time. Construction started around 449 BC, but the building wasn’t actually completed until 415 BC.

In the game, the Agora is very lively, which seems true to its purpose. There are market stalls, workshops, small shrines and statues, people chatting and gossiping, others talking politics. It’s messy and noisy and it feels quite authentic. For more information, the best place to start is John M. Camp’s The Athenian Agora: Excavations in the Heart of Classical Athens (updated edition, 1992). There’s also an extensive website about the Agora excavations.

For the purpose of the game’s plot, we have to meet Perikles at the Pnyx. The Pnyx is a rocky hill in the centre of Athens, where the popular assembly or ekklesia gathered. This is where Athens’ politicians sought to sway public opinion to their cause. It’s fitting, then, that we arrive at the Pnyx right when Perikles and his major rival, Kleon, are debating.

Perikles appears as a goodly old man, while Kleon is clearly up to something. The developers here have followed the original sources, for better or worse: both the historian Thucydides and the comedic playwright Arisophanes appear to have loathed Kleon, depicting him as a warmongering demagogue.

Perikles wishes to invite us to a symposium, but we need to accomplish a few tasks first. One of them is to doctor the results of an ostracism. In Athens, ostracism was used to exile someone who was deemed a threat to democracy, by carving his name into sherds (i.e. ostraka). Roel Konijnendijk pointed out to me that the Athenians didn’t engage in ostracism between 441 and 416, and that Hyperbolus’ ostracism in 416 BC is actually the last time the practice was used.

Another task sees us escort Phidias to safety. The developers followed Plutarch here in presenting Phidias as the architect tasked with carrying out Perikles’ building program; in reality, Phidias had been accused of embezzlement in 438/437 BC and had fled the city, so well before Kassandra ever set foot in Attica.

Still, the mission where we have to safeguard Phidias takes us to the Piraeus, Athens’ harbour town. Since in the game the geography is bunched together, Piraeus appears more like a suburb of Athens, without a clean break visible between one or the other. In reality, the two were connected using the Long Walls by the time of the Peloponnesian War. These Long Walls ensured that Athens could withstand a siege, while supplies were shipped in via the sea. Athens’ fleet was without rival, so no hostile power would have been able to effectively blockade the harbour. An interesting detail in the game is the inclusion of ship sheds, which were used to store Athens’ triremes when not in use.

When all tasks are done, we head to Perikles’ rather luxurious house in Athens. We are greeted by Aspasia, Perikles’ mistress. Originally from Miletus, an important city in Asia Minor, little is actually known about her for sure. Athenian intellectuals, including Socrates, Plato, and Xenophon, were entertained at her house, and she’s shown in the game as hosting the party that Kassandra’s been invited to attend. Some ancient sources claimed she was a hetaira, a well-educated, high-class prostitute or courtesan (often contrasted with pornai, the less well regarded prostitutes); but there are reasons to doubt this.

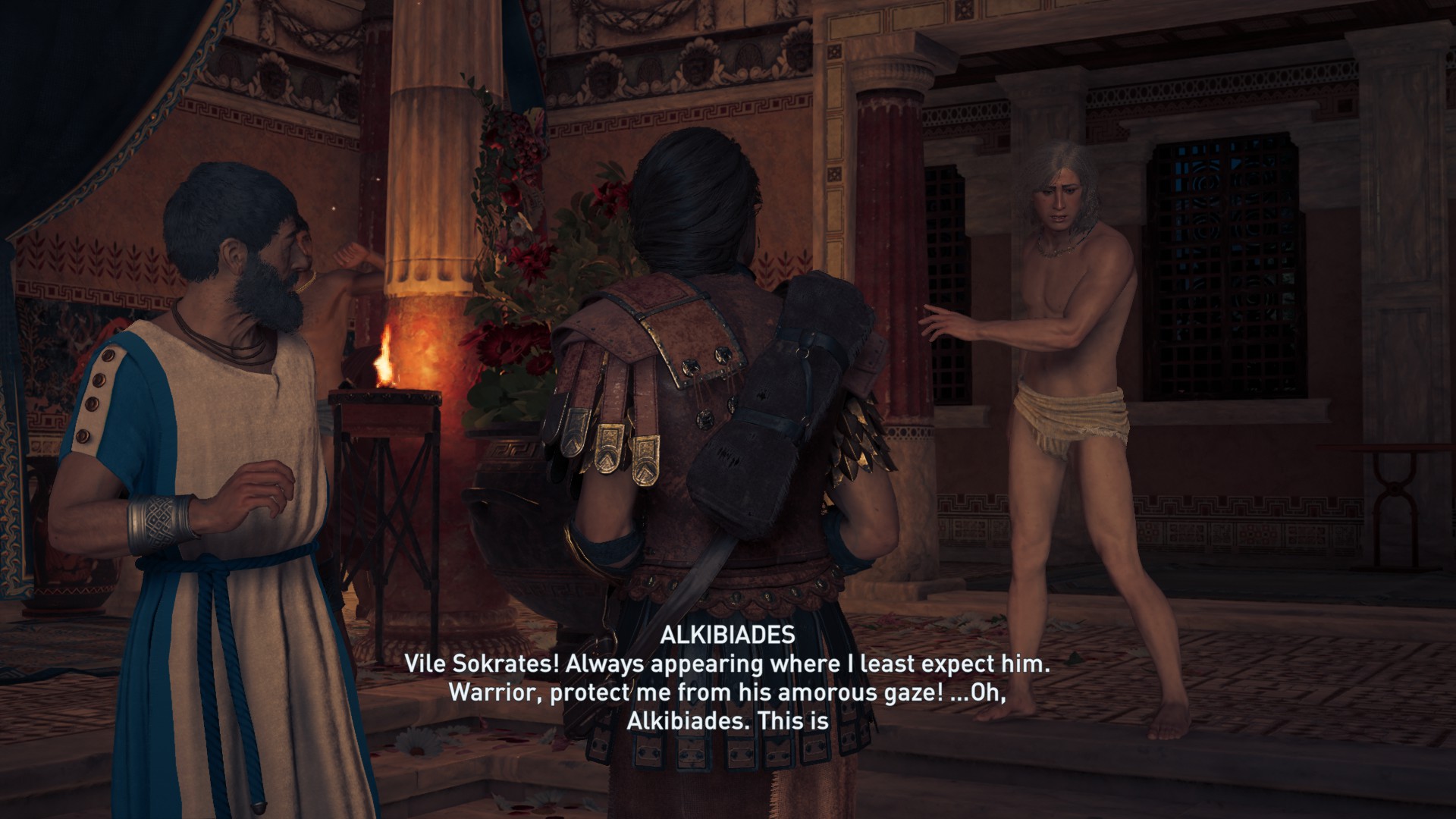

At the symposium, we engage with a wide range of other famous people, including the philosopher Socrates (whom we actually met earlier at the bouleuterion) and the playwrights Euripides, Sophokles, and Aristophanes. We also meet the colourful Alkibiades, about whom I’ve written in greater detail before. At the end of the evening, Kassandra has acquired a number of leads that will aid her in completing the various plot lines that the game has thrown out and which are scattered all over Greece and the Aegean.

Closing thoughts

This is a good point to end my detailed survey of the game. I’m nowhere near done, but the major elements of the game’s plot are now laid bare: Kassandra needs to find her parents and reconcile with her brother. At the same time, she needs to take down the evil Cult of Kosmos, who is responsible for her family’s misfortunes. The dubious Kleon is clearly a central character in that plot line.

There’s little point, I think, in continuing to write a commentary about the game since I’ll start to repeat myself: for example, much of what I wrote about Delphi also applies to the game’s depiction of the sanctuary at Epidaurus, one of the places that I visited after my stay in Athens. In general, the developers have done a decent job. There are, of course, lots of mistakes, but all things considered this is not a bad attempt at capturing the look and feel of Classical Greece. If someone plays the game and becomes interested in ancient Greece as a result, that’s all the better.

Still, this is not the final part in this series on Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey. I’ll write one more article to wrap things up and will include comments on the three books that are connected to the game: the novelization, the Art of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey book, and the Prima Guide.