When you think of the ancient Etruscans, you probably picture them living in what is today Tuscany, a region on the western coast of central Italy, just north of Lazio (ancient Latium). But they also lived in, and interacted with, a wider part of the Italian peninsula. They settled towns in Campania, to the south (the area now dominated by Naples), as well as in the Po River Valley, with important settlements in the area of modern Bologna. They also founded a number of cities in what is now Umbria.

In an earlier article, I touched upon the Etruscan necropolis in Orvieto. The archaeological museum there has a collection of objects from Etruscan tombs. However, it pales in comparison to the massive collection of Etruscan objects on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria in the regions’s capital city of Perugia.

The museum is a bit hidden away, located below the upper town of Perugia, with the entrance right next to the San Domenico church. Since 1948, the museum has been housed in the former complex of the Domenican convent. The entrance opens up into a courtyard with peristyle. The walls here are lined with dozens upon dozens of artefacts, most notably a large number of Etruscan cinerary urns.

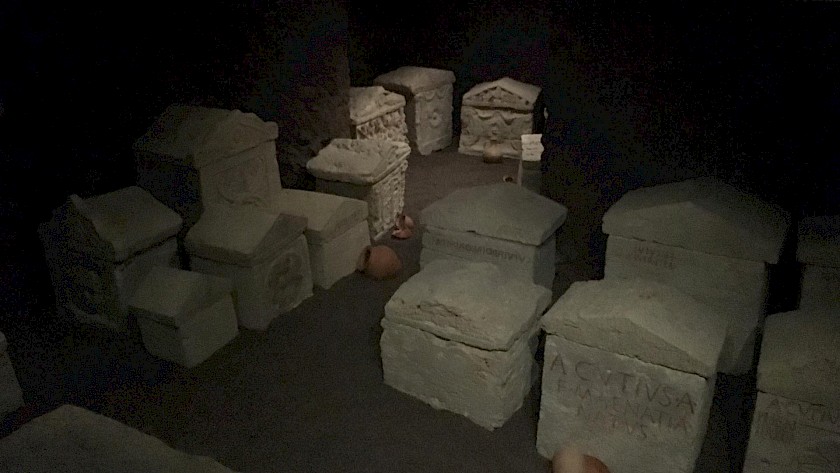

These urns tend to be fairly small and made from (local) stone. Most of them date from the first two centuries before the common era. The urns were originally buried in tombs. The museum features an underground chamber with a reconstruction of the so-called Cai Cutu Tomb, unearthed in 1983 and named after the descent group that it belonged to. This tomb was in use from the third century to first century BC; the reconstruction offers an excellent look at what it may have originally looked like.

Etruscan urns generally feature scenes inspired by stories known from Greek mythology. A point made before on this website is that the Etruscans who made and used these scenes may or may not have regarded them as typically “Greek” (i.e. foreign): they had no doubt made the stories their own, incorporating them within their own culture, in the same way that today, for example, people outside of the United States have embraced Star Trek and made it part of their own identity.

The museum also houses a large collection of Etruscan bronzes from San Mariano. These are housed in a small room on the first floor in which signs provide a considerable amount of information about the excavations, which date back to 1812. The most notable objects on display here are a large number of pieces of decorative bronze metalwork, dated to the sixth century BC, many of which were once fixed to (two-wheeled) carts.

As with the cinerary urns, a lot of figurative scenes on these bronze pieces depict figures known from mythology. A large flat piece from a cart depicts a gorgon (perhaps even Medusa herself, known from the story of her death at the hands of Perseus), while another pieces depicts the Minotaur, who was slain by the hero Theseus.

The National Archaeological Museum is a lot bigger than you would at first expect. The ground floor largely consists of just the peristyle and an additional room. The first floor, however, is much larger and features a large number of additional rooms, including a massive hall that showcases objects made by both the Etruscans and the local Umbrians.

Aside from the Etruscan objects, the museum houses Roman artefacts, including a number of sarcophagi, and includes a collection of prehistorical and protohistorical objects, a large number of coins, rooms dedicated to amulets and jewellery, as well as tempoerary exhibitions. We visited the museum in the afternoon and basically ran out of time, having to rush through the last few rooms.

So here’s my tip for you: if you’re in Perugia, you really need to visit this museum, but make sure you do this as soon as possible. When you’re done here, you can go to the upper town and relax with a cool drink on one of the city’s many excellent terraces.